Institutions normally evolve by accretion, avoiding uncertain change. But occasionally they invite the unknown, as Dartmouth did in the late 1960s when President John Sloan Dickey ’29 approved a radical experiment. It was called Foundation Years, a program that identified some Chicago gang leaders as promising students and enrolled them in the College.

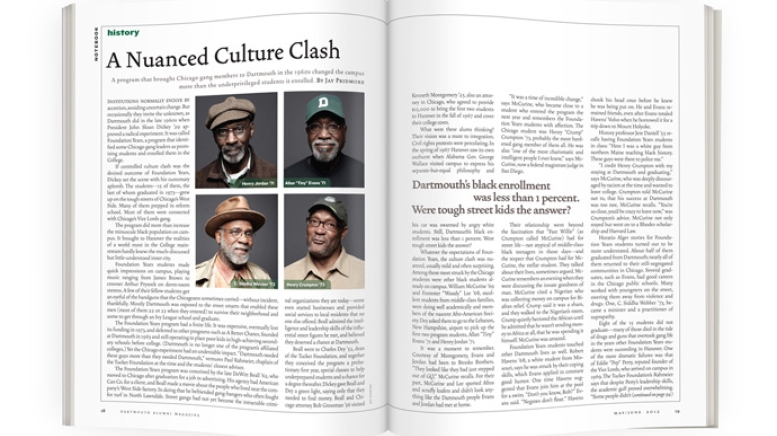

If controlled culture clash was the desired outcome of Foundation Years, Dickey set the scene with his customary aplomb. The students—15 of them, the last of whom graduated in 1973—grew up on the tough streets of Chicago’s West Side. Many of them prepped in reform school. Most of them were connected with Chicago’s Vice Lords gang.

The program did more than increase the minuscule black population on campus. It brought to Hanover the realities of a world most in the College mainstream hardly knew: the much-discussed but little-understood inner city.

Foundation Years students made quick impressions on campus, playing music ranging from James Brown to crooner Arthur Prysock on dorm-room stereos. A few of their fellow students got an eyeful of the handguns that the Chicagoans sometimes carried—without incident, thankfully. Mostly Dartmouth was exposed to the street smarts that enabled these men (most of them 22 or 23 when they entered) to survive their neighborhood and some to get through an Ivy League school and graduate.

The Foundation Years program had a finite life. It was expensive, eventually lost its funding in 1973, and deferred to other programs such as A Better Chance, founded at Dartmouth in 1963 and still operating to place poor kids in high-achieving secondary schools before college. (Dartmouth is no longer one of the program’s affiliated colleges.) Yet the Chicago experiment had an undeniable impact. “Dartmouth needed these guys more than they needed Dartmouth,” ventures Paul Rahmeier, chaplain of the Tucker Foundation at the time and the students’ closest advisor.

The Foundation Years program was conceived by the late DeWitt Beall ’62, who moved to Chicago after graduation for a job in advertising. His agency had American Can Co. for a client, and Beall made a movie about the people who lived near the company’s West Side factory. In doing that he befriended gang-bangers who often fought for turf in North Lawndale. Street gangs had not yet become the intractable criminal organizations they are today—some even started businesses and provided social services to local residents that no one else offered. Beall admired the intelligence and leadership skills of the influential street figures he met, and believed they deserved a chance at Dartmouth.

Beall went to Charles Dey ’52, dean of the Tucker Foundation, and together they conceived the program: a probationary first year, special classes to help underprepared students and a chance for a degree thereafter. Dickey gave Beall and Dey a green light, saying only that they needed to find money. Beall and Chicago attorney Bob Grossman ’56 visited Kenneth Montgomery ’25, also an attorney in Chicago, who agreed to provide $15,000 to bring the first two students to Hanover in the fall of 1967 and cover their college costs.

What were these alums thinking? Their vision was a route to integration. Civil rights protests were percolating. In the spring of 1967 Hanover saw its own outburst when Alabama Gov. George Wallace visited campus to express his separate-but-equal philosophy and his car was swarmed by angry white students. Still, Dartmouth’s black enrollment was less than 1 percent. Were tough street kids the answer?

Whatever the expectations of Foundation Years, the culture clash was nuanced, usually mild and often surprising. Among those most struck by the Chicago students were other black students already on campus. William McCurine ’69 and Forrester “Woody” Lee ’68, excellent students from middle-class families, were doing well academically and members of the nascent Afro-American Society. Dey asked them to go to the Lebanon, New Hampshire, airport to pick up the first two program students, Allan “Tiny” Evans ’71 and Henry Jordan ’71.

It was a moment to remember. Courtesy of Montgomery, Evans and Jordan had been to Brooks Brothers. “They looked like they had just stepped out of GQ,” McCurine recalls. For their part, McCurine and Lee sported Afros and scruffy loafers and didn’t look anything like the Dartmouth people Evans and Jordan had met at home.

“It was a time of incredible change,” says McCurine, who became close to a student who entered the program the next year and remembers the Foundation Years students with affection. The Chicago student was Henry “Crump” Crumpton ’73, probably the most hardened gang member of them all. He was also “one of the most charismatic and intelligent people I ever knew,” says McCurine, now a federal magistrate judge in San Diego.

Their relationship went beyond the fascination that “Fast Willie” (as Crumpton called McCurine) had for street life—not atypical of middle-class black teenagers in those days—and the respect that Crumpton had for McCurine, the stellar student. They talked about their lives, sometimes argued. McCurine remembers an evening when they were discussing the innate goodness of man. McCurine cited a Nigerian who was collecting money on campus for Biafran relief. Crump said it was a sham, and they walked to the Nigerian’s room. Crump quietly hectored the African until he admitted that he wasn’t sending money to Africa at all, that he was spending it himself. McCurine was amazed.

Foundation Years students touched other Dartmouth lives as well. Robert Havens ’68, a white student from Missouri, says he was struck by their coping skills, which Evans applied in constant good humor. One time Havens suggested that Evans join him at the pool for a swim. “Don’t you know, Bob?” Evans said. “Negroes don’t float.” Havens shook his head once before he knew he was being put on. He and Evans remained friends, even after Evans totaled Havens’ Volvo when he borrowed it for a trip down to Mount Holyoke.

History professor Jere Daniell ’55 recalls having Foundation Years students in class: “Here I was a white guy from northern Maine teaching black history. These guys were there to police me.”

“I credit Henry Crumpton with my staying at Dartmouth and graduating,” says McCurine, who was deeply discouraged by racism at the time and wanted to leave college. Crumpton told McCurine not to, that his success at Dartmouth was too rare, McCurine recalls. “You’re so close, you’d be crazy to leave now,” was Crumpton’s advice. McCurine not only stayed but went on to a Rhodes scholarship and Harvard Law.

Horatio Alger stories for Foundation Years students turned out to be more understated. About half of them graduated from Dartmouth; nearly all of them returned to their still-segregated communities in Chicago. Several graduates, such as Evans, had good careers in the Chicago public schools. Many worked with youngsters on the street, steering them away from violence and drugs. One, C. Siddha Webber ’73, became a minister and a practitioner of naprapathy.

Eight of the 15 students did not graduate—many of those died in the tide of drugs and guns that overtook gang life in the years other Foundation Years students were succeeding in Hanover. One of the more dramatic failures was that of Eddie “Pep” Perry, reputed founder of the Vice Lords, who arrived on campus in 1969. The Tucker Foundation’s Rahmeier says that despite Perry’s leadership skills, the academic gulf proved overwhelming. “Some people didn’t want to ask for the help that they needed,” says Rahmeier. “They were too proud. That was Pep”—who went back to the street, used hard drugs and died a few years later.

Foundation Years had mixed results but lasting value. For the deepest lessons, one thinks of Crumpton. He left Dartmouth about a year from graduation. “I couldn’t give a real reason why I left,” he says. A friend says Crumpton just got bored in Hanover. Back in Chicago, Crumpton was a street hustler. He lost at least two decades to addictions, and fell out of touch with friends such as McCurine and Lee. He remains haunted by his Dartmouth years. “It was like I wasn’t allowed to fail,” he says.

He’s clean now, and at least one belated lesson of Foundation Years, and even of the nature of change, lies in his recovery. He’s an Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) sponsor who takes calls day and night. AA forces him to think about other people’s dramas, which he did not do when he was the toughest gang member in Hanover.

When he was a student no one doubted Crumpton’s courage and character, which were what got him into Dartmouth. But the key to his success turned out to be the sheer curiosity that accompanies change at any level. Curiosity drove McCurine’s friendship with Crumpton. (They were happily reunited last year.) It was behind the relationship between Havens, who had a career in public health, and Evans. That same intense curiosity connected Rahmeier, whose career was dedicated to education of first-generation college students, to the Foundation Years students, whom he remembers to a man.

Lee, now a professor of cardiology and assistant dean of multicultural affairs at Yale School of Medicine, puts it another way: “For me the Foundation Years told us that anything and everything was possible. It opened doors. It kicked them wide open.”

Jay Pridmore writes about architecture and urban affairs. He lives in Chicago.