“I’m Going to Kill Myself”

My college experience wasn’t just about football. And in some ways, I was hurting too. I set out to wrestle during my freshman winter term but quit after one match. Blame it on the beast that was the academic challenge greeting a premed major. Even though I scored mid-eighties on tests, that was C or D work. The competition was so high.

I finished my first term with all Cs. I’d never worked harder academically. If I continued with my whole courseload, I could probably get Cs and Bs, but that wouldn’t be competitive enough to get me into medical school. I was unable to wrestle and do better academically. I had to give one up. I had to quit wrestling. Then I got sick and couldn’t sleep. On the whole campus, there was not another light on anywhere as far as I could see—and that insomnia put me even further behind the curve academically.

That’s when I said, in the middle of the night, “I’ve got to give up. I’m going to kill myself.”

It was a sad option to consider, reflective of my despair. I was so depressed that I was going to let my father down that I thought of jumping out the window. Well, it was winter time, and I was on the second floor of the dormitory. The snow was so deep that if I jumped, there was no way the plunge would kill me. So I decided to jump off the bridge spanning the Connecticut River between Vermont and New Hampshire. I sprinted from my dormitory, straight down Wheelock Street, down a hill, and I was flying. Flying and crying. I was about to end it all. And it started to feel so good. I’d never run as fast. As I got close to the bridge, I figured I’d kill myself on the way back. I ran across the bridge to the “Norwich” sign and ran back. My reasons for killing myself were gone. But my reasons for continuing to do this late-night running were on. So, I changed my whole preparation. The next term, I changed all my morning classes to the afternoon so that I could run every single night. I didn’t run that first football season, and I didn’t run during wrestling season, but every other term I was at Dartmouth, I ran at two o’clock in the morning, like two and a half miles roundtrip. I’d run from whatever dormitory I lived in, and I’d hit that sign at Norwich. And my conditioning was always superior to anyone else’s. That was one of my secret ingredients—one of the lessons I taught myself for turning a negative into a positive.

Thankfully, I overcame that personal crisis. Changing my major to psychology helped. Another factor came during spring term: I pledged a fraternity. The Theta Zeta Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha had just been organized on campus after seven students—including Ron and Don Smith, identical twins from Seattle and bookend cornerbacks on the football team—went to Boston College every weekend for a year to earn the charter for the first African-American fraternity at Dartmouth. I was part of the first pledge class.

Dartmouth had, even to its detriment, a traditionally dominating fraternity culture. It was the inspiration for National Lampoon’s Animal House, the classic movie cowritten by Dartmouth grad Chris Miller, based partially on his experiences with Alpha Delta Phi and their zany frat house environment. The Alpha Phi Alphas, founded at Cornell in 1906, didn’t have a house at Dartmouth, but we had an ideal standard that we wanted for all African-American students to survive in a competitive Ivy League environment.

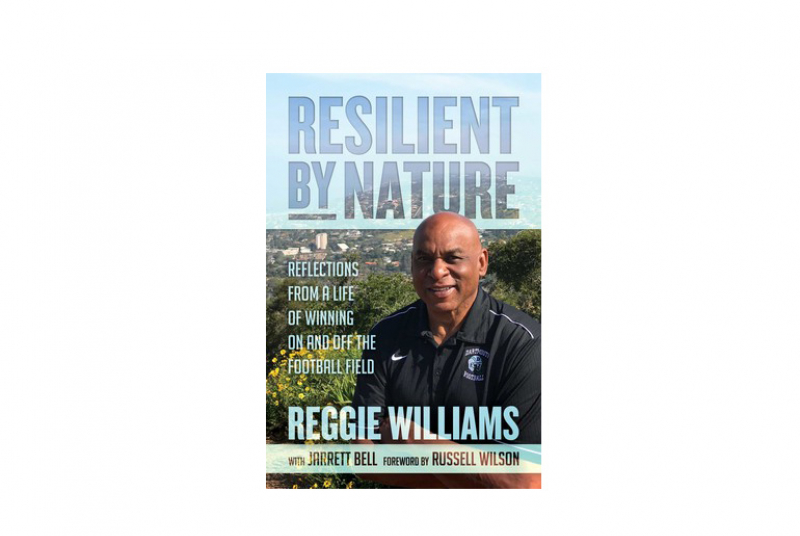

Excerpted from Resilient by Nature (2020) with permission of the author.