He was one of the more remarkable characters I have crossed paths with in my lifetime: Lee Arbuckle ’65 of Alzada, Montana, Peace Corps volunteer, rancher, writer and philosopher, inventor and, finally, subject in an experimental drug trial to combat cancer.

I learned of his death the same day I returned from the funeral of a local service club friend of 30 years—a most sobering day.

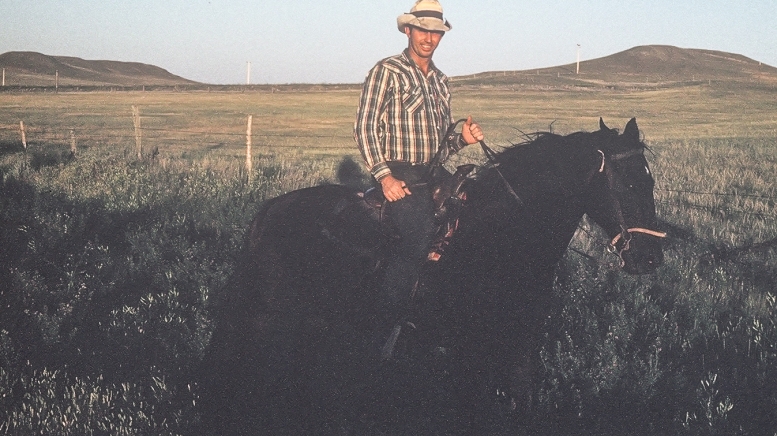

I would describe Lee as tall, lanky, a bit rough-hewn, accented when I first met him by a gold-rimmed front tooth, a gravelly voice and a warm, friendly personality. Yet, as he was fond of saying, with a chuckle, “I went to a country school so small that I was the best-looking guy in my class.”

I met Lee in the fall of 1961 when we matriculated at Dartmouth. Both of us, however, dropped out after two years, he to join the Peace Corps as a small business advisor in Colombia, I to join the U.S. Army as a member of NATO forces in France. Both of us returned to Dartmouth after our three-year “sabbaticals” to get our degrees. I often ran into him in the Hopkins Center cafeteria or in the College dining hall. If I remember correctly, it was he who announced to us at the latter site that Robert Kennedy had been assassinated.

Following graduation in 1968 I made a solo camping trip around the United States. One of my destinations was that Alzada cattle ranch, welcomed by a large replica of the Arbuckle brand on the archway above the main entrance.

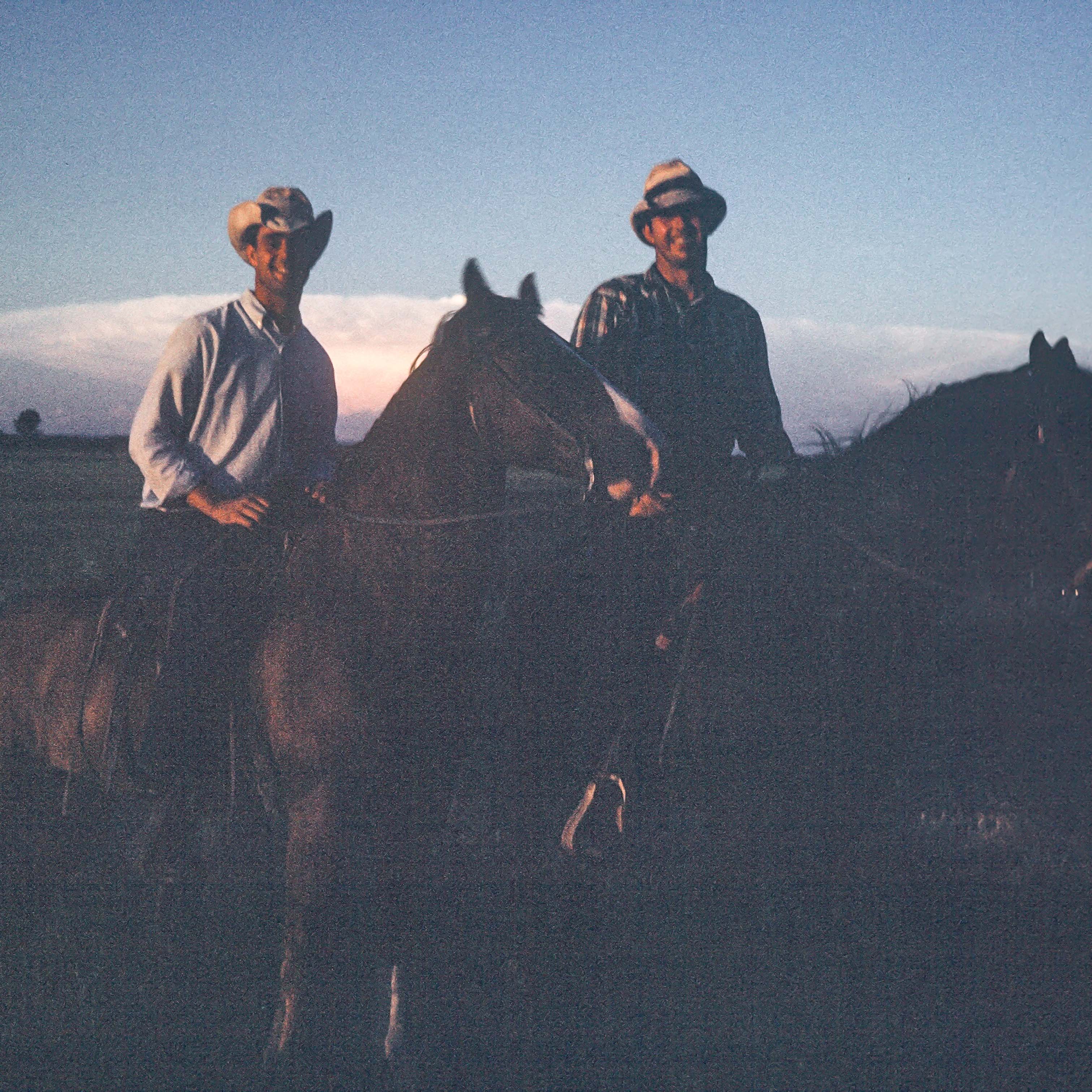

My first night at the ranch we literally rode off into the sunset on a tour of the land. We rode across grasslands, through trees and along a streambed. I have a photograph of the evening—a bit underexposed—that captures the experience. The next day we rode out in search of an escaped bull. My classmate a natural, me bouncing in the saddle like a greenhorn as the horse broke into a gallop.

Years later, after he had visited Massachusetts and we had gone out to dinner, I sent Lee a copy of the old photograph.

“Great photo from yesteryear,” he wrote back. “You ‘sit’ that sorrel horse well. Horse’s name was Sailor. Good cow horse. Had a lot of sense for working cattle and a lot of heart for working.

“Counting on you coming out to Montana again,” he concluded, “and we’ll go to the ranch. Sailor is long gone.”

While I never did get back, my younger son stopped at the ranch some 30 years later, on his own camping trip around the country, to replicate the photograph from his father’s visit, and I saw Lee on a number of occasions when he passed through Massachusetts. I also saw him at our 50th College reunion in 2015, which I attended to see him and two others who had been my roommates.

On the latter occasion we walked across the campus, he with a cane due to long-term complications of multiple sclerosis, to see the Orozco frescoes in Baker Library. There, he startled a young male Hispanic visitor on tour with his mother by transitioning into fluent Spanish to discuss the meaning of the murals, the advance of Western “civilization” into the Americas.

In the meantime, although the multiple sclerosis forced him out of active management of the ranch, Lee pursued the patenting of a seed harvester designed for prairie grasses that, he observed, a common combine harvests poorly or not at all.

Not long thereafter he revealed that a case of once-thought-cured throat cancer had metastasized into his right lung with a six- to18-month life expectancy, a journey he described as “paddling my canoe forward into the actuarial tables.”

“Needless to say,” he admitted, “that captured my attention.” What followed was gratitude for an interesting life, acceptance that sooner or later a “stranger” would be tapping him on the shoulder and, finally, a determination to “fight my darnedest to spit in the eye of this particular stranger.”

The fight took him from Montana to Houston and into a network of doctors that was experimenting with an immunotherapy drug, Nivolumab, plus a vaccine that hyperstimulates the immune system to produce T-cells that attack the cancer.

“As someone who walked over one grassy hill and another to get to Dartmouth,” he said, “I’m expecting I will be among participants with the best outcomes.”

That, alas, was not to be, and he eventually moved onto other trial protocols, saying, “It is important that this time I turn over a high card, as my options are narrowing.” That, too, was not to be. Initial optimism each time was followed by eventual disappointment.

All along the way he acknowledged the support of his wife, Maggie, whom he had met in Bolivia. “By the day, I give thanks that I was paying attention when she first walked by.”

So, too, was Lee grateful for two sons, one of whom visited near the end: “the sort of visiting when no one is attempting to stuff silence full of words. Good pacing, like a 1950s Frank Sinatra ballad.”

Doing it his way meant a life of adventure, curiosity, anticipation, dedication, achievement, optimism and good humor.

I am privileged to have called him a friend.

Stuart Deane is a columnist for the Newburyport (Massachusetts) Daily News and a previous contributor to DAM. He lives in Newburyport.