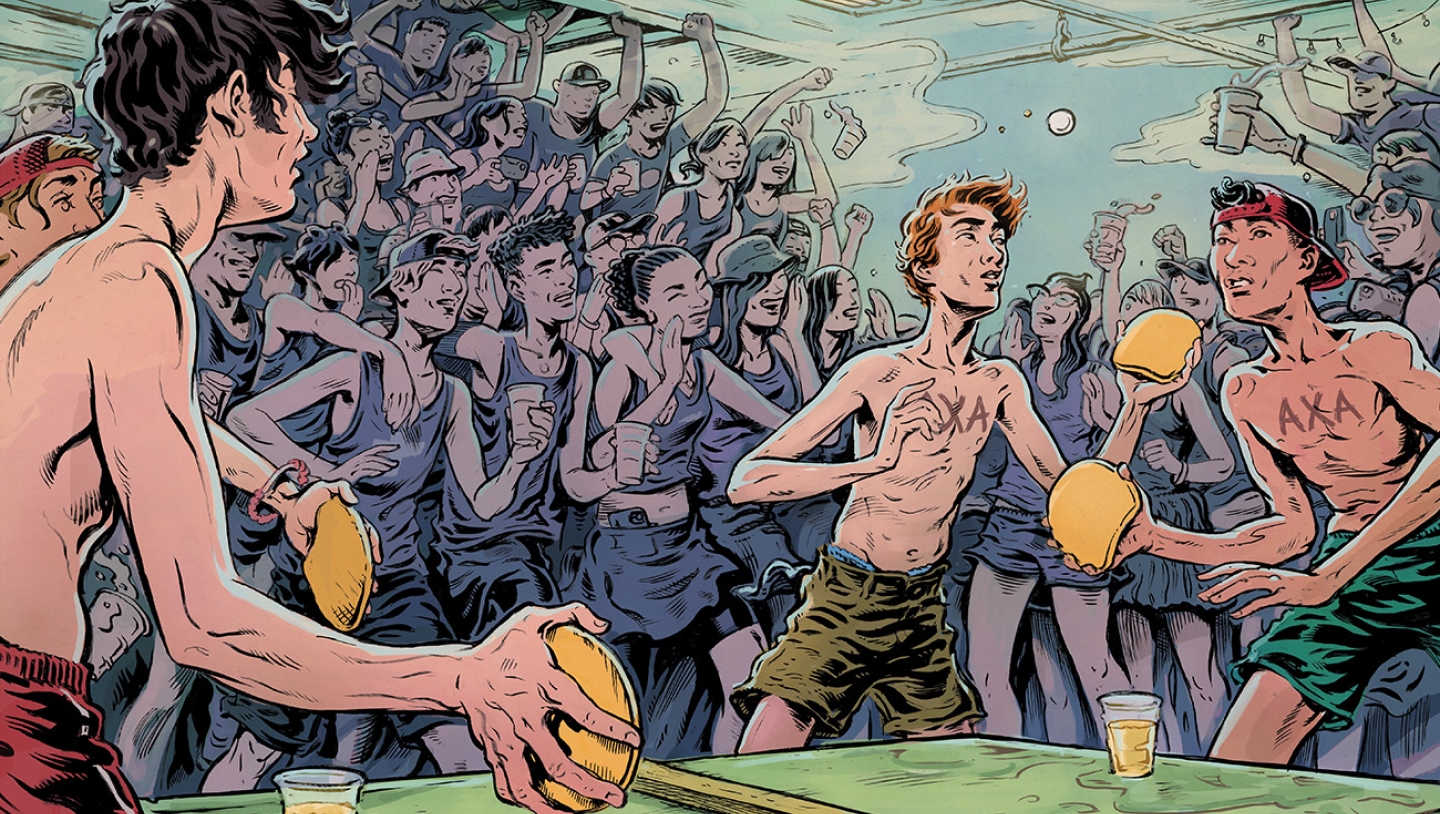

He’s not all right. The shirtless boy is unsteady.

Someone grabs a trash can. A cluster of bodies siphons off and the boy stumbles over to the can, grabs the rim with one hand, and shoves his other deep into his mouth. A hot stream of vomit falls down his fingers and into the can. It’s

amber-colored and watery. The boys around him are jovial, some of them laughing. His teammate, wearing all white, smiles. He puts a fist up and cheers.

Today is the annual Masters tournament. It’s August of my Sophomore Summer, 2022. Two teams each from 12 fraternities are competing in games of beer pong to be crowned champions.

“This is the best day of the year,” I hear someone say.

“I’m having the time of my life today. I’m having a really great day,” swears another.

Boys have Greek letters painted on their torsos. Girls walk in groups from house to house asking each other, “Who are you supporting?” They run down Webster Avenue carrying half-empty bottles of wine. I watch a boy in a wheelchair, knees bandaged, be wheeled from frat basement to frat basement through masses of sweaty, screaming onlookers.

In Beta, another boy, wearing headphones and dark sunglasses, tells me he has a concussion. He hit his head on the ceiling, playing pong. “I’m not missing this!” he says.

The bracket, complete with the schedule and location of the games, has circulated throughout the Greek houses via Google spreadsheet. There are five rounds. Each team consumes six beers each round if they lose, less (usually) if they win. The finalists will have consumed around 15 beers apiece in the span of four and a half hours, not including pre-tournament warmups. Puking is generally necessary to keep playing, but rules forbid excessive purging—typically, one “boot” per game. Supporters of each team tote loaves of bread, jugs of water, bottles of Gatorade—anything to soak up the beer and keep their players sharp.

Dartmouth pong—half ping-pong, half drinking game—isn’t your average beer pong.

It is played in unspoken rituals: Partners fist-bump after they make a “hit.” They dap each other up after they “sink” the ball. If the ball hits the table’s edge, everyone slams their paddles on the edge. At the end of the game, all players hug—even opponents. I find this strangely endearing.

Pong bridges work and play. It’s played drunkenly in dank basements that reek of bodies and beer. It’s also played with water, at 10 a.m., between classes. It inspires YouTube videos on serving techniques and facilitates hookups. Over and over, I hear the same thing—Pong brings us together; it’s universal.

“It’s pong, it’s embedded in Dartmouth culture,” a Gamma Delta Chi brother says.

“I think pong is definitely a good community-building exercise,” another brother affirms. “It’s inclusive.”

“It brings the brotherhood together.”

“It’s something that’s a really integral part of the Dartmouth experience, you know, for better or for worse.”

Tensions are high in GDX. A Phi Delt chorus rises: “Zete sucks a**! Zete drinks water! Zete can’t drink!”

I recognize one of the Phi Delt chanters as a friend from freshman year. I watch him cup his hands to his mouth, bend over, and yell “Zete sucks a**!” into the ears of one of the Zete players.

A moment later, the crowd yells and points, contesting a hit. My friend, towering over the two Zetes, spits out, “F*** you! F*** you! Learn how to mother******* PLAY!” His buddies pull him back.

The boys talk trash. The girls, on the other hand, wield banners. Some carry supportive messages—“Evan & Colton have my heart” and “When I die bury me in Beta Alpha Omega.” Others are less friendly: “Sorry you couldn’t get into a normal frat” and “SAE Cheats (on women)” and “Daddy’s money can’t win you Masters.”

“Some posters can be pretty offensive, and some people yell stuff to the refs that they shouldn’t,” one boy tells me later. “But that’s, like, every single sporting event ever. I feel like this is fun.”

“A society needs something to rally around,” another boy says. “For some schools, it’s football, and some schools are basketball schools. Dartmouth is a pong school, and this is our sport.”

It’s down to the wire, and the crowd is tense.

Finally, the Phi Delt team hits the ball on the edge of the cup. They’ve won the round. People yell and embrace. As is tradition, one of the Phi Delts grabs the edge of the pong table and shoves it upward. Phi Delts slam the board like a drum. It slides off the two trash cans supporting it and toward me. I watch in horror as the board lands on my exposed toes. As I begin to register the pain, a friend grabs my arm and yanks me away.

Later, I see a boy walk carefully out of Beta, looking down at his feet and telling his friend, “It’s only the right one that really hurts.” On one foot, his big toe is completely busted—the nail half off and bloodied. On the other, the top of his foot is a deep purple, bleeding lightly.

He tells me the table came down on his foot after it was flipped after a different match. “Not a fun time, but it happens.” He sounds resigned.

“Did you see that Alpha Chi?” a friend asks me later. “The one with the two bloody lines on his chest? A pong table fell into him, too.”

“For some schools, it’s football. Dartmouth is a pong school.”

“I don’t even need to boot right now,” a boy tells his buddy as they cross the GDX lawn. He’s playing for Sigma Alpha Epsilon and on his way to the quarterfinals game. He’s pink, sweaty, and ecstatic. “Oh my God,” he tells me as we reach the porch. “This is the greatest sporting event in the history of sporting events. There has never been something that has made me feel as good as today has been.”

Two GDX refs, wearing only boxers, watch one of the AXAs lay his arms across the table’s edge, ensuring his cups are squarely in the middle.

All eyes are trained on the board. Play begins.

SAE sinks a cup and their two players turn, unsmiling, and salute each other. My friend, wearing an AXA hat, writes “Sink City” on a white board.

I notice an old SAE friend nearby. What does he think of all this, I ask.

“It brings us together. It’s one of the few events that I think as a whole grade we really do appreciate,” he says. “It does tend to bring some of the worst out of it, but also some of the best.”

I ask him for an example of the worst and the best.

“Lots of heckling, and heckling leads to, you know, physical confrontations.” This Masters, he assures me, has been calm. “We’ve been pretty peaceful about mediating things.”

We’re standing at the corner of the basement, by the stairs. A man in the stairwell catches my eye. He looks to be somewhere between 40 and 50 years old. His hair is graying at the edge of his baseball cap, which is on backward. He wears thin rectangular-frame glasses, a gray button-up, and a gold chain around his neck. I watch him sip on a bottle of pink Vitaminwater. He’s hanging behind the crowd, just far enough up the stairwell where he won’t be easily seen.

“Who is that?” I ask a boy near me.

“A trustee of SAE,” he says. When SAE makes a hit and the crowd erupts in cheers, I watch the man pump his fist triumphantly.

“Oh, he’s so creepy, he’s around all the time,” a friend tells me later when I describe the man. “I think he lives around here. His daughter might be wanting to go here.”

When the game ends in an AXA win, I turn back to the stairwell to see the man already disappearing up the stairs. I scramble to follow and catch up on the GDX porch. “Excuse me!” I say, breathless. “Could I talk to you?”

He smiles ever so slightly. “About what?”

“About Masters,” I say. His stare makes me nervous. I ask if I can record him, intending to include him in this story.

“I don’t want to be recorded,” he says.

I think for a moment, then decide to let him go. “Actually, never mind,” I say.

He smiles. “Thank you.” He turns and walks to the street.

I keep picturing him in the corner, surrounded by screaming, drunk 20-year-olds playing pong, sipping his pink water and watching. Like he is still one of us.

“It’s one of the few events that I think as a whole grade we really do appreciate.”

When I approach the four boys on the Beta porch, they’re suspicious.

“Could I ask you some questions?” I say.

“Are you with The D?” one of them asks.

“No.”

“We can’t talk to anyone from The D.” He’s definitive.

“I’m not from The D!” I assure him.

They share glances.

Two days earlier, all students received an email from Dean Scott Brown expressing concern over a “masters pong tournament” the administration knew was coming up that weekend: “We care deeply about you, and we are concerned because the tournament carries serious risk for potential hazing (based on the possibility of physical/psychological injury) and the potential for coercion (arising from the structured tournament setting).” Brown threatened disciplinary sanctions for organizations and individuals who violated guidelines intended to prevent these harms.

I understand the Betas’ hesitancy. They think I’m a student journalist poised to rat them out. I explain that I’m motivated only by my own curiosity, by the spectacle of the tournament.

“I think a lot of it is, it brings Greek houses together,” says one.

“I think it’s the same as supporting sports teams in a community,” another says.

“There are some problematic aspects,” replies another.

“Like what?” I ask.

Before he can respond, the one boy who had been silent pipes in. “No problematic aspects!”

They glance at each other, then back at me. “Yeah, no problematic aspects,” he says.

Over at SAE, the basement is a swamp, the air thick and humid. I touch the walls. They’re slippery.

A rowdy crowd of spectators line the room, fanning themselves with their hands.

We find a spot on a ledge by a small window fitted with a broken air conditioning unit. The only fresh air coming in is through a gap that barely fits my forearm. Within minutes, sweat pours down my face, my neck, my legs.

“It was warmer yesterday,” one girl assures me. “There was so much sweat pouring down my leg it looked like I peed myself.”

The game starts.

“My skin is peeling off of me,” someone whines. “American Boy” by Estelle is playing so loud that I can feel it in my chest. My friend stares vacantly at the game. I look out at the sea of people, jeering and yelling.

“One day, so many of these people will have six-figure salaries,” she says. “Some in, like, under four years.”

“I’ll f*** Beta up, b****!” someone yells.

One of the Beta players takes a hit from a Juul and blows a vaporous cloud into the air.

The AXA dips the ball into a cup of beer, then serves. Across the room, a girl holds a sign: “Beta body shames women.”

Near the end of the game, Alpha Chi has just a half-cup left, Beta a whole. The music has stopped. It’s tense. The room is a chorus of shhhhhhhhhhhhhs.

After every hit of the paddle, a group whispers “Oh s***! Oh s***!”

Finally, amid near silence, AXA sinks their last cup to win. The noise is huge. Someone flips the table. The AXAs are hugging, chanting “Alpha Chi! Alpha Chi!”

“Let’s leave,” I tell a friend. On the other side of the room, someone has knocked an AC unit out of a window. I watch people shimmy through the narrow gap and out into the fresh air. We follow.

I swing my leg over the ledge and crawl out into the grass. The air is like a cold shower.

Kira Parrish-Penny is the Edward Connery Lathem ’51 Special Collections Fellow at Rauner Library.