“Welcome to ‘English 5.’ ” A small smile lit professor Elizabeth Ermarth’s face, suggesting a deeper meaning than her words conveyed. In the innocence of my youth, however, I ignored any instinct to run, took my seat in Sanborn House, and flipped open my lined spiral notebook.

In 1973 every student at Dartmouth was required to take “English 5,” preferably as a freshman. Having a profound fear of writing, I figured I would be less stressed if I took the course in the fall term to get it out of the way. It was the first class I attended and seemed tame until Ermarth closed her book at the end of class and said, “Your first assignment, due Monday, is to write a five-page paper on the first four books of Paradise Lost.”

Have you ever read Paradise Lost? Not an easy thing to decipher, much less inspire a five-page paper. It turned out that we had to write one paper each week. The good news was that if we didn’t like the grade we received, we had the option to rewrite the paper—as many times as we desired. The only grade that would count would be the one on the last version submitted.

Although I was anxious about the volume of writing, this sounded feasible to my virgin, 17-year-old ears. I spent the next few days deciphering the first four books of Paradise Lost, wrote my paper, and called home to tell my folks all was well.

And it was, until I got back the graded paper. It was covered in ink. Every sentence was edited and had arrows to comments such as “Lack of definition throughout,” “Wrong word choice,” and “This makes no sense.”

I got a D+. This was not the way I planned to start my college career.

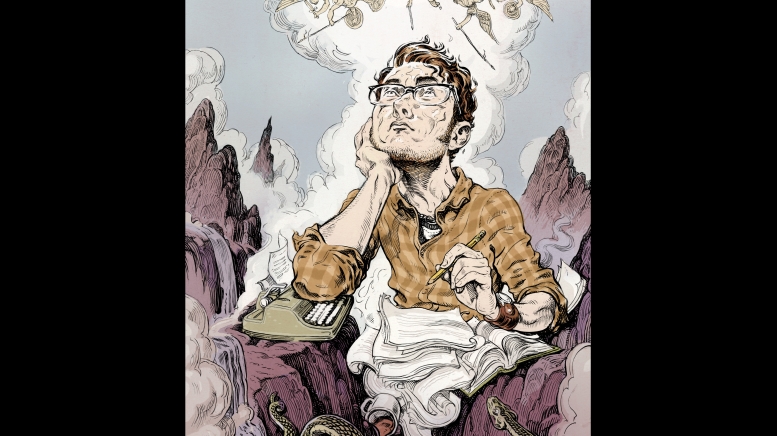

Like an infernal machine, the papers kept coming. I was writing or rewriting a paper every night.

In despair, I took solace knowing others had received similar grades. I also knew I could rewrite the paper to get a better grade. I already had another paper due, however, and from Ermarth’s comments on the first one, it was clear the second paper wouldn’t fare much better than its predecessor. To make matters worse, in those days we had to type everything on typewriters that had no self-correcting features. (We used Liquid Paper to cover our mistakes.) I put in a few late nights to catch up.

I got a C- on the rewrite and no grade on the second paper. Ermarth wrote me this note:

“What’s on the pages seems much ado about a small point, namely that the form of the work is a device to involve the reader. This is true of any work in any language, and so in effect you say nothing in saying this. The language isn’t bad, considering how hard it is to write well without an argument to develop…much of your argument here is merely assertion, which of course is no argument at all.”

We had been given an opportunity to suggest our own grade. I had given myself a B-. Ermarth’s conclusion was sobering: “Your evaluation seems optimistic.”

I called home in a panic. I was in over my head. Even after my dad’s pep talk—“They wouldn’t have let you in if they didn’t think you could do the work”—I wasn’t so sure.

I went back to writing. Now I had to do a third new paper and complete two rewrites. I began to think Ermarth was sadistic—until I realized she had to grade every paper we submitted. Okay, I figured, maybe she was a masochist, too.

Like an infernal machine, the papers kept coming. I got to the point where I was writing or rewriting and typing a paper every night. I never had gotten a C before in my life. Now I was relieved to get a C+ on any first draft.

I rewrote the Lost paper four times (for an A-/B+, thank you). I rewrote one on Camus’ The Fall three times and was relieved to get away with a gracious C+. Never choose an existentialist subject with an English professor.

Needless to say, “English 5” did nothing to cure my fear of writing. After 10 weeks of sweating over paper after paper, I ended the term with an exhausting B+. After that, I avoided any class that required lengthy papers. As a history major, that was hard to do.

Sadly, “English 5” was one of the last classes Professor Ermarth, then an adjunct assistant professor and wife of professor Hans Ermarth, would teach at Dartmouth. She would go on to publish several books and become a senior Fulbright fellow at Cambridge University and Saintsbury Professor at the University of Edinburgh.

It was also the last English class I took at Dartmouth. I now consider this an enormous personal loss. Dartmouth has always had some of the finest English professors on the planet, including Ermarth. I was foolish and cowardly to pass them by.

I’m still afraid of writing. The blank page is no friend of mine. The odd thing is I did learn to write in “English 5.” I came to value short, clear sentences that worked together to become short, clear paragraphs. I became addicted to the cadence of words and the allure of alliteration. I love a good story arc and characters who speak their minds rather than the words I put in their mouths.

I could not have imagined then, during those early-autumn walks to class in Sanborn House, that I would wind up writing for a living, but somewhere in the back of my mind, I must have had my suspicions. There are only four files from my Dartmouth days still in my writing desk. Ermarth’s edits of my “English 5” papers are in one of them.

Joe Gleason is a public relations consultant. He lives in Clifton, Virginia.