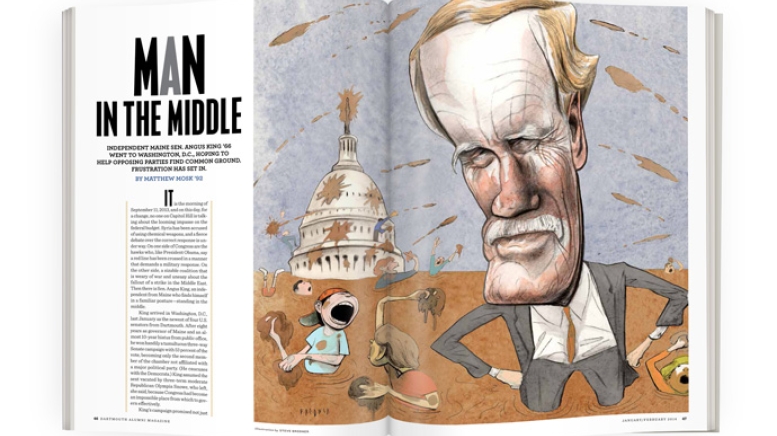

It is the morning of September 11, 2013, and on this day, for a change, no one on Capitol Hill is talking about the looming impasse on the federal budget. Syria has been accused of using chemical weapons, and a fierce debate over the correct response is under way. On one side of Congress are the hawks who, like President Obama, say a red line has been crossed in a manner that demands a military response. On the other side, a sizable coalition that is weary of war and uneasy about the fallout of a strike in the Middle East. Then there is Sen. Angus King, an independent from Maine who finds himself in a familiar posture—standing in the middle.

King arrived in Washington, D.C., last January as the newest of four U.S. senators from Dartmouth. After eight years as governor of Maine and an almost 10-year hiatus from public office, he won handily a tumultuous three-way Senate campaign with 53 percent of the vote, becoming only the second member of the chamber not affiliated with a major political party. (He caucuses with the Democrats.) King assumed the seat vacated by three-term moderate Republican Olympia Snowe, who left, she said, because Congress had become an impossible place from which to govern effectively.

King’s campaign promised not just a moderate, business-friendly agenda that was left-leaning on social issues but also to do what Snowe considered impossible: provide a bridge between the increasingly factionalized parties to get things done. “He’s independent and a problem solver,” actor Sam Waterston ofLaw & Order said in a television ad for King that aired in the closing weeks of the campaign. “I think they’re afraid of Angus in Washington, which might be the best reason to send him there.”

Today King is in his office suite for a weekly open house. Tall and lean, with the ruddy, stiff-jawed look of a Maine lobsterman, King smiles warmly as a staff member snaps photographs of the senator with organic dairy producers and members of the New England Farmers Union. A Los Angeles Times reporter briefly corners King in his conference room. The Syria question was the first one keeping him up at night since he took office, King says. “I am trying to learn as much as I can to understand the ramifications of this question, which are enormous,” he says. “Is there more risk to the national interest in doing nothing, or is there more risk to the national interest in acting?”

With the help of his staff King ends the interview quickly and returns his attention to the dairy farmers. The Syria question would resolve itself before King was forced to take a firm stance, and in a matter of days focus would be back on the issue that has most stymied Washington in recent times: the budget. Across the Capitol complex in the House, the first rumblings are emerging that a government shutdown is looming. In part because of the deep divisions it would emphasize, the shutdown would present an enormous opportunity for King. It could become the first test of his desire to snuff out gridlock and dysfunction.

The Real Thing

King’s childhood in the northern Virginia suburbs of Washington offers few clues to his political leanings. He describes his parents as Roosevelt Democrats but says he grew up a fan of President Eisenhower. King applied to Dartmouth, sight unseen, because between his junior and senior years in high school his sister married Dartmouth alum Jim Neff ’59, “and I liked the guys at the wedding,” he says. King’s interest in politics was immediate. He recalls, in detail, the lectures of longtime Dartmouth government professor Vincent Starzinger. “I remember him using the movie The African Queen to explain the two different views of natural law,” King says. “Humphrey Bogart wakes up in the boat to see Katharine Hepburn dumping his gin out into the river, and he’s very upset. He says to Hepburn, ‘It’s only natural, ma’am, that a man should want to drink every now and then.’ That’s one view of natural law. Hepburn said, ‘Nature, Mr. Allnut, is what we are here to rise above.’ That’s the other view of natural law. It has been 50 years and I remember every word of that lecture.”

Larry K. Smith, a former Dartmouth history professor now retired after a career in Washington, remembers “Gus” in “History 56,” the political history of the United States since 1864. The class, which was a study in power and how it’s used politically, Smith says, attracted ambitious students. When political discussions would get going, “you could feel the heat in the room,” he recalls. King stood out: “For all of his prestige on campus, you never got the sense that he was a politician of any sort. And yet he was clearly recognized to be the class of his class. He carried himself with such ease and grace.”

Despite his clear interest in politics, King’s involvement was largely as an observer. He worked at WDCR and traveled in 1964 to New York City to broadcast results from the Goldwater-Johnson election. “We were part of a national college radio election-night program, and it was like our own NBC,” King says. “We got results. I was a commentator, talking about who was winning and who was losing and what it meant.” A year earlier, Dartmouth students had learned of the Kennedy assassination listening to WDCR. They heard the news from King, who broke into a music program to report as the day’s events came over a teletype machine. (King says he carried the printout announcing Kennedy’s death in his wallet for decades until it finally crumbled into pieces.)

The radio job helped prepare King for the career he forged after law school and a brief stint on Capitol Hill with Maine’s Democratic Sen. William Hathaway—as a television interviewer and commentator on the public broadcast affiliate in Maine. He moved from there into the alternative energy industry. It was from this business perch that King followed a path into politics as an independent. Throughout his tenure as governor King’s approval numbers in statewide polls never dipped below 50 percent. Still, competing views formed about him. One Maine Republican—a Dartmouth alum who previously worked in government—agreed to provide his view of King in a series of emails on the condition he not be identified. He says, “King seems the ultimate ‘hail fellow well met’ with the balm of an aphorism for every situation, even if he has never seen it before…and really knows little about it.” The GOP critic says he considers King “a faux independent,” a Democrat who does not want to admit his leanings.

Others, including his early mentor Smith, say the politician’s independence comes from deep within. “People will use the rhetoric of being a moderate and it’s crap,” says Smith. “With Gus it’s a real thing. There are phony moderates or phony independents who are often unwilling to take positions. Gus takes positions and does so as a matter of conviction. It just happens that his convictions don’t fit neatly into either party. Fortunately for him, he comes from a state that enables him to run as that person.”

King says that when he arrived in Washington he knew there would be doubts about him on both sides of the aisle. When he first approached Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) to talk about his ideas on regulatory reform, King says he expected skepticism. At that point he was known only as the man the National Republican Senatorial Committee spent $1.2 million trying to defeat in 2012. “I’m sitting with Roy telling him my views on regulatory reform,” King says, “and I could see his expression change, like, ‘This isn’t the guy I thought he was. Why did we spend a million dollars to kill this guy?’ ”

An Issue That Resonates

King’s first real foray into the murky political waters of the U.S. Senate came almost by accident. It was May of 2013 and a member of his staff had flagged one of the Senate’s many looming deadlines: Without congressional action the interest rate on federally subsidized Stafford student loans was poised to double on July 1 from 3.4 percent to 6.8 percent. “It seemed to fit philosophically with some of the things that the senator has taken issue with down here, these sort of artificial deadlines, lurching from year to year, without really coming up with long-term, sustainable solutions,” one King staffer explains.

In many ways the student loan issue presented an ideal political opportunity for King. On one side were liberal Democrats led by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), who believed the government should support a subsidized loan program that would greatly relieve the financial burden facing college students, even if it came with a hefty price tag. On the other side were Republicans whose proposal, very similar to Obama’s, was for a market-based loan program that operated much like traditional loans, giving students competitive borrowing rates while possibly turning a profit. King and a small coalition of senators including Sen. Richard Burr (R-N.C.) and Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.) decided they would try to create a revenue-neutral program that fell somewhere between the rival versions.

In June, when senators were presented with votes on the Democratic and Republican versions of the student loan bill, King and Manchin broke ranks and voted against both of them. King released a statement to the press saying he believed “that we can bridge the differences between the competing proposals to reach a compromise solution that can acquire wide support. We just need to set the politics aside and do the work.”

The rogue group of senators drafted its proposal and introduced it in late June, just days before the loan rates would double. At first their attempts to bring more senators on board met with resistance. Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), the powerful committee chairman who oversaw education issues, was not happy with their proposal. A number of Republicans were also skeptical that rates could be brought down without costing the federal government. As the deadline passed, a second attempt was made to bring the Democratic plan to the floor for a vote, but it again fell short. Once that failed, the president got involved.

King, along with Manchin and Sen. Richard Durbin (D-Ill.) were summoned to the White House, where they found Harkin and Burr waiting with Obama. The goal was to broker a compromise bill. “The president wanted this off his plate,” King’s staffer explains. After the meeting the number of senators willing to vote for the King-Manchin bill started to rise. During the course of several weeks King tried to keep an accurate count of his bill’s support, but it was tough. Every time he would shave off a section to bring more Democrats on board, he risked losing support from Republicans.

When the date for the vote finally came, King’s staff had calculated they had just barely enough support for the measure to pass. When the vote got under way, Durbin, whose job as Senate majority whip is to muster and keep count of votes, walked up to King on the floor and handed him a small scrap of paper. It had a number on it: “74”—a projected tally of “aye” votes. The bill, King realized then, was going to pass.

King was near the center of a group of Republicans and Democrats hovering over Obama on August 9 as the president prepared to sign the bill into law. The president praised the “extraordinary coalition” that had led to the passage of the compromise bill, then noted wryly, “It feels good signing bills. I haven’t done this in a while. Hint, hint. Hint, hint.”

Shutdown

The government shutdown has been under way for two days and back in a plush Senate conference room King is speaking to representatives from a group of Maine credit unions who stopped in to visit him that day. He is offering his take on the Tea Party’s budget maneuvers: “I remember in college we heard a great way to make money. Do you know the story about how to make money with a cocker spaniel and a gun? You put a picture up that says, send $10 or I shoot the dog,” King smiles. “I didn’t say that, did I?”

Back in his office King explains that he has given deep thought to this impasse and its causes. Because of the way congressional districts have been drawn, members of Congress for the most part occupy safe seats—until they are threatened by primary opponents from the most orthodox wings of their parties. “We can have broad national consensus that this shutdown is a bad idea, and it’s not going to affect an individual member as he or she looks to their district in Louisiana or Tennessee or Idaho or wherever it is. If that Republican electorate is fired up and wants to kill Obamacare or shut down the government, there’s no political incentive for that person to sit down and talk,” King says. “That’s dangerous.”

More than that, King has fixed his concern on what he sees as a new and dangerous approach to legislating that he believes Tea Party Republicans are employing. He pulls out a paper that he says contains a list of demands House Republicans have made in order to get them to pass a budget and reopen the government. He rattles them off, growing increasingly incredulous with each alleged demand.

“This small group in the House is trying to create a new way of legislating that’s not in the Constitution,” King protests. “You legislate by passing a bill through the House, passing it through the Senate and sending it to the president. They’re saying, ‘We don’t have the votes to do that, therefore we’re going to grab the entire U.S. government or the credit of the entire U.S. government and say we won’t do anything unless you legislate what we want—unless you agree to what we want.’ That’s not the way the system was designed.”

King insists he is not ready to give up. He has, for instance, joined a group of moderate House and Senate members who began meeting in hopes of cobbling together a budget document both sides could live with. He has also joined a group of 14 senators formed by his Maine colleague, Republican Sen. Susan Collins, to try to piece together a deal.

“Right now is a moment of maximum frustration,” he says. “My whole deal is trying to find common ground and find solutions. What’s holding me up is that I don’t know if you want to find common ground in a situation where you’re being held hostage. If you do, this will be the routine way we’ll do business around here.

“It goes against my basic orientation of trying to find solutions,” he says. It is inescapable, King realizes now, that the nation’s capital is different than it was 40 years ago, when he first came to town as a Senate staffer. In 1973, he says, there were probably 20 senators who overlapped ideologically—moderate Republicans who were arguably more liberal than conservative Democrats. “Now there are literally none,” King says.

The 2013 federal government shutdown lasts for 16 days and, according to the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, it is expected to have cost the U.S. economy between $2 and $6 billion in economic output. It is resolved not by diplomacy from moderate politicians looking to broker an agreement, but by wrenching public pressure and a short-term fix of the sort King has publicly protested.

A month has passed when King, brimming with good cheer, arrives in the sleek television studio that is hidden away in the basement of the Capitol Visitor Center. Bright theater lights hang from the ceiling and a variety of sets include a fireplace, a Christmas tree with wrapped presents and a modern-looking TV news desk. King takes a seat in front of what appear to be French doors and an American flag. He is about to hold a 45-minute Skype conversation with social studies students at Mt. Ararat High School back home in Maine. The father of five is jovial and at ease. Such talks, which he calls “Capitol Class with Angus,” are a staple of King’s tenure.

He explains to the students that, as a member of a committee tasked with finding solutions to the problems that led to the shutdown, he sits at the center of negotiations to develop a budget. “We had our first meeting last week,” he says. “There are a lot of behind-the-scenes negotiations going on now as we try to arrive at an agreement that will make everyone equally unhappy, I guess is the best way to put it.”

Students then rotate into a seat in front of the camera to ask how he juggles his work and personal life, whether he plans to seek reelection and what he considers his greatest challenges. A student named Emma takes the seat and asks King what it means for him to be an independent in Washington.

“It gives me the opportunity to work across the aisle and try to find solutions,” he continues. “It was amazing when I first got here and I went around meeting senators. A number of them said, sort of almost under their breath, ‘Boy, you’re in just the right place.’ They really liked the idea that I could try to build bridges, and in fact that’s what we’ve tried to do.”

King tempered that sunny view from the center shortly after the Skype conversation ended and he headed back to business. “I’m very optimistic that the partisanship can be overcome when the challenge is a small- or intermediate-sized issue,” he says, hearkening back to his experience with the student loan legislation. “But on the big issues…,” he pauses. “I’ll be honest with you, on the big issues I’m just not so optimistic.”

Matthew Mosk, an Emmy-winning investigative reporter for ABC News in Washington, D.C., lives in Annapolis, Maryland.