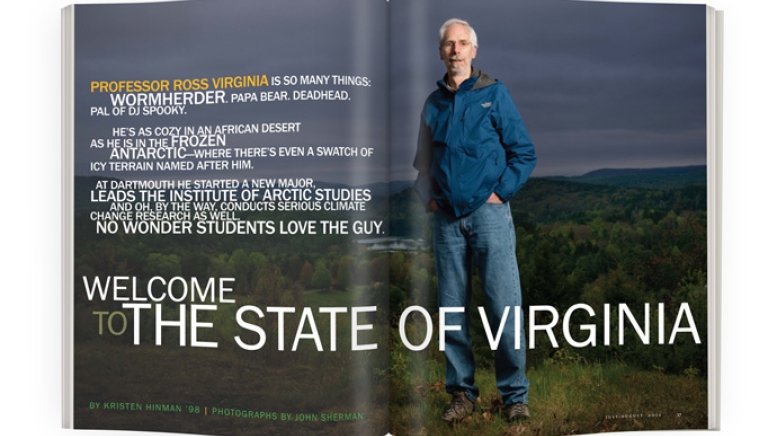

Only at the end of Ross Virginia’s class, “Pole to Pole: Environmental Issues of the Earth’s Cold Regions,” do students get to eyeball his so-called “hero shot.”

By this time they’ve mastered the difference between global warming and climate change and immersed themselves in College-owned artifacts from polar explorations. They’ve seen pictures of Virginia’s own classroom, if you will: the vast, frozen deserts of the “pork chop-shaped” Antarctica, where Virginia has studied soil and critters for two decades as part of a research team dubbed The Wormherders. They’ve heard him compare the continent to Mars. Heck, they’ve even handled samples of its soft gray dirt. Finally, the photo appears: His cloud-white beard shining in the December sun, bright-red parka and white moon boots popping against a backdrop of blue, Virginia smiles big from his footing in Virginia Valley.

As in the upland terrain at the 77th southern parallel that the U.S. Board on Geographic Names put on the books in Virginia’s honor in 2004.

The point isn’t to “self-call,” as Dartmouth students would put it. It’s to say: “If you can’t find a hero shot a couple years out of Dartmouth, or you can’t envision what your hero shot will be, then maybe it’s time to think, ‘What am I doing?’ To take a measure of your life,” explains Virginia, “there should be a hero shot in your life somewhere. You should be passionate about whatever it is you’re doing or hoping to do.”

Surprisingly, you won’t find the image in the memento mash-up that adorns Virginia’s office in Steele. Amid this hardcore Deadhead’s collection of music memorabilia, the photos on display show Virginia with students. Listen as he ticks off their biographical sketches—including details of the alums’ current doings—and the picture of a pioneering scientist gradually takes on a richer dimension.

“I think you can see that for him, the passion is about each of his students finding their own path,” says Courtney Hammond ’11, who reports that her Dartmouth experience completely changed after she met Virginia. “It might not be the same as his, but if he can help you on whatever path you’re passionate about, he’ll do so. He’s a total papa bear.”

It’s hard to believe Virginia’s claim that he was clueless about liberal arts in 1992 when he left a job teaching biology at San Diego State University for Dartmouth. As a former colleague recalls, Virginia wasn’t the front-runner to helm the environmental studies program founded in 1970 by James Hornig. Yet Virginia’s energy and ability to connect one-on-one with selection committee members impressed them.

For Virginia the Hanover gig was a dream come true, literally. He was the first kid his high school ever invited to a Dartmouth recruiting night, he says. He can still recall shopping with his mother for a sport coat and the heft of the student handbook placed into his hands at the event. He became obsessed with taking engineering classes at Thayer. Because of a sudden change in his family’s financial situation, Virginia never got to Hanover—until his job interview. During the first break that day, he recalls, “I took a chance and I ran down to Thayer, just to look at it and think: It took awhile, but I got here!”

Prior to his hiring, Dartmouth undergraduates could earn only a certificate in environmental studies. Within four years of his arrival as a tenured professor and program chair, Virginia secured faculty support for an environmental studies major.

Now, 15 years later, the program graduates up to 40 students a year and boasts eight tenured or tenure-track faculty, plus a dozen accomplished adjuncts. Its foreign study program (FSP) in southern Africa is considered a standout. In 1999 Virginia also helped legitimize a fledgling student-led operation, the Dartmouth Organic Farm, by creating a sophomore-summer class on sustainable agriculture replete with lab periods at the Route 10 property. “When I was chair, that course caused more problems than any other in the program,” remembers professor Andrew Friedland. “Why, you may ask? Because of the over-demand.” (Virginia has since handed off the class; one of his first students, who subsequently acquired a Ph.D. in sustainable agriculture, taught it last summer.)

Along the way Virginia has attracted an array of thought leaders to campus, from Michael Pollan, author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma and an expert on food politics, to DJ Spooky, an experimental musician and artist who has composed works involving the sights and sounds of Antarctica. Bureaucratically speaking, environmental studies is still considered a Dartmouth “program,” as opposed to a full-fledged “department,” but one could argue that the scope of its offerings epitomizes the liberal arts. Scientists, economists, social and political scientists, and humanists call the environmental studies program home.

In 2003 Virginia became director of the Institute of Arctic Studies at the John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding, founded 15 years ago. According to former Dickey Center Director Kenneth Yalowitz, Virginia “put it on the map, nationally and internationally.” In 2007 Virginia lured a major global research meeting to campus. Policymakers soon began trekking to Hanover. Virginia initiated an exchange program for Greenlandic students and stoked the interest of undergraduates seeking related research fellowships. “I often say to Virginia, ‘I wish I could clone you,’ ” says Yalowitz. “He understands the academic atmosphere beautifully, but he also has a very strong affinity for policy and knows how to communicate with policymakers.

He’s that rare scientist who can bridge both of those worlds.”

The center not only took Virginia to the opposite end of the earth, it expanded his horizons in ways he never expected. He discovered he wasn’t content with the academic paradigm: conducting fieldwork, hibernating in the lab and publishing. Climate-change scientists have much to do to explain the terrain of current research and trends to policymakers, Virginia posited. He kept asking himself, “How else could I contribute?” Virginia found the answer in his latest project: training the next generation of graduate students with help from a five-year, $3-million Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship (IGERT) grant from the National Science Foundation. The IGERT is intended to get Ph.D.-candidate scientists and engineers collaborating across disciplines to advance science for the greater good. Virginia designed Dartmouth’s program around polar environmental change and incorporated a fieldwork and policy component in Greenland, at the front lines of climate change.

At 61, he is starting to think more about his legacy. Colleagues, however, say Virginia shows no signs of decelerating. “If you look at the pattern of Ross’ life since he’s been at Dartmouth, it’s been a pattern of quiet innovation,” observes Jack Shepherd, professor emeritus of environmental studies. “He changed the program, he improved its FSP and now he’s gotten this big grant, expanding the College’s international reach yet again. I suspect as long as he can continue working on [the IGERT] and generating ideas for it, which I think he’s been brilliant at, he’ll keep going. Why not?”

Shortly after returning from Greenland last summer Virginia was holing up in one of his favorite places, Rauner Special Collections Library. A theater production depicting Sir Ernest Shackleton’s trans-Antarctic voyage of 1914-17 was about to debut at the Hop, and Virginia was busy assembling a complementary exhibit featuring excerpts from the only known diary to survive the shipwrecked adventure. “I’ve been having a little too much fun with it,” he says one afternoon while walking to Rauner.

The journal is housed in Dartmouth’s Stefansson Collection on Polar Exploration, a trove of primary materials bequeathed to the College. Getting students to use it is an integral part of Virginia’s undergraduate “Pole to Pole” class. Still, it’s rare for Virginia—who swoops into Antarctica on military jets—to have time to linger over the texts, re-imagining his predecessors racing to the poles via ship and sled. Paging through the journal “raises the hair on the back of my neck,” he says with a shudder.

If the amenities have changed—Virginia can read his e-mail in Antarctica—the spirit of the endeavors has hardly shifted. “They’re facing serious hardship, thinking constantly about their next meal and where it’s going to come from, and then on the next page you’ll see a beautiful description of an aurora or of how nice somebody is,” Virginia says of his forebears’ archive. “People like me, we’re working in small groups and it’s pretty intense, but there’s a collective experience and a sense of community that comes out of that. You see it so much more intensely in a diary like this.”

Virginia grew up reading about the race to the pole as a kid in Syracuse, the snow belt of central New York. But it’s not as if he saw himself retracing Shackleton’s steps. After Dartmouth didn’t pan out he lived at home and worked odd jobs to fund studies of forest biology at SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Eager for independence, he went west for graduate studies in ecology at the University of California-Davis, acclimating easily to the beats of the San Francisco counterculture and the seductive peaks of the Sierra Nevada. (“I didn’t do all those psychedelic drugs,” he insists.) Working on the subject of nitrogen fixation in the lab of a premier soil scientist left the biggest mark on Virginia, propelling his lifelong fascination with the ground beneath his feet and the myriad ways its inner workings affect the environment.

In the late 1980s, almost a decade after finishing his Ph.D., he was consumed with a project involving mesquite in the New Mexico desert when a line of questioning stumped him and a fellow researcher. They wanted to know what determined the biodiversity of life in soils and whether plants played a role. They needed an unusual testing ground: a place with little to no plant life. A colleague half-jokingly suggested Antarctica. “We wrote up this grant, kind of on a lark, figuring we’d go down once, do a quick study and that’d be it,” Virginia recalls.

Twenty years later he’s still telling students about the first time a helicopter plunked his three-person research team into Antarctica’s dry valleys. “I remember us watching that helicopter just fly, fly away. And then just how incredibly quiet it was. We were standing there, just frozen, just overwhelmed by the experience, the scale of the place, thinking: What could we possibly do in this gigantic environment? We literally couldn’t do anything for a while. Finally, it was like, okay, wait a minute, we wrote a grant, we thought this through, we have questions we want to answer, we’re trained professional scientists: We can do this. We started sampling. The next thing we know, there’s this helicopter coming down right on top of us. We didn’t even hear it. We were just so absorbed with what we were doing. You dive in and you get hooked.”

Exotic, sure, but the conditions are extreme. The researchers spend a field season, usually four to six weeks, living in prefab housing and tents. Helos intermittently deposit them in remote areas for undetermined spells; the hope is that weather and visibility will cooperate for the return trip. Just in case, they take survival bags with provisions and supplies to last three days on the cold, dry, windy terrain. Virginia’s packing list for Antarctica is short: iPod, a bottle of whiskey and his “rockin’ Altoids box,” a tiny set of do-it-yourself speakers that Matthew Poage, Adv’91, made for him. The stuff accompanies Virginia to an ice-free area that is unlike 98 percent of the continent’s terrain and comprises some of the oldest exposed surfaces on the planet. The soil in these valleys is frozen most of the year, yet as the earth warms due to increased burning of fossil fuels, trapped carbon is released from the permafrost. Virginia looks at the effect of climate change on life in the soil and its role in the global carbon cycle.

Given the stressful conditions, it’s refreshing to see how laid-back and jovial Virginia can be in the field, observers say. Gifford Wong, a Ph.D. candidate in Dartmouth’s IGERT program who used to pilot helicopters in Antarctica, relates how Virginia’s team always came equipped with a themed T-shirt and plenty of practical jokes. “They were always a lot of fun to work with,” says Wong. “They had a great esprit de corps.”

Shepherd, the professor emeritus, says the same spirit underscored Virginia’s guest lectures on the environmental studies FSP in southern Africa. “The students loved him because he treated them the way he treats his own kids, which was fairly and openly and with great humor—and a cold beer, if you could get ahold of one out in the desert. He’d come in for two weeks, and it was like a movie star had arrived. The kids would cheer him on and sit around the campfire with him and he’d give these wonderful, brilliant lectures on the differences between cold and hot desert ecologies. The kids would convert—they would leave Africa wanting to go to Antarctica with him.”

One thing Emma Virginia ’09 always avoided at Dartmouth was a party at Sigma Alpha Epsilon. “It was right outside my dad’s office window, and I didn’t want to see his lights on at 2 a.m.,” she tells me. Ross Virginia has a reputation for working late and on Sundays. He hates to fly and rarely takes a vacation. Emma says her mother, a botanist by training who holds down the family’s pastoral fort in Norwich, Vermont, is used to Virginia’s workaholic ways. In fact, she’s stipulated that lest he succumb to his relaxation-mode fixation with Law & Order, he must acquire two hobbies in order to retire. The Grateful Dead. Doesn’t. Count.

Virginia became a Deadhead at Davis, but the affinity has heightened in the last two decades. The band plays on a constant loop in his office, where a screensaver features Dead-related images. After the Dead dissolved Virginia began following its cover bands, Furthur and Dark Star Orchestra, attending hundreds of shows around the country with fellow scientist Michael Poage ’90, Adv’00. On campus—where Virginia is known for wearing tie-dyed T-shirts and launching 99 percent of his “Pole to Pole” lectures with a clip of the Dead—students would approach Emma in frats yelling, “Dude, I love your dad!”

Emma says her father’s obsession annoyed her endlessly until she joined him at a concert a few years ago and began to understand its appeal. “The old guys come up to him and go, ‘Oh, man, did I see you at the Albany show?’ And then the younger, just-starting-out Deadheads circle up to ask questions about shows from the ’70s and his favorites and all of this. It was really interesting to watch,” she says.

It was a couple years ago when Ross Virginia had the revelation that luring students into lectures via music was in sync with the school’s mission: “I realized, wait a minute—this is liberal arts! Why should I leave my music behind when I go into the classroom? Aren’t we supposed to be teaching students not to take all their different interests and separate them into boxes?” Virginia and Lee Witters, a professor of biochemistry, are conspiring to award former Dead drummer Mickey Hart an honorary degree for his international ethnomusicology work. And yes, the Dead has found its way to the Arctic. Since 2010 Virginia has marked the August 1 birthday of band founder Jerry Garcia by leading the IGERT cohort to a rock in Greenland where his colleague Meredith Kelly, assistant professor of earth sciences, is calculating the length of time that sediment has been exposed by the retreating ice sheet. There’s wine and a toast to the good that Garcia would see in scientists of different backgrounds coming together.

“Ross points out that the Grateful Dead were the original open-source rock ’n’ roll band,” explains biology professor Matt Ayres. “They went on tour and sold tickets to support themselves, but they encouraged people to record their music at their concerts and to share it. We talk a lot about this in science now, about the fact that one way we have to increase the rate of scientific productivity is by more efficient sharing of data and the code we use to analyze the data.…So what Ross is saying is that the Dead led the way.”

Virginia became fixated on obtaining the prestigious and competitive IGERT grant for Dartmouth in the mid-2000s. Since 1998 about 110 universities have received an award. Applicants have to emphasize collaborative research across disciplines. But the schools customize the focus and scope of their programs. Virginia submitted his first proposal in 2006. Dartmouth got turned down, but Virginia went back to his iMac and reapplied—twice. “We have [the IGERT] because Ross not only conceived of it but busted his ass over three years pretty much working by himself to get it funded,” says Ayres.

The grant-winning program on polar environmental change connects faculty members from Thayer and the College with Ph.D. candidates. Virginia devised a summer study in Greenland with a mix of field research and mind-melding with Greenlandic students, bureaucrats and politicians. He says the human component is important, considering that hundreds of researchers circulate in and out of Greenland every year yet never interact with the native population. “I don’t think every Dartmouth graduate student needs to be doing science to inform policy,” he says, “but I think every Dartmouth student should have an opportunity to understand what those linkages are and why it might be relevant to think about scientific questions policymakers ask.”

The third of five IGERT classes matriculated at Dartmouth last fall. One student is studying how air bubbles get trapped in ice—a record of how much carbon dioxide was in the atmosphere in the past. Another is looking at how climate change affects aquatic communities. As the climate warms, mosquito populations can expand, for example: What effect does that have on life? Virginia guesses that a fair number of the Ph.D.s will forgo careers in academia to work in applied settings. He’ll be there to high-five them come graduation—colleagues say he never misses a ceremony—and yes, in the years to come, he’ll be watching his e-mail for their hero shots.

“I could write a few more papers. Or, working with my colleagues through IGERT, I can have some bearing on the productivity and the output of all these students,” he says of the future. “That’s what I love about Dartmouth. Every one of my students is doing something very cool, and I can see a little piece that I was engaged with.”

Kristen Hinman edits politics and policy coverage for Bloomberg Businessweek magazine.