After graduation I didn’t visit Dartmouth for more than two decades. Let’s say that we drifted apart. In 2017 my husband was running an ultrarace near Hanover. I decided to show the kids “where Mommy went to school.”

Driving over the bridge, I took in my lost landscape, parent-narrating all the places I had loved: Ledyard Canoe Club, Sanborn, and Baker Library, in its Orozco-painted magnificence. For some reason Webster Avenue’s pull also remained as strong as its long-ago basement odors. I curved the car around Occom Pond and then slow-rolled down Frat Row.

“Mom. Mom. What is that?”

My 10-year-old daughter was pointing to a young man covered in red paint, wearing only a jockstrap. He was tossing a football on a front lawn with friends who had opted for clothes. It was 1 p.m. on a Saturday.

“That’s a fraternity, honey,” I offered. “These students have likely been drinking for several hours now, so that might explain their choices.”

“Oh my gosh,” said my son. He was 7.

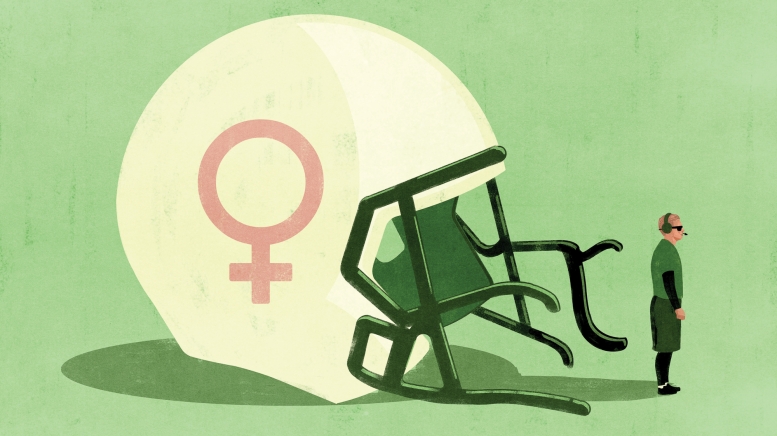

I laughed, and my kids saw through it. Dartmouth was still Dartmouth—still wearing that old patina of masculinity. It still tossed footballs mostly naked.

I had no idea that this strange soup of memory—the casual misogyny, the dynamics of athletics and fraternities—was about to take a mind-bending turn.

I discovered the ballast I needed to begin recalibrating my relationship with Dartmouth.

Many of my campus memories involve what I will call “sport at the margins.” At the bonfire I circled gamely and sweated deeply in a turtleneck. During the Homecoming game I had difficulty focusing on game action, but ultimately ascertained that important plays were happening right there in the stands. So many rushes and gains between potential partners! So many surges and sacks!

My most luminous Dartmouth memories connect with classrooms, not playing fields: Professor Raúl Bueno-Chavez drawing a star on the board, then pretending to pluck it off and carrying it to a student who had shone in Spanish. In contrast, my memories of living on campus pulse with the anxiety of being unmoored from my family and calculating when I would next find myself in a fraternity basement—an ongoing social survival game in spaces managed by men.

To be clear: Frats and football are not the same thing, and in many ways they may actually be the opposite. As a high school English teacher, I have worked with scores of athletes whose understanding of community, form, and strategy all translate readily into noteworthy poetry and essay writing. Perhaps these experiences with football players—my learnings about the honor and hard work that football can engender—helped me understand what happened next.

In September 2018 a video interview popped up in my Facebook feed: “Meet College Football’s First Female Football Coach.” I had to check it again. I was not mistaken: Dartmouth had hired the first full-time Division I female coach, Callie Brownson, whose story was the stuff of dreams. In high school she had been turned away from her Alexandria, Virginia, football team, despite playing on boys’ teams as a child. After several years in women’s pro football and two gold medals with the U.S. women’s national football team, Brownson returned to her high school to coach, then interned with the New York Jets. She caught the attention of Dartmouth coach Buddy Teevens ’79, who invited her for an internship. Within two weeks he offered Brownson a full-time job.

I had to tell my students. Unsurprisingly, these young Philadelphians found much to consider in Brownson’s underdog story. That year we had been studying the “weight of history”—the concept that everyone relates differently to history based on who they are in the world. As students watched Brownson’s video, they noted the changes in her face and voice as she described being told that she could not play football. That moment weighed on each of us. In their journals, football players wrote about their relationships with their fathers; a state-ranked swimmer added Brownson to her list of female coaching heroes. Reading their words, I felt the weight of history shifting permanently. I discovered the ballast I needed to begin recalibrating my relationship with Dartmouth.

Coach Brownson agreed to join us for a postseason visit. By that time my 11th-graders had finished The Great Gatsby and could write either an essay or an introduction to Brownson’s presentation. There was one caveat—the intro writers would stand and deliver their remarks in an assembly during her visit.

They wrote, they revised, they showed up to host Brownson’s first event on campus where she demonstrated the skill of someone whose whole life was an exercise in translation. After telling a seventh-grader in a Yale sweatshirt she would “let that go for now,” Brownson shared a story tailor-made for middle schoolers. At the away game against Columbia, while walking the smack-talking gauntlet between the locker room and the stadium, Dartmouth players encircled Brownson—not because she couldn’t handle the chatter, but to demonstrate what a team looks like.

I imagined what Teevens saw when he hired Brownson. In his decades of coaching he had surely learned that adversity cultivates a specific brilliance. Now, with Brownson’s first coaching season done and a set of stats that speak their own story—second in the Ivy League, with a 9-1 record, alongside Brownson’s personal record of 40-plus interviews conducted during and after the season—I suspect that Teevens has a renewed sense of the powers of the historical outsider.

Brownson didn’t change my opinion about football; she shifted my sense of Dartmouth. I have at times been weighed down by my connection to a place that has fostered enclaves of masculinity that say, “We are not here for you,” to women, including my daughter during her first visit. Teevens has charted a hopeful pathway. I am lifted by Brownson’s excellence and held aloft by the men who value her work and thrive under her guidance. It’s not a sentence I thought I’d ever write, but now it is part of my story: I am a Dartmouth football fan.

Lisa Turner teaches at the William Penn Charter School in Philadelphia.