FROM THE ARCHIVES

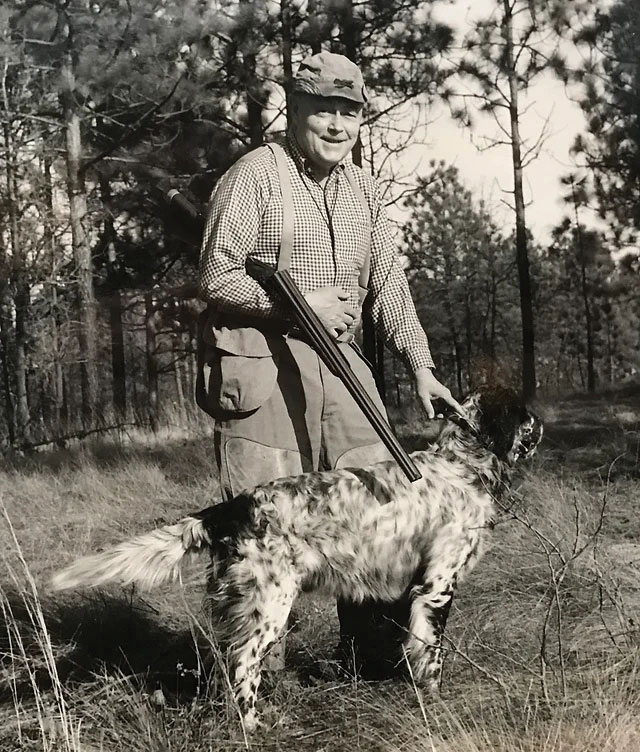

My dog made up my mind to live in Hanover. My dog is a large English setter, who acquired me when he was about six months old, and who has been making up my mind for him ever since. When we go out on a leash together, he decides whether to run or walk or halt abruptly at the corner lamppost to mail a letter. He decides what time I get up in the morning, and which chair I can sit in (except the overstuffed chair in the living room, which is his). Naturally, when the time came to choose a place in which to live, I left the whole decision to my dog.

He picked Hanover because he says it is a very good town for dogs. A lot of dogs seem to feel the same way, because the town is full of them. I don’t know how the word gets around. Maybe the resident dogs leave secret signs on trees for other dogs to read, the way tramps do: “This is a good jungle, no cops to chase you, and plenty of food to eat.”

Hanover is the kind of town where dogs wander un-escorted up and down the street, and the butchers save bones to give them, and when you eat at the Hanover Inn, which is one of the best eating places in all New England, the waitress wraps up your table scraps in a paper napkin so you can take them out to your dog in the car.

A good dog town is a friendly town, small enough to call up when a neighbor’s dog strays from home, and easy-going enough to stop the car if a dog is crossing the street. Hanover is like that.

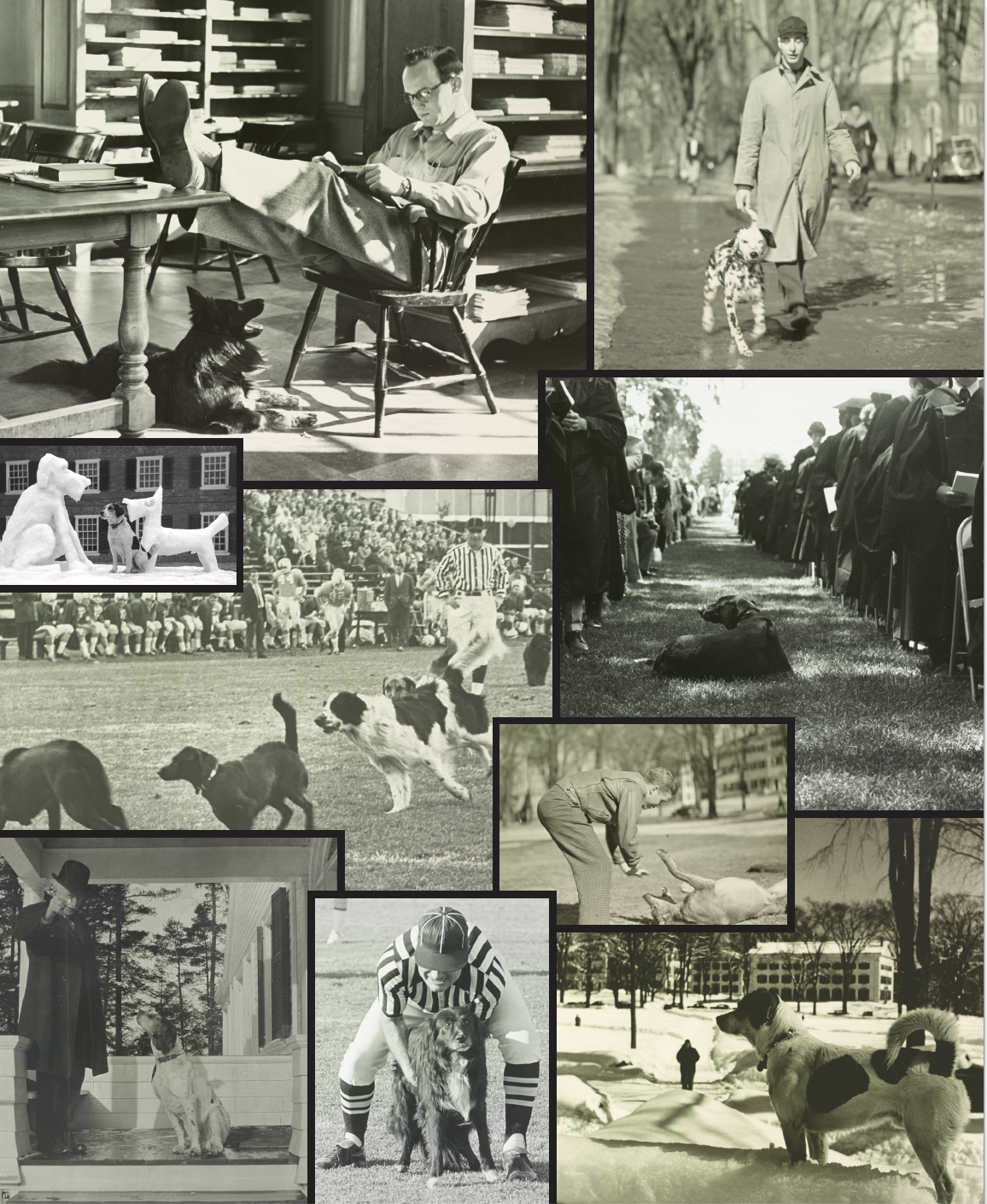

Maybe it’s because it is a college town: Dogs prefer students, because they’re the same age. You’ll always see a dozen or so dogs on the Dartmouth campus, dashing between the legs of undergraduates playing softball, or lolling on the grass beside a group of collegians with shirts peeled off, sunbathing on a warm spring afternoon. Stray dogs are always running out on the football field and getting in the players’ way, and once an English setter named Bucky, who owns the Secretary of the College, fell in love with the captain of the baseball team and held up the Dartmouth-Harvard game for 10 minutes because he insisted on lying on the pitcher’s mound at his hero’s feet.

A lot of Dartmouth people are owned by dogs. President John Sloan Dickey belongs to a big golden retriever who sits beside the president’s desk in the administration building all day and walks him home every night on a leash, to make sure that Dr. Dickey doesn’t run away. During a fraternity initiation one of the pledges had to survey all the Hanover dogs, to determine which was the largest. He measured 57 dogs, and Dr. Dickey’s was second. (The winner was an elderly St. Bernard who is associated with the English Department.)

Hanover is a small town, and it is unspoiled by progress. No railroad scatters its soot over the neat white frame houses, no great cement highway bisects it. It’s still a small town. When you pick up the phone, you ask the operator for a name instead of a number. The stores along its Main Street are as up-to-date as those of any big city, but shopkeepers call you by your first name. It has a fine modern hospital and efficient schools and post office and movie theater, but on the edge of town the fields are being plowed for corn, and the pine-covered hills are loud with grouse in the fall, and every December men in boots and checkered shirts, with hunting licenses pinned to their caps, lounge in the doorway of Campion’s store and discuss the 10-point buck that Joe seen last night up to Moose Mowntin.

A college town is not like other towns. Its life changes with the college year. All summer long, when Dartmouth is in recess, Hanover lazes about its local business, and the stores are half-empty, and there is room to park on Main Street. But the place seems empty, a little older and even a little lonely. The townspeople say to each other: “It’s certainly nice to have a little peace and quiet for a change!” But the words echo hollowly.

Then in the early fall, when the air quickens with the first cool nights and the katydids predict frost in six more weeks, the town suddenly stirs to life. Warm new blood gushes through its veins, and it is 20 years old again. Two thousand hand-picked young men, the best of America’s new generation, pour into town by train and plane and private car to start another school year. They stroll down Main Street in dungarees and T-shirts and battered white bucks, they jam into the flick—it’s the New Nugget now—and howl insults at the lovers on the screen, they crowd along the lunch counters, their heels locked around the rungs of the stools, gulping milkshakes and poring over The Daily D.

Sometimes the town burghers shudder, when the boom of a football rally shakes the night air, or when a swarm of out-of-towners and uninvited guests invades Dartmouth’s traditional Winter Carnival and turns the village streets into bedlam. Sometimes there are brushes with the local gendarmes, when youth erupts violently after a siege of exams.

Once, a few years ago, the town fathers made the tactical mistake of passing a law requiring the students at Dartmouth to pay a poll tax in order to vote. The students paid the tax. Then, in March, they moved in on the annual town-meeting, outnumbering the local residents two to one, and within an hour they had voted for such long-needed improvements as a beer-bubbler in the center of the campus and a new Town Hall 500 feet high and six feet square. The poll tax was revoked.

I like Hanover in the winter, when ski boots squeak on the hard-packed snow and ski racks are fastened to the tops of cars headed for Balch Hill.

I like it in the spring, when the duckboards are down for students to cross the muddy green, and northbound geese honk overhead, and the opening day of trout season is only a couple of weeks away.

Best of all I like it in October, when the tang of wood-smoke is in the air and the gold and crimson hills that surround the town are like folded Persian carpets, and on a fine fall afternoon, when classes are over, Dartmouth students and townspeople alike shoulder their shotguns and take off for the grouse and woodcock covers, with a setter or a pointer or a spaniel tagging at their heels.

Which is why my bird dog would rather live here in Hanover than any other place in the world. I’m glad that he decided as he did. I feel the same way.

Corey Ford (1902-69) was an outdoorsman, writer, and rugby enthusiast. He lived in Hanover during the 1950s and 1960s with two English setters, Cider and Tober. Ford sponsored the Dartmouth Boxing Club, and the rugby fieldhouse is named for him. This essay, written in 1952, appeared in DAM in 1978.