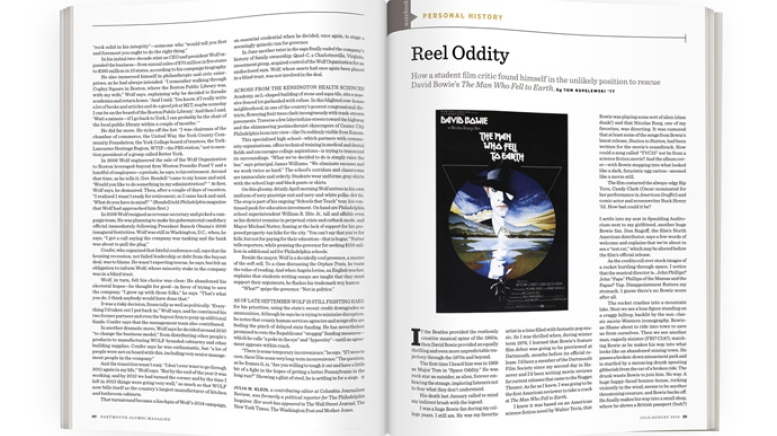

If the Beatles provided the restlessly creative musical spine of the 1960s, then David Bowie provided an equally thrilling and even more unpredictable trajectory through the 1970s and beyond.

The first time I heard him was in 1969 as Major Tom in “Space Oddity.” He was rock star as outsider, as alien, forever embracing the strange, imploring listeners not to fear what they don’t understand.

His death last January called to mind my indirect brush with the legend.

I was a huge Bowie fan during my college years. I still am. He was my favorite artist in a time filled with fantastic pop music. So I was thrilled when, during winter term 1976, I learned that Bowie’s feature film debut was going to be previewed at Dartmouth, months before its official release. I’d been a member of the Dartmouth Film Society since my second day in Hanover and I’d been writing movie reviews for current releases that came to the Nugget Theater. As far as I knew, I was going to be the first American reviewer to take a crack at The Man Who Fell to Earth.

I knew it was based on an American science fiction novel by Walter Tevis, that Bowie was playing some sort of alien (slam dunk!) and that Nicolas Roeg, one of my favorites, was directing. It was rumored that at least some of the songs from Bowie’s latest release, Station to Station, had been written for the movie’s soundtrack. How could a song called “TVC15” not be from a science fiction movie? And the album cover—with Bowie stepping into what looked like a dark, futuristic egg carton—seemed like a movie still.

The film costarred the always-edgy Rip Torn, Candy Clark (Oscar-nominated for her performance in American Graffiti) and comic actor and screenwriter Buck Henry ’52. How bad could it be?

I settle into my seat in Spaulding Auditorium next to my girlfriend, another huge Bowie fan. Don Rugoff, the film’s North American distributor, says a few words of welcome and explains that we’re about to see a “test cut,” which may be altered before the film’s official release.

As the credits roll over stock images of a rocket hurtling through space, I notice that the musical director is…John Phillips? John “Papa” Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas? Yup. Disappointment flutters my stomach. I guess there’s no Bowie score after all.

The rocket crashes into a mountain lake. Next we see a lone figure standing on a craggy hilltop, backlit by the sun: classic movie-Western iconography. Bowie-as-Shane about to ride into town to save us from ourselves. Then we see another man, vaguely sinister (FBI? CIA?), watching Bowie as he makes his way into what looks like an abandoned mining town. He passes a broken-down amusement park and is startled by a menacing drunk spouting gibberish from the car of a broken ride. The drunk wants Bowie to join him. No way. A huge happy-faced bounce-house, rocking violently in the wind, seems to be another threatening creature, and Bowie backs off. He finally makes his way into a small shop, where he shows a British passport (huh?) and we learn his name is Thomas Jerome Newton. He sells a gold ring to the ancient Native American proprietress. He says it’s from his wife. As the Native woman opens the cash register, we see a handgun inside. Just who’s threatening whom? Welcome to America.

Bowie approaches a river and scoops some water into a tin cup. He sits and drinks. He pulls a thick roll of $100 bills from his pocket and begins to count. But wait: Didn’t he just sell a ring for 20 bucks? Okay—maybe time has passed. Maybe lots of time, even though Bowie’s still dressed in the same clothes he had on in the previous scene. Roeg is disorienting us from the outset. It wouldn’t be the first time.

Now we’re in New York City, in an upscale penthouse. Buck Henry is adjusting the volume on the stereo, so this must be his place. Bowie is ushered inside, dressed nattily in a black suit and wide-brimmed hat. We learn that Henry is a patent lawyer named Farnsworth. Bowie shows him a folder that contains nine patents. A stunned Farnsworth tells him, “You can take RCA, Eastman Kodak and DuPont for starters. In three years you’ll be worth $300 million.”

“I need more,” says Bowie.

Suddenly we’re no longer in a Western. This is film noir territory, and Bowie is the femme fatale with a stash of cash and a mysterious agenda. Nothing wrong with a little genre-hopping. But what exactly is this movie supposed to be? There are moments of humor and satirical music cues. And lots of sex, lots of time spent with side characters in scenes that seem barely connected to the story. The story seems to take place across 30 or 40 years, but Bowie never ages a day. We eventually realize he must be immortal.

About the only aspect of the film the viewer could hold onto was Bowie’s touching relationship with Mary Lou, the naïve hotel chambermaid played by Clark, with whom Newton is drawn into increasingly dangerous games of sex and violence. When his loneliness leads him to reveal his true alien self to her—hairless, genderless, cat-eyed, completely vulnerable—Mary Lou freaks out. The audience should react with shock, then with sympathy. But Clark’s reaction is so over the top (there’s even a close up of her legs as she pees herself) the Dartmouth audience roared with laughter.

I had wanted The Man Who Fell to Earth to be great. Now I was realizing it probably wasn’t even good. I was hoping for some miraculous recovery, but the audience had already made up its mind. They hated it.

That night I struggled to write my review for The Dartmouth. I talked about Roeg’s arresting editing style, fantastic imagery and offbeat casting. I talked about the themes—of what it means to be an alien in America and of Newton’s “fall” to Earth, helpless against the decadent gravity of modern American consumer society. I described the film as “unique and challenging,” “thematically rich and complex” with “a winning performance by Bowie.” I also said that it was “often self-indulgent” and “certainly has its flaws.” The D published it with the headline, “New Roeg Film is Most Elusive.”

Two days later Blair Watson, the congenial ex-military pilot who, along with screenwriter Maurice Rapf ’35, had overseen the Dartmouth Film Society since 1949, told me that Rugoff wanted to schedule a phone call with me. “Why?” I asked. “To fix that film,” Watson told me.

Rugoff had paid $800,000 for the North American rights to The Man Who Fell to Earth, the most he’d paid in his career. After the disastrous preview, he was convinced the film, at two hours and 20 minutes, was at the very least too long. Rugoff was no bottom-line hack. He was a tastemaker and trendsetter—and he trusted the Dartmouth audience. The year before he had previewed Monty Python and the Holy Grail, which we had loved and which had gone on to be a huge hit, particularly with the college market.

Rugoff had been impressed with my review. Now he was anxious to hear any thoughts I might have on cuts that could help the film connect with an audience. For as long as I could remember, I had been spouting off about films and what I would have done to make them better. Here was my chance to put someone else’s money where my mouth was, but this was highly uncomfortable. I was being asked to interfere with the work of a filmmaker whom I admired and respected. It felt like sacrilege. On the other hand, I wanted Bowie’s film debut to be a hit. Here was my chance to help.

When the call came through, I could hear the desperation in Rugoff’s voice: He appreciated my attempt to make sense of The Man Who Fell to Earth, but the film was a mess, wasn’t it? I couldn’t bring myself to say those words, but I had to admit it could be improved. Rugoff seemed to be hung up on the many nude scenes. They hadn’t bothered me so much, but even I didn’t really see that a shot of Rip Torn’s penis added much to the cinematic experience.

We also talked about Clark’s performance, which we agreed was a highlight of the film despite histrionics that lost the audience, especially during that alien-reveal scene. I felt a little judicious editing could help her. Rugoff insisted that the pee-down-the-leg shot had to go. He also deleted a sex scene in which Clark and Bowie roll around naked on a bed playing with a loaded handgun. (I had liked that one.) I suggested losing some of the driving shots of various characters traveling across the barren Southwest. I also suggested losing a long sequence in which Bernie Casey—as a mysterious agent who orchestrates the kidnapping of Newton just before he’s about to travel in his self-financed rocket ship back to save his home planet—has an interlude with his wife and ponders existential questions. Why did we need this scene? Bernie’s the bad guy!

In the end, Rugoff edited about 20 minutes from the film, but I wasn’t sure it was ever going to be coherent. The Man Who Fell to Earth was released in May 1976 to mixed-to-negative reviews. Roger Ebert wrote in The Chicago Sun-Times: “Here’s a film so preposterous and posturing, so filled with gaps of logic and continuity, that if it weren’t so solemn there’d be the temptation to laugh aloud.”

Little did he know that the Dartmouth audience had been there, done that. Ebert also went on to wonder, as many critics did, whether the original, longer cut of the film worked better. It was a natural suspicion, especially after word got out that Rugoff had taken the film away from Roeg and had cut it himself “after taking advice from a psychiatry professor and some college students” (or so wrote Graham Fuller, for the Criterion Collection’s 2006 DVD release of the film).

No matter. The film was a critical and financial bust on its initial release. Bowie claimed in the press that he had never read the script, and that his memories of the shoot were hazy due to Herculean cocaine consumption. Roeg offered the playfully perverse theory that Thomas Jerome Newton isn’t really an extraterrestrial at all and that the entire film may be the fever dream of an entrepreneurial British genius who gets lost in America and descends into paranoia, alcoholism and madness. That may just track.

Since then Rugoff’s bastardized cut of The Man Who Fell to Earth has pretty much disappeared—the original “director’s cut” is the only version available on DVD—but critical reassessment has become kinder. The film gets an 83-percent “Fresh” rating from critics on the Rotten Tomatoes site and a so-so audience rating of 70 percent. Joshua Rothkopf in Time Out called it “the most intellectually provocative genre film of the 1970s,” although I’ve never met anybody who truly enjoys sitting through it.

Looking at the film 40 years later, I still find it infuriating and often mesmerizing. Numerous images have stuck with me. There was something there worth saving, wasn’t there?

Apparently Bowie thought so, too. Before his death from liver cancer he collaborated with Irish playwright Enda Walsh on a stage musical called Lazarus, which revisits his Thomas Jerome Newton character. It features four new Bowie songs as well as older choice cuts. During its short run it was the hottest ticket in New York City after Hamilton, but I have yet to read a critic who has been able to make sense of the plot—which somehow seems about right.

Tom Ropelewski, a former student director of the Dartmouth Film Society, is a screenwriter and director known for films including Madhouse, Loverboy and the award-winning 2015 documentary, 2e: Twice Exceptional. He lives in Berkeley, California.