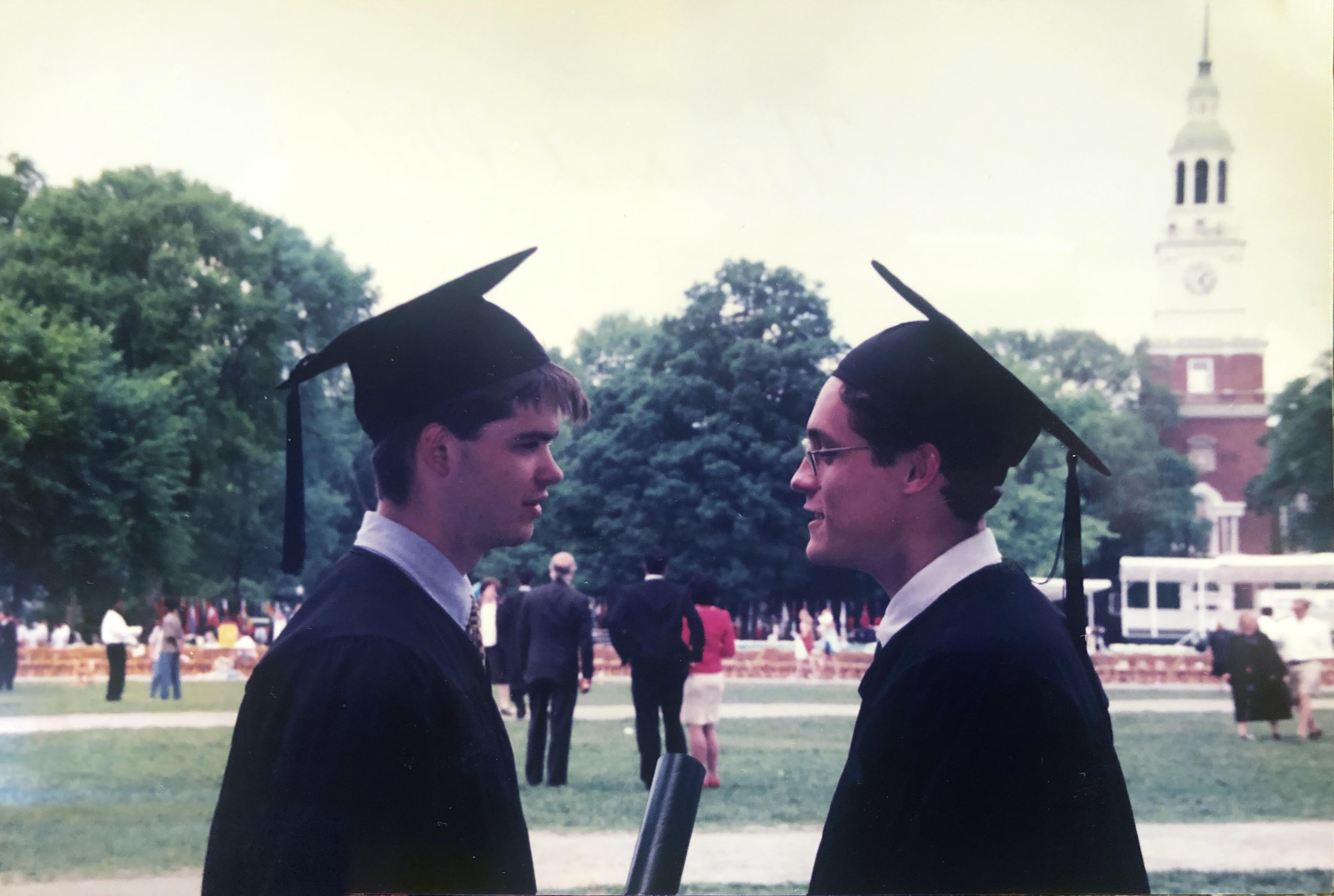

It's Monday, May 20, 2019, and we’re at Hiko Sushi, a strip mall sushi restaurant in Los Angeles, toasting the latest success story in the rise of the Academy-Award-winning filmmaking duo Chris Miller and Phil Lord, members of the Dartmouth class of 1997. In February they won the Best Animated Feature Oscar for producing Sony’s Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, and Sony TV has just signed them to a five-year TV deal. We’re celebrating with saki.

The team’s rise has been as easy to follow as it has been meteoric—creating and showrunning MTV’s Clone High in 2002, writing and producing How I Met Your Mother from 2005-2006, and writing and directing Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs in 2009 with the support of Amy Pascal, chair of the Motion Pictures Group of Sony Pictures Entertainment; 21 Jump Street, 22 Jump Street, The LEGO Movie, and The Last Man On Earth with Will Forte all followed. The only setback came when they were replaced in the midst of filming Solo: A Star Wars Story, a hiccup so inconsequential they won an Oscar for their next project.

Miller, who turns 43 this year, and wife, Robyn Murgio ’97, have two children, Graham and Cora. He’s from Everett, Washington. Lord, 43, is from Miami. He and his girlfriend Irene Neuwirth have two Labradoodles, Teddy and Miguel. Both men drew comic strips for the Daily Dartmouth, though Miller’s Sleazy the Wonder Squirrel was a more regular feature than Lord’s Loud Mouth.

What’s it like to win an Academy Award?

CM: It’s pretty great. We feel very lucky.

PL: It was a very trippy night. Pharrell was there.

Did you think you were going to win?

PL: We wanted to win, but we were prepared to not win. We held hands in a spontaneous expression of brotherly love while they opened the card.

How did you celebrate?

PL: We were at the Vanity Fair party, where I ate an In-and-Out cheeseburger.

CM: We went home around 2:30 in the morning, which was very early for that night.

How would you describe what Lord-Miller films are? What’s your brand?

CM: Well, we don’t like to do things that are bleak or mean-spirited.

PL: Our movies are friendly.

CM: They usually have an optimistic, positive attitude, whether it’s a comedy or not.PL: They’re super cynical, but we’re really optimistic about human beings. We want our movies to break new ground and be surprising, but we also want them to be good for you.

What do you love about the TV and movie business?

CM: It’s amazing that we get to come up with crazy ideas and make them into a reality. It always feels so magical when you think of something and then someone builds a set. We can think of something in our minds and then have it be real. I never get over that. It still makes me giddy.

PL: I’d say it’s the collaboration with all of the crew members, artists, cast, and writers. That thing when everyone is cooperating to make art, which to me is miraculous. It’s miraculous when people get on an airplane in orderly fashion, let alone when they get together to do something as abstract and apparently as meaningless as a film or a TV show.

“It feels so magical when you think of something and then someone builds a set. It still makes me giddy.”

And what’s your least favorite part?

CM: When people start making decisions based on fear. They’re afraid to take risks, and you often end up with a self-fulfilling prophecy. Whenever I run into people who are nervous, that’s the toughest.

PL: When folks don’t put the art and the audience first. We are privileged to make art for a living and lucky to have this platform to communicate with people, and we are doubly lucky because we get to communicate with young people.

Let’s talk about that collaborative effort. How does it work for you guys?

CM: Filmmaking and television are collaborative because nobody makes these things alone. There’s a crew of 100 people, and they all have to be able to see your point of view, your vision. You have to be able to defend it like a dissertation every day, and it’s kind of exhausting, but it ends up being really useful because of all the other filmmakers working with you.

PL: Most of the time we’re in agreement.

CM: Like nine times out of 10, but there are so many decisions that happen in a day that one time out of 10 comes up a lot. We’ve tried writing together in the same room, and it doesn’t work. So what we end up doing is work on an outline together, and then we split up scenes and pass them back and forth until the point where we get kind of passive aggressive with each other. Then we talk out the scene again. It’s a slow, slow process. But it ends up working.

PL: I look to you to tell me if the thing makes any sense.

CM: And I look to you to tell me if it’s inventive and new enough.

PL: But we are both insane.

CM: We each fill any vacuum created. When he does one thing, I do the other thing.

How has your collaboration evolved?

CM: There have been a lot of growing pains. We both were used to being like a boss with the final say of our own film.

PL: We’ve become a lot less precious.

CM: I’m double married. I’m married to my wife, and I’m married to Phil and...

PL: ...We’re stuck together.

CM: The reason this collaboration is successful is because each of us respects and values the other person and what he brings. And we’re each like a life preserver rather than a weight. The second it feels like a nuisance, it’s doomed. At this point we’re doing so many things and spread so thin that we’re each able to run point on things and then have the other one come in and help, and you’re so relieved to have help because you can’t see straight anymore.

PL: Our first 10 years we would have our frustrations, but the work was always better when it was the two of us. It’s just more fun to do it with your buddy, and it’s more interesting to be challenged.

If you guys reach loggerheads, how do you decide?

PL: It’s hard.

CM: What we often will do is bring in a tiebreaker. There are people who we work with that we really trust. Again, when you’re doing these things you’re never alone.

Can you tell us about a disagreement you’ve had?

PL: The best fight?

CM: The famous original one.

PL: Abe Lincoln’s nose.

CM: We each would draw Abe Lincoln, the main character in Clone High, because we were still learning how to be animators. I drew a rounded nose, and Phil drew a square nose, more stylized. I didn’t like his, he didn’t like mine. We kept butting heads.

PL: Yours was probably more accurate.

CM: And you were a bit more radical.

PL: A bit more extreme.

CM: We came up with this phrase, STD: split the difference.

PL: And that’s it.

CM: And we made the nose round and square. It was a square with a little round top.

PL: Everyone was satisfied.

CM: It was a compromise.

How did you end up in Hanover?

PL: I visited Dartmouth in the summer when it was really nice. Everyone seemed really happy there. My mom loved the town. That was basically it.

CM: When I visited, everyone was wearing Dartmouth sweatshirts, and I was like, “Wow, there is a lot of school pride here.” Then I realized it was just because there was just one place in town to buy clothes. [Laughs]

PL: I don’t think that’s true. I liked being in the woods.

CM: Yeah.

You had no Dartmouth connections?

PL: No.

CM: I technically went because I lost an air hockey game to my friend Rory McGee.

PL: Is that true?

CM: I was trying to decide between some schools, and I told her that if I lost to her in air hockey I would go to Dartmouth.

PL: I love that an 18-year-old can make a decision [laughs] about the rest of his life. What a terrible idea. I should have just let my parents pick.

How did you meet?

CM: We had a friend in common who said, “I met someone who is just as weird as you. I think you guys would get along.”

What exactly was weird about you?

PL: I think we were unusually prone to wearing giant bow ties and weird shirts.

Did you have any favorite professors?

CM: Yeah, lots. We had an animation professor in the film department, David Ehrlich, who was very instrumental in pulling us into doing more of that stuff. He became a weird mentor.

PL: He comes from an independent animation background, so his personal work is drawing on tracing velum back lit from underneath. Really lyrical, and...

CM: Rainbowy.

PL: ...Seventies, hippie vibes, and very Vermont.

What were your projects?

CM: Mine was all hand-drawn, based on my comic strip. [View Miller’s animated film here.]

PL: I made a movie called Man Bites Breakfast. It was about a guy whose breakfast cereal turns against him. He magically turns small...

CM: …He eats the breakfast, and the breakfast eats him.

And somehow Disney’s CEO Michael Eisner heard about you?

CM: Apparently, and we’ve only heard this apocryphally, he had read something about us. One of his sons went to Dartmouth.

PL: Eric [’95].

CM: Barry Blumberg, the head of Disney television animation, called me in my off-campus apartment and said, “Hey, I’m from Disney. Do you want to come up for a meeting?” And I was a senior. I said, “No,” because I’m really smart. I said, “I have midterms, I’m too busy. But my friend Phil and I are just finishing up these student films. I’ll send them to you when we’re done, and we’re going to move out there anyway, so maybe to save you a flight, we’ll meet up in July or something.” And they were like, “Well, they’re just playing hard to get, I guess. They must have had lots of offers from others.” I don’t know why I did that.

Then what happened?

CM: I sent him our films on VHS, and then we both moved out to L.A. and had this meeting that was about five minutes long. We sat down, and he was like, “So you guys went to Dartmouth?” And we were like, “Yes.” “And they have a skiway?” “Yes.” “What’s it called?” “The Dartmouth Skiway.” “You got a hockey team?” I’m like, “Yes.” “Are they good?” I’m like, “The women’s team is really good,” and he’s like, “Well, I really loved your films. I can’t wait to work together.” And then he left, but they offered us a development deal as a team to come up with Saturday morning cartoon shows. We were 21, didn’t know what we were doing, and we’d never been actually a team before. We were used to making our own films.

How did things go?

PL: We spent a year developing Saturday morning TV shows. Well, we pitched a bunch of things that were inappropriate for children.

CM: But then at the same time, South Park came out on television, and it became a big phenomenon: animation for adult audiences.

So then came Clone High, your animated show about a high school of famous teenagers: John F. Kennedy, Mahatma Gandhi…

CM: …Joan of Arc, Abe Lincoln, and…

PL: …Cleopatra.

CM: And they date [and act like teenagers].

The show tweaked people like John F. Kennedy, whose clone is a rakish, womanizing, rich boy.

PL: To say the least.

And Gandhi is a partier.

CM: That is correct.

PL: He feels a lot of pressure to live up to his clone father.

CM: The real Gandhi, when he was young, was a party guy. He would go and tell jokes and get drunk and have a great time at parties. And then he went back to India and saw the suffering there.

PL: He really changes his tune, that guy.

CM: So we were just sort of representing the early days of Gandhi.

That sort of thing could ruffle some feathers.

CM: It did ruffle some feathers.

PL: One of the fastest growing parts of MTV was India, where they have about a billion customers. And so the head of Viacom...

CM: ...The parent company of MTV...

PL: ...Finds himself in the MTV India building and someone taps him on the shoulder and says, “Listen, not for nothing, but there’s a pretty serious protest going on outside, and we can’t leave right now.” It was a hunger strike to protest the Gandhi character in our little show. It was also the anniversary of his death.

CM: Exactly. That show went off the air very quickly.

PL: I can’t say we were a ratings champion.

CM: It was only airing in the U.S. and Canada at the time.

Next you got the big break to do Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. How did that happen?

CM: Clone High, our one-season, instant failure show had an underground cult following, including a guy at Sony animation who brought us in. We pitched doing [Cloudy] like a disaster movie, like a Michael Bay movie, but funny on purpose. And they crazily let us do it.

PL: Didn’t we lie and say we had a whole story?

CM: Yes.

What was the lie?

PL: We said, “We’ve got a lot of ideas for that Cloudy thing. What’s going on with it?” They were like, “It’s crazy, we’re about to lose the rights. How quickly could you come in—tomorrow?” We said maybe the day after tomorrow and went to my apartment and overnight came up with the story that is basically the movie that we made.

“We want our movies to break new ground and be surprising, but we also want them to be good for you.”

Can you talk about Amy Pascal, the president of Sony, who had a big influence on you?

PL: The best.

CM: Yes.

PL: During [the creation of] Cloudy, she didn’t like it very much.

CM: It didn’t have an emotional story that you could really hook into. It was just joke after joke after joke. Amy was upset that it didn’t have that aspect.

PL: She was mad at us.

CM: She said, “I want a story.” To her credit, she didn’t fire us. She liked us and thought that we had a unique tone and a voice.

PL: She said, “I like this book, and I like these guys. I hate everything else.”

CM: And so she introduced us to Lindsay Doran, who is sort of a script guru and used to run United Artists back in the day.

Pascal said your story had no emotional anchor.

PL: It’s true. Then she gave us the help we needed. The movie was boring, and we couldn’t figure out why, because every sequence was hilarious.

CM: We had been resisting doing a father-son story for a while, but then we were like, let’s give it a try. And that’s where the emotional storyline of that movie came from.

PL: The whole movie got funnier, too. It was an amazing lesson.

CM: She flipped our thinking, and we became huge proselytizers for trying to make you cry as well as laugh in every single movie we’ve done.

PL: And now we drive people crazy.

CM: Because we want to be as emotional as we can be. If you go to the theater and you feel emotions, you had a good experience. You can say, “I felt something and I’m not dead inside. I feel happy.”

PL: I laughed.

CM: I cried...

PL: I cried.

Do you like film better than television?

PL: No, I like them both. I like the immediacy of television.

CM: A lot of the best original stories are happening in television. There are a lot of ways to tell interesting stories on TV that you can’t quite do in films.

I want to ask you about the only blemish on your unbelievable track record. You were brought on to do Solo, and there were obviously creative differences between you and the Star Wars people.

PL: The character of Han is a maverick, and we were trying to do what we try to do with all of our movies, which is take something that you know and turn it on its ear. We try to do something you’re not expecting. That’s what we tried to do with Spider-Verse. But we didn’t see eye to eye creatively.

CM: Ultimately, it was largely a positive experience for us as filmmakers. I think about all the things we learned, about all the great people we worked with. We had a ton of fun, and we grew, and we’re so proud of that cast and crew.

Do you have any advice for fellow Dartmouth alum David Benioff ’92, who is now doing his own Star Wars series and will have to answer to the same people?

CM: Godspeed and good luck!

You just signed this huge deal with Sony TV.

PL: Yes, we’re moving from 20th Century Television to Sony Television, where they’re making a big investment in us.

What are some of the balls you have in the air?

PL: We’re going to put Marvel characters into TV shows related to the Spider-Man universe. There’s a Spider-Ma’am, who is Aunt May from the comics. There’s Spiders’ Man, a man made up of thousands of spiders.

CM: There are hundreds of these things. And there are villains.

PL: There are some other notions that we haven’t started yet.

And film?

PL: Yes, there’s a lot. We’re developing a feature called Artemis based on a novel by Andy Weir, who wrote The Martian. There’s another movie we’re working on called Last Human.

CM: Plus other television shows we already have going, which includes Bless the Harts, an animated show that’s coming on Fox this fall that has Kristen Wiig and Maya Rudolph. It has some wonderful actors in it. And another animated show called Hoops.

In Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, the lead character is a young boy of color, Miles

Morales. That’s been important to you from the beginning—to represent onscreen what the world looks like today rather than how it was depicted when we were growing up.

CM: Absolutely.

PL: For sure. It was really important to us. We didn’t want to make the movie unless it could be about Miles Morales and have Spanish spoken without translation underneath, like it’s the fabric of some kid’s life.

CM: We wanted to authentically present a bilingual household and reflect the world we all live in.

Can you tell us a good behind-the-scenes story from your movie sets?

CM: On 21 Jump Street, which was our first…

PL: …Live-action feature. Johnny Depp was going to do one day of shooting.

CM: A cameo.

PL: He gets into this whole makeup thing where he is completely unrecognizable. He has a long beard—he looks like ZZ Top. That evening we had a break for a meal, and Johnny disappeared. He came back a couple of hours later and said, “I’m sorry, I was in costume and nobody recognized me. Brie Larson thought I was an extra and asked me, ‘Like, what is this, your first time on a set?’ I realized this is my only chance to ever go down Bourbon Street, so I went in full disguise, and nobody recognized me. Sorry for the delay.”

Do you read the critics?

CM: I do, and he doesn’t.

PL: I read none.

CM: It’s really masochistic, but I can’t help it. We’ve been very lucky, but even so, when there were five bad reviews of Spider-Verse, I’m like, “Hey!”

PL: I think now we have a really thick skin about stuff, and we can laugh a little bit.

Why does the world need comedy and entertainment—your comedy and entertainment?

PL: I grew up with people who believed that art and music were as important as breathing. I guess that caught on with me.

CM: We spend a lot of time thinking about the themes of our projects, what we are trying to say, and asking if this is good for society. Adding jokes and having it be fun and having a positive tone is helpful—life is hard, and it’s nice to have a moment of joy.

Jake Tapper is an anchor and chief Washington correspondent for CNN.