The Eye of an Icon

It began, as many mysteries do, with a cryptic box—tucked away in a basement. But what a denouement: dozens of never-before-seen photos taken by the famed painter Georgia O’Keeffe. Cracking the case was Lisa Volpe, associate curator of photography at Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts, whose sleuthing culminated in a new exhibit now on tour.

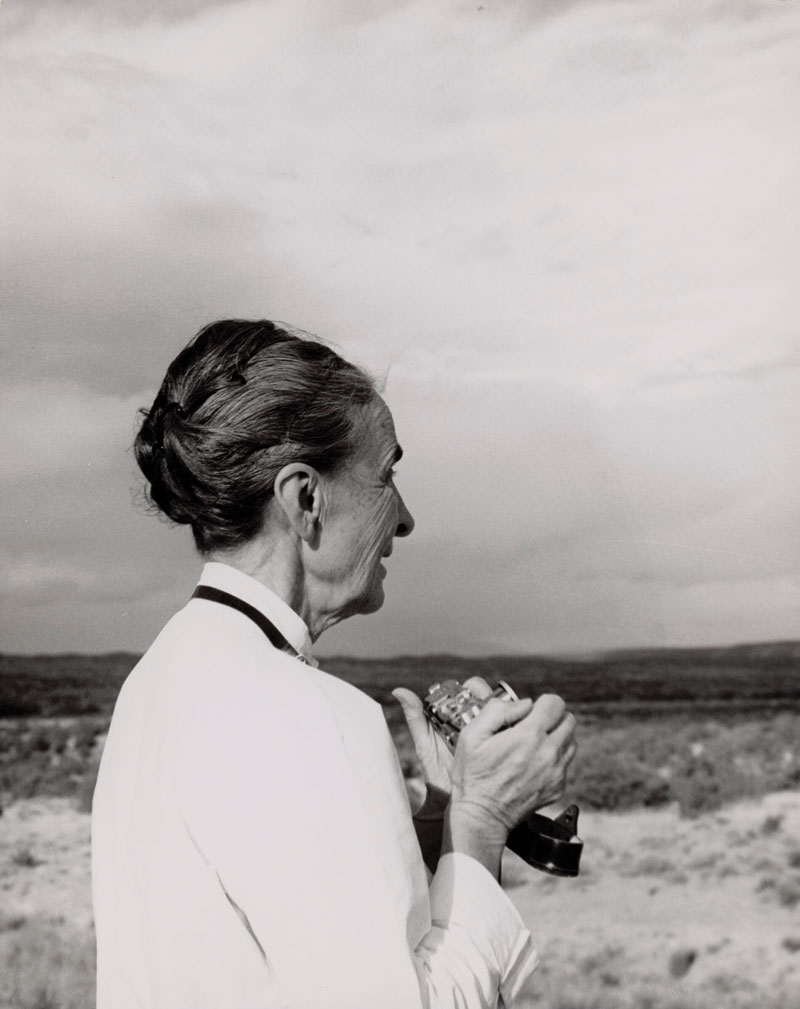

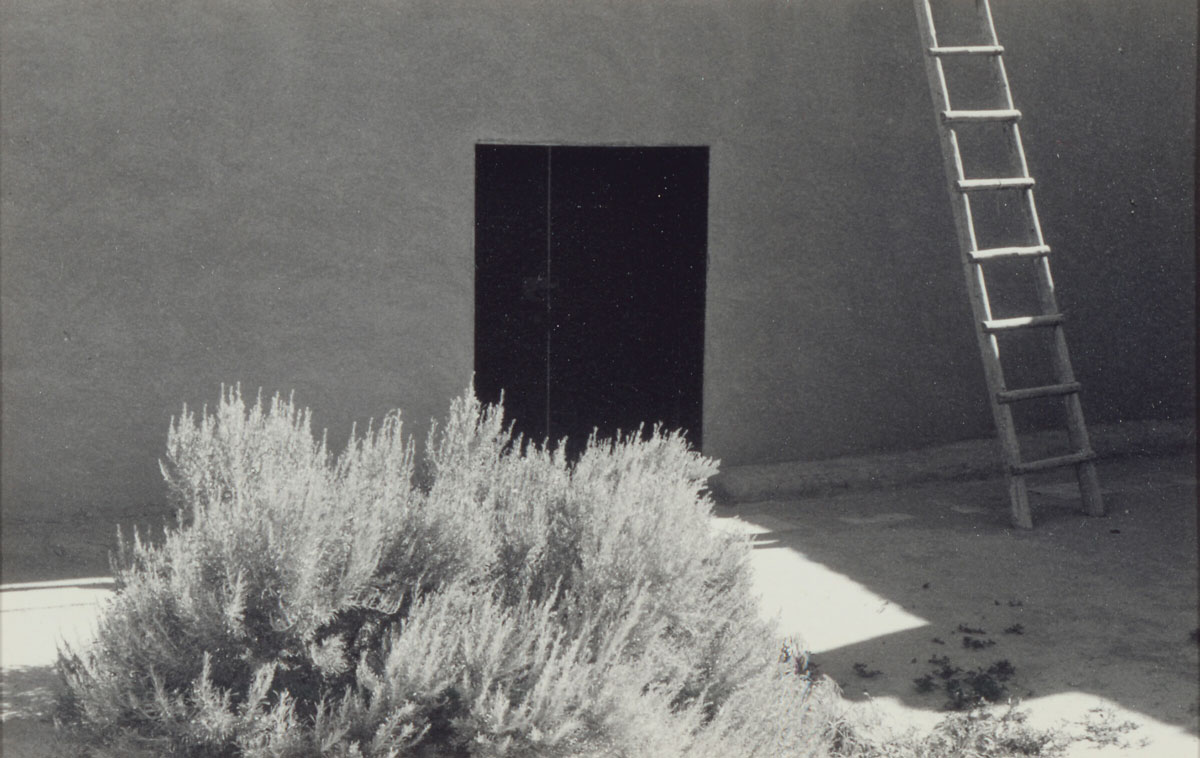

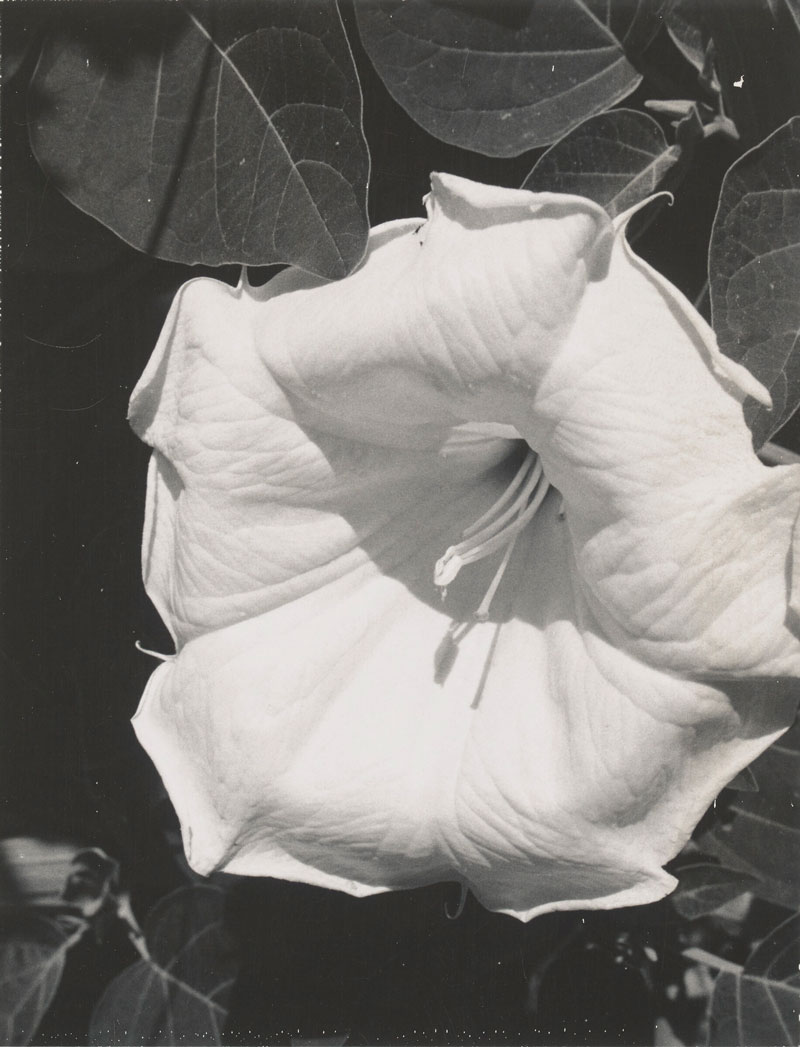

In her three-year, cross-country odyssey that went well beyond poring over negatives, Volpe mapped river canyons, consulted with a botanist and an eye doctor, studied Chow Chows, and analyzed mud bricks to unequivocally attribute 409 untitled black-and-white pictures—95 in the show and the more than 300 others in the companion catalog—to O’Keeffe. The artist aimed her Leica and Polaroid at many of the same subjects that dominate her paintings, including desert landscapes, flowers, animal skulls, and also the Chrysler Building. Volpe scrutinized them all.

“Lisa is thorough and organized and thoughtful and just a great, great researcher,” says Betsy Evans Hunt, a photo archivist familiar with O’Keeffe’s camerawork who helped Volpe.

The forgotten box that sparked Volpe’s quest contained about 200 photos. She learned of it in 2016 from Cody Hartley, director of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in New Mexico, where it had been gathering dust in a vault. Hartley knew some of the socked-away pictures were “by, not of” O’Keeffe, but he didn’t know how they came to be or if others existed.

“Initially, I was very scared of the cult of O’Keeffe, worried about the reaction from scholars and fans.”

Shortly after starting her job later that year in Houston, Volpe decided to get to the bottom of the O’Keeffe photos, none of which had ever been shown. They offered “really intriguing research potential because there is so much written about O’Keeffe, none of it about her photographs,” she says. “Curators don’t often get to say something so radically new about such an iconic artist. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, plus I love research.” With her first trip to the vault in Santa Fe in 2017, her journey began.

“Initially, I was very scared of the cult of O’Keeffe, worried about the reaction from scholars and fans,” Volpe adds. “I was very aware that I was taking on this mythic figure, and I had to do it right: ‘How can I do it? Should I do it? And especially, would it do her justice?’ ”

Volpe faced two challenges. First, she had to rule out other photographers, including O’Keeffe’s husband, the acclaimed Alfred Stieglitz, who died in 1946. But art historians say O’Keeffe had little interest in taking pictures during her marriage. Another possible suspect was Todd Webb, a stockbroker-turned-photographer trained by Ansel Adams who became O’Keeffe’s confidant in her later years. In 1955, Webb walked, motor-boated, and biked from New York to Santa Fe for a two-week visit before finishing his trip to San Francisco on a Vespa. “Funny, but she knows nothing of the operation of a camera,” Webb wrote in his journal in 1956. “She sees well, of course, and seems to have a sense of the photographic eye.”

While O’Keeffe favored straight-ahead framing, Webb took pictures from off-center angles. He also snapped single shots, while she preferred three at a time, according to Hunt, executive director of the Todd Webb Archive in Portland, Maine. For several days in winter 2019 she and Volpe huddled there over a long table, sorting out the two artists’ photos and comparing their styles. One complication: O’Keeffe and Webb often shared cameras when they took pictures.

Volpe also sought to precisely date all the images, including some with vague origins that she dug up at places such as Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. As part of her painstaking process, Volpe enlisted help from preservation officials to ascertain when O’Keeffe took some pictures of her New Mexico home. If photos showed walls made of cement, they were likely taken after 1959, when O’Keeffe first used cement to repair her mud-brick adobe.

Photos of O’Keeffe’s puffy, dark-coated Chow Chows were much tougher to ID, because through the years she had multiple dogs named Bo, Inca, and Chia. O’Keeffe’s letters helped clear up which Bo arrived when. Volpe also asked a Texas dog-show judge to explain Chow Chow facial characteristics and fur patterns to help her properly identify the dogs.

Red rock formations in Glen Canyon along the Colorado River in Utah and Arizona appeared in several photos, some of which O’Keeffe used as studies for later paintings. Volpe, who knew O’Keeffe made three trips to the canyon—in 1961, 1964, and 1965—sent dozens of images to Ryann Savino, who leads rafting trips in the area, for her water’s-eye-view take. “Lisa really took the time to make sure no stone was left unturned,” Savino says.

Volpe, who grew up in Youngstown, Ohio, majored in art history and calls Dartmouth’s darkrooms, then located in the basement of the Hop, “the most magical places on Earth.” Her interest in photography led to her interest in curation. “I loved the photos, but I didn’t so much love the taking of the photos,” she says. “This is what I was meant to do.”

More technical parts of Volpe’s research involved pinpointing the age of pictures by examining the types of gelatin silver paper on which they were developed. If the thickness, texture, and gloss of the pictures matched samples of Kodak Azo paper, for example, Volpe could date the photos to the 1950s. “With O’Keeffe, people really want to know her intentions, her practical means. Was she making art? Was she making documents?” says Paul Messier, chairman of the Yale Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage, which lent Volpe vintage paper samples from its collection of thousands.

A reporter Volpe spoke with several years ago inspired her tenacious approach. “The biggest thing I learned is never to hesitate to ask an expert for help. They’ll be flattered, not annoyed, to lend their knowledge,” she says. “This was the pinnacle of that.”

Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer travels to Massachusetts, Denver, and Cincinnati during the next year.

C.J. Hughes is a frequent contributor to DAM.