Spice of Life

For as long as I’ve read books, I’ve read menus. I remember taking breaks from homework to peruse restaurant websites, seeing dishes and flavors I had never heard of, and wondering what they might taste like: Pupusas. Ponzu. Chicken-fried steak.

I grew up in Dallas—a city that, at the time, was a magnet for chain restaurants. Our idea of a fancy night out was Olive Garden. (I still can’t resist the toasted ravioli.) But Dallas is also one of the biggest travel hubs in the world, and my mom worked in the airline industry. It was travel that helped me realize just how much food can teach you about the world.

My mom’s job meant our family could sometimes fly at a steep discount. We would pack our bags for climates of all kinds and test our luck at the airport. Sometimes we’d spend all day there and be rewarded with four seats to Paris. Other times, our trip ended at the terminal. I was fortunate to visit Egypt, China, Japan, Morocco, Peru, and Greece before I graduated from high school—and even more fortunate to sample all these countries’ foods.

I became mesmerized by the intricate process of lamination that goes into making a croissant at a Paris bakery. I chowed down on kiwicha, a porridge made with amaranth, to fuel up for fishing excursions in the Amazon jungle. I learned the hard way what happens when you ask a ramen chef in Tokyo to douse your broth with chili sauce.

My mom and I returned from these trips buzzing about all the dishes we had tried, eager to recreate them in our kitchen. We researched online, spoke to friends whose families were from these various countries, and eventually cooked our own versions of the meals. Having hummus from Egypt, spanakopita from Greece, and tagine from Morocco at home was magical and transportive.

I also discovered that many cuisines of the world didn’t exist solely in my kitchen recreations—they also could be found in the Dallas suburbs, if you knew where to look. My dad and I took pleasure in ogling the vast noodle selection at H-Mart, a Korean grocery store. I savored the tamales that my classmate Andres’ grandmother used to send with him to our Spanish class.

By the time I turned 10, I was reading cookbooks and restaurant menus. But cookbooks for my age group felt homogeneous. I didn’t want to learn to make turkey roll-ups and mini pizzas. The kids on the cover of many of these books never looked like me. I loved some of the recipes, but many of the diverse flavors that had gotten me so excited about food in the first place were missing.

The memory of cookbooks and food magazines that didn’t feel like they were written for me sticks with me to this day. When I moved to New York City, known for its vast ethnic diversity, I found very few brown people writing cookbooks or food magazine features. That’s why I’ve devoted my career to ensuring different kinds of people feel seen and heard when they read my stories and cook my recipes.

After I got my first food-writing gig—a column in The Dartmouth about designing your own dining hall meals—I felt empowered that someone like me could be an authority on food, even if only for 300 words. My first cookbook, which I published just after I graduated, was called Ultimate Dining Hall Hacks. It showed students how they could transform ingredients from their dining hall into Thai-inspired peanut chicken wraps or a banana crumble.

My cookbooks have always been reflections of periods in my life. I wrote Ultimate Dining Hall Hacks for my college self, then Indian-ish to celebrate the Indian American food I grew up with and my journey to embracing my identity.

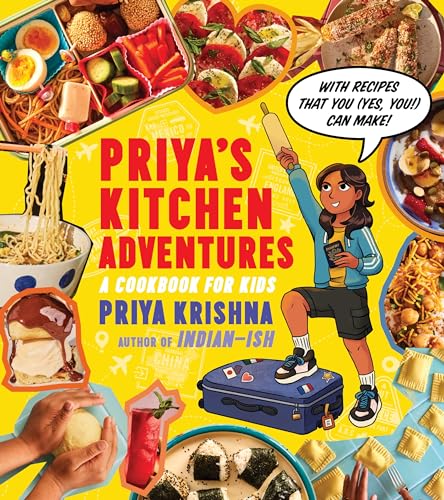

For my next book, I wanted to write about my childhood. I remembered my little self, traveling the world both literally and from our kitchen. I flipped through the journals I had kept from those trips and realized I had documented in great detail all the foods I had eaten. There were enough dishes in these journals to fill a cookbook—the one I had desperately wanted as a 10-year-old.

The book, Priya’s Kitchen Adventures, shows kids they can travel around the world just by eating. It’s a travelogue-meets-cookbook, with recipes designed for little hands. I didn’t tone down the flavors because I believe kids are more open to trying new things than we give them credit for. I worked with 30 kid recipe testers, most of them from my nieces’ and nephews’ schools. One kid told me that he thought he didn’t like fish sauce until he tried it inside a dumpling. Another wasn’t a fan of squash but loved it atop a tostada. One had blunt feedback about a soup recipe: “Yucky.” (I cut the dish from the book.)

Today’s kids are growing up in a more expansive and diverse environment than I did. Yet cookbooks for them have not changed much. Many of our assumptions about food are shaped during childhood. Think about the foods you find most

comforting—they’re probably ones you grew up eating from a young age. By teaching kids about different cuisines, my hope is they’ll grow up to be just as nostalgic for onigiri, profiteroles, and dumplings.

Priya Krishna, a food reporter and video host for The New York Times, is the bestselling author of several cookbooks. She was named to Forbes’ "30 Under 30" list in 2021.