North of Ar Rifa, we spotted the battalion’s fireflies flashing in a field east of the highway and silently rolled into the perimeter. While the platoon prepared for the long drive to Qalat Sukkar, Gunny Wynn and I sat in on a brief of the night’s mission. I was reaching a numbed equilibrium where nothing fazed me. In the past 12 hours I had been shot at by other Marines, overseen the killing of a group of men intent on killing us, watched artillery pour into a crowded town, nearly been killed by my own commanding officer, and now was about to be launched on a long-range mission into enemy territory.

The colonel pulled his officers and staff noncommmissioned officers into a tight circle and rasped through the plan. The British Parachute Regiment would assault the Iraqi military airfield at Qalat Sukkar the next morning in order to use it as a staging base for the push to Baghdad. We would do reconnaissance on the field before the attack. There were reports of tanks and antiaircraft guns there that posed a significant threat to the British force. No more details were given. We’d be racing sunrise and had to leave immediately to be of any use to the assault force. A platoon commander in the back asked the colonel if he had ever seen a movie called They Were Expendable.

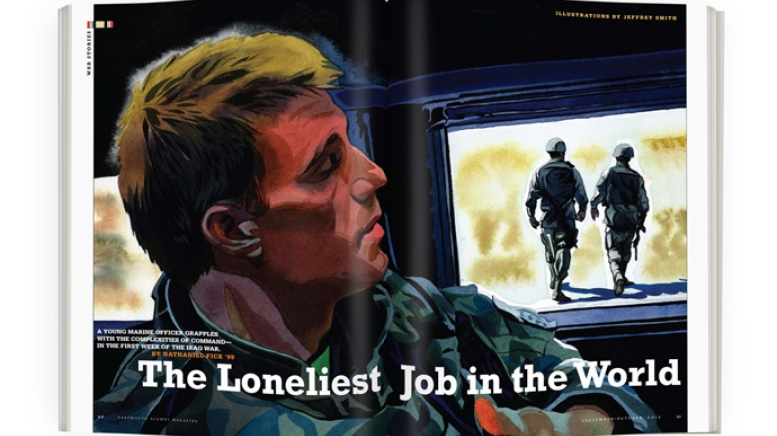

I drove the first leg of the trip, allowing Wynn to catch a bit of much-needed rest. Night-vision goggles restricted my sight to two narrow fields of grainy green. Ahead of me, Espera’s Humvee wove up the highway, its driver clearly struggling as I was. Colbert and Lovell carried the thermal sights at the front and rear of the platoon. Routine banter crackled back and forth on the radio as possible targets were identified and then dismissed as sheep, goats or early-rising farmers. We were exhausted.

We left Highway 7 south of Qalat Sukkar to circumvent the town on empty country roads. For two hours we crept through the darkness. I was taking limited cues—a glimpse of a house or the condition of the road—and building a story around them: population density, terrain, the likelihood of the Iraqi army being nearby. It occurred to me that my impressions could be completely wrong, that I could drive that route in daylight and make entirely different assumptions. Our assumptions governed our responses—whether to attack or withdraw if we got hit, whether to respond with massive force or precision fire, whether to call for reinforcements. I figured I was getting half my assumptions right. The thought was chilling. Fatigue, darkness, stress and a vague mission conspired to envelop us in a fog. Emotionally, I felt as if we were driving a hundred miles an hour down a highway in a blinding snowstorm.

Each roadside ditch and clump of trees was a potential ambush point, and I caught glimpses of alert Marines in the dim glow of GPS receivers and radio lights. The terrain opened up as we neared the airfield, and the clouds dissipated, unveiling a sky of shining stars. Just before dawn, in the coldest part of the night, we stopped and draped camouflage netting over our vehicles. Everyone but those pulling security collapsed into sleep, and I went in search of company headquarters to ask about our next move. The captain said that two foot patrols would be sent out to look at the airfield, but we were not included. I expected that the patrols would observe the field, confirm or deny the reports of significant defenses, and then pull back as we watched the British attack at first light. There was nothing more for me to do, so I returned to the platoon, inspected the lines and stretched out in the tall grass to sleep.

Christeson woke me 20 minutes later. “Sir, we’re getting ready to move.” The eastern sky was already turning pink. Dew had soaked my poncho liner. I threw it in the back of the Humvee. My mouth was dry and my eyes burned with the irritation of too many hours awake. I felt clumsy and disoriented as I joined the captain for an update.

The patrols were still not in position to see the field, but the division wouldn’t authorize the British attack without some idea of Qalat Sukkar’s defenses. I had visions of burning British helicopters falling from the sky and nodded in agreement. It would have been easy, I thought, to delay the attack and use the daylight to do a thorough reconnaissance of the airfield. The morning was clear. We could stack aircraft overhead to obliterate anything that threatened us. But the commanders ordered that we, in our light-skinned Humvees and with no preparation time, would attack the airfield immediately.

I had first felt fear in Iraq on the initial drive into Nasiriyah. The next three days of gunfights had hardly affected me. Hearing that we were about to seize the airfield, I was afraid for the second time. The fear this time was not of Iraqi defenders and my own violent death. Instead, it came from realizing that my commanders also felt the effects of fatigue and stress. Fear filled the little cracks and growing voids in the trust I had placed in them. Remembering one general’s insistence that we train to survive the first five days in combat, I thought how ironic it would be to die on this morning of the sixth day.

Coupled with the fear were resignation and helplessness. I was a Marine. I would salute and follow orders. Without knowing the big picture, we had to trust that they made sense. My Marines and I were willing to give our lives, but we preferred not to do so cheaply. The fear was a realization that my exchange rate wasn’t the only one being consulted.

Engines were already cranking as I briefed the platoon. My operations order took 30 seconds. We’d rush down the airfield’s main access road and crash through the front gate. Once inside we’d do a starburst, with Bravo Company continuing straight ahead, Third Platoon on the left and Second on the right. Alpha and Charlie would break off in different directions. We’d advance across the field and engage any Iraqi forces we found. Consolidation would be on the main runway once we overwhelmed any resistance. Air Force aircraft would be overhead, but their call signs and contact frequencies were unknown. Part of me expected open revolt, but the team leaders nodded, loaded their teams and formed up to move.

Backlit by the rising sun, we raced down the airfield access road. I looked to my right and saw one of the night’s foot patrols facing us with crossed arms raised, our signal for “friendly—don’t shoot me.” The road was several kilometers long, lined with brush and small trees. It looked as though we were alone.

Gunny Wynn drove, and I juggled my rifle and two radios in the passenger seat. Just seconds before we reached the chainlink fence surrounding the airfield, a warning from company headquarters went out to all vehicles: “All personnel on the airfield are declared hostile. I say again, all personnel on the airfield are declared hostile.”

We normally operated within certain constraints. We could respond proportionally in self-defense—“fire if fired upon”—or we could shoot first at obvious military targets. Both categories depended on the target being a clear and present danger. “Declared hostile” meant there were no rules of engagement. It meant shoot first and ask questions later. During training we had learned about Vietnam’s free-fire zones. They had been, it was acknowledged, immoral and counterproductive. Qalat Sukkar was being declared a free-fire zone.

I clicked the transmit button on my radio handset to countermand the order. I wanted to tell the platoon to hold fast to our normal rules of engagement. But I stopped. I thought that maybe the battalion or the company had access to other information they had no time to share. I trusted that making the “declared hostile” call would save my Marines’ lives when they ran into that unknown threat by shaving crucial nanoseconds from their response time. I let the order stand and shouldered my rifle, pointing it at the landscape flashing past.

A machine gun in front of us fired a short burst. I caught a blurred glimpse of people, cars and camels running through the brush. Men carried long sticks, maybe rifles. A garbled radio transmission warned of “muzzle flashes…men with rifles.” Something near the people flashed, but we were already beyond them, sprinting for the runway. We crossed a tarmac inside the fence line and saw guard towers lining the field’s perimeter. Gunny Wynn and I broke to the right, leading the platoon across our side of the airfield. We surged over berms and irrigation ditches, straining to reach the runway and its promise of fast driving. An Air Force A-10 Thunderbolt attack jet stood on a wingtip, its pilot looking down at us. He flashed over so low I could smell his exhaust. I hoped he saw the bright pink air panel on our hood.

We reached the runway and deployed in a semicircle to protect the battalion’s flank as other platoons pressed forward to investigate the airfield’s buildings. Reports of tanks and guns in the trees flooded the radio. We saw nothing.

As the sun rose higher, I took stock of our new conquest. A single cratered runway bisected the field. Grass grew forlornly from cracks in the pavement. A few hangars and other buildings lined the fence on the far side of the field, but there wasn’t a single sign of human activity. The A-10 made one final pass before departing to the south.

Qalat Sukkar airfield was deserted. It looked as if it hadn’t been used in years. High command canceled the British assault since First Recon had already seized the field. The battalion moved to a large pasture north of the airfield and halted. My platoon was assigned 500 meters along the L bend of an irrigation canal. We parked the Humvees at hundred-meter intervals and began digging in. I didn’t know whether we would be here for an hour or a week.

The numbness returned. We had been lucky—again. Disaster was averted not by our own skill, but by Iraqi ineptitude. One well-camouflaged tank on that airfield could have blown up our whole platoon before the A-10 got it. I swung my pickax into the cracked earth. The Marines knew the airfield mission could have been disastrous. There had already been open talk about their welfare being ignored. I had disagreed. The best way to get everyone home alive would be to win quickly and decisively. My thoughts were jumbled as I continued to dig. Ideas and connections were coming together, but below the level of conscious thought.

The Marines thought that the colonel was cavalier, that he sent them on missions with more regard for his career than for his men. Again, I disagreed. Command is a mask. A leader can agonize behind it, should agonize behind it. I knew I did. I suspected the colonel did, too, but he couldn’t show it.

Movement in the distance caught my attention, and I stood up straight, leaning on the pick and craning my head to see. In front of Lovell’s team, five people shuffled toward us. Two Marines advanced on them, weapons ready. I slid into my body armor and followed. As I got closer I could see that two women were dragging an object wrapped in blankets. Behind them, three men pulled another bundle. All through Iraq, villagers approached us seeking medicine for their ailments, but this seemed different. I quickened my pace and saw Doc Bryan, with a medical kit slung over his shoulder, jogging toward the Iraqis, still a football field away from me. I began to run.

By the time I reached them Bryan had unwrapped the bundles, revealing two young boys, both in their teens. Brothers. The older one had a bullet wound in his leg. Coagulated blood crusted his calf and ankle. I saw the younger boy’s face before I saw his wound. Pale green wax. The color revealed how much life had already seeped from the four holes in his abdomen. The boys’ mother and grandmother hovered over them. A few steps away stood the boys’ father. They betrayed no emotion.

Bryan inspected the wounds for a few seconds and announced they were from 5.56 mm rounds. The only such rounds in Iraq were American, and the only Americans there were us. In horror, I thought back to our assault on the airfield a few hours before. The pieces fell into place. Those weren’t rifles we had seen but shepherds’ canes, not muzzle flashes but the sun reflecting on a windshield. The running camels belonged to these boys. We’d shot two children.

The platoon jumped into action. Two teams took over security, while Doc Bryan went to work on the boys. He triaged them and turned to the gut shots first. Tearing open his med kit, he grabbed IVs and saline bags, blankets, scissors and gauze. I reached down to help, recoiling unconsciously as blood seeped into my gloves, turning the green to black. The urge to help was overwhelming. This couldn’t happen. I had to make it right. Bryan was gentle in reminding me that I could be more useful in other ways.

“Sir, we have this under control. Can you get Dr. Aubin over here and try to get an aerial casevac [casualty evacuation]? Tell ’em we have an ‘urgent surgical.’ ”

I expected everyone else to feel the same urgency we felt, but I was wrong. I ran into company headquarters, breathless, and explained what had happened. The captain simply said that a decision to help the kids was above his head. There was no time to fight with him. I moved on. Major Benelli sat in the shade of the battalion headquarters tent, digging at an MRE.

“Sir, I have two wounded children in my lines. We shot them during the assault this morning. My corpsman’s doing what he can, but one of them’s an urgent surgical.”

He shrugged. “So?”

I explained again that we had led the attack just after the call that all personnel on the field were declared hostile. We had seen people. Flashes, maybe rifles, and had fired. But they weren’t soldiers. We had shot two kids, and now at least one of them was bleeding to death in front of my platoon.

“The colonel’s asleep. Just tell them to go back to their house. We can’t help them.” He went back to his food, dismissing me.

My vision narrowed to a tunnel. There was no clean, clinical explanation for what I felt and what I wanted to do. I wanted to tell the major that we were Americans, that Americans don’t shoot kids and let them die, that men in my platoon had to be able to look themselves in the mirror for the rest of their lives. I wanted him to get out there and put his hands in the kid’s chest to stop the blood that flowed in rhythmic spurts from the holes. I wanted to cradle the major’s head between my arms and twist.

But there wasn’t time. I was still conditioned to accept senior officers’ decisions, regardless of their stupidity, criminality or inhumanity. So I walked away and found the battalion medical officer, Navy Lt. Alex Aubin. I briefed him quickly. Aubin’s eyes were wide. He grabbed his equipment and went to join Doc Bryan while I returned to battalion headquarters. We still needed permission to evacuate the boys, and I couldn’t do that on my own. Benelli smirked when I approached.

“The colonel’s still asleep, lieutenant. I’m not waking him and I’m not endangering Americans to evacuate those casualties. Deal with it.”

Those cracks in my trust were getting wider, growing into chasms, filling with fear and rage, sorrow and regret. I felt impotent, but I wasn’t powerless. I had an assault rifle in my hands. I could shoot the mother******. I could hold him hostage until he called in that helicopter. There was just enough cool self-awareness left in my mind to stop me. This was one of those times I’d been told I’d face. After all that training, all the ego inflating and power tripping that went with being a Marine, this was it. My very own leadership challenge. I drove back to the platoon.

Our values were being inverted, and it threatened to destroy us. Good Marines were sent on a stupid mission governed by harebrained rules of engagement, and now they were being abandoned to suffer the consequences of other people’s poor decisions. I thought of the untold innocent civilians who must have been killed by artillery and air strikes during the past week. The only difference was that we hadn’t stuck around to see the effects those wrought. Our actions were being thrust in our faces, and the chain of command was passing the buck to the youngest, and most vulnerable, of the troops.

I hadn’t been seized by a sudden burst of conscience. Pro-war. Anti-war. War for freedom. War for oil. Philosophical disputes were a luxury I could not enjoy. War was what I had. We didn’t vote for it, authorize it or declare it. We just had to fight it. And fighting it, for me, meant two things: winning and getting my men home alive. Alive, though, set the bar too low. I had to get them home physically and psychologically intact. They had to know that, whether or not they supported the larger war, they had fought their little piece of it with honor and had retained their humanity. If they got killed or went insane, I had to be able to look at their mothers and explain that they hadn’t been victims of their own comrades’ mistakes. Those Iraqi boys could die, but I couldn’t let them die in our hands.

Doc Bryan looked up expectantly as I approached. He and Dr. Aubin had stabilized the boys but made it clear that the younger one would die without immediate surgery. The older child would probably linger on for a few days before infection killed him. Team One leader, Sgt. Brad Colbert, stood there, with tears in his eyes.

I pulled Aubin aside. “Sir, the battalion says these kids can get f*****. They want us to let them die. What are the rules if you take control of a casualty?”

There was our escape. Once the battalion medical officer had control of wounded civilians, we were legally and ethically obligated to give them all available care. We gathered eight stretcher-bearers and struck out, on foot, across the field to battalion headquarters.

“Here you go, sir. You want to let them die, they can die right here in front of your tent.” Doc Bryan gingerly lowered the stretcher in front of Major Benelli, who, for once, had nothing to say. Faced with a small-scale mutiny and the growing realization that posterity would frown on Marine officers who sat by while children died of Marine-inflicted gunshot wounds, he slipped around the back of the tent to wake the colonel.

The colonel ordered the boys’ immediate evacuation to RCT-1’s field hospital, where they would be treated by a shock-trauma platoon. Doc Bryan rode along with them to maintain continuity of care until they were turned over to the surgeons. I walked back to the platoon, trying to think of what I could tell my men.

Gunny Wynn and I spent the afternoon cleaning our weapons. I sat in the sunlight next to the Humvee and took off my boots for the first time in two days. My feet were white and shriveled. They smelled like something between cheese and roadkill. I spread a dirty rag in my lap and pulled my M-16 apart. First I wiped down the receiver with oil and set it aside, then I popped off the plastic hand guards and cleaned the barrel with the rag. I punched a cotton swab down through the chamber; it emerged black with carbon. Tapping the bullets from each magazine, I wiped the dust and grit from every round and then stretched and cleaned the magazine springs. Staff Sgt. Keith Marine had taught me that most weapon failures were due to problems with the magazines. After reassembling the rifle, I pulled my Beretta from its holster and unloaded it. Racking the slide to the rear, I took it apart, laying the pieces in my lap. One by one, I cleaned them, turning them over in my hands and watching the sun glint off the dull blue steel. There was comfort in doing this; it gave me time to think without appearing to daydream.

When Doc Bryan returned I called the Marines together. Platoons are families. In the worst platoons, the Marines love one another. But in the best, they also like one another. We had one of the best. I couldn’t bear to see it destroyed. Conflict and disagreement had to be aired or they would fester, simmering below the surface and corroding the relationships on which our combat effectiveness was built. We had to talk about what had happened. I had to be a psychiatrist, coach and father without anyone suspecting I was anything but a platoon commander.

“Fellas, today was f*****-up, completely insane. But we can’t control the missions we get, only how we execute them,” I said. I explained that the battalion had an obligation to Gen. Mattis, an obligation to provide him with options instead of excuses. We were at war, and a different set of rules applied. There was no way to eliminate all the risks, either to ourselves or the people around us.

“I failed you this morning by allowing that ‘declared hostile’ call to stand. My failure put you in an impossible position.” Tragic as it was, shooting the two boys had been entirely within the rules of engagement as they had been given to us. There would be no command investigation into what had happened. Investigations exist in a narrow sense to assign blame, but they also serve to propagate lessons learned. I tried to draw out those lessons for the platoon.

“First, we made a mistake this morning,” I said. Technical details aside, we were U.S. Marines, and Marines are professional warriors fighting for the greatest democracy in the world. We don’t shoot kids. When we do, we acknowledge the tragedy and learn from it. Unfortunately, I didn’t think it was the last time we’d have to make those kinds of decisions.

“Second, I need you to compartmentalize today.” I told the guys to tuck the experience away in their brains, way back there with their wives and their girlfriends and their dogs. It wouldn’t help them survive tomorrow. I needed every one of them to learn from it—and put it away.

“Third, no second-guessing and armchair-quarterbacking.” We made fast decisions all the time. Sometimes we were right and sometimes we were wrong. We couldn’t hesitate tomorrow because of a mistake today. That could get us killed. Come what may, we were a team and we’d stay a team.

When the Marines went back to their places on the line, they walked in groups of two or three. They would stand watch together, eat together and joke together. But I was alone. I sat in the cab of the Humvee and watched them go. The events of the day overcame me all at once and I struggled to breathe without crying.

As darkness fell over Qalat Sukkar I sat alone in the dim green light of the radios. I felt sick for the shepherd boys and for all the innocent people who surely lived in Nasiriyah, Ar Rifa and the other towns this war would consume. I hurt for my Marines, good-hearted American guys who’d bear these burdens for the rest of their lives. And I mourned for myself. Not in self-pity, but for the kid who’d come to Iraq. He was gone. I did all this in the dark, away from the platoon, because combat command is the loneliest job in the world.

Nathaniel Fick, a classics and government major as an undergraduate, served as a Marine infantry officer in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq between 2001 and 2003. He was also a civilian instructor at the Afghan Counterinsurgency Academy in Kabul in 2007 and a member of the presidential transition team at the Department of Veterans Affairs in 2008. Since 2009 he has been CEO of the Center for a New American Security in Washington, D.C., where he lives with his wife and two young daughters. In April he was elected to Dartmouth’s board of trustees. This story is from his book, One Bullet Away, copyright © 2005 by Nathaniel Fick. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Co. All rights reserved.