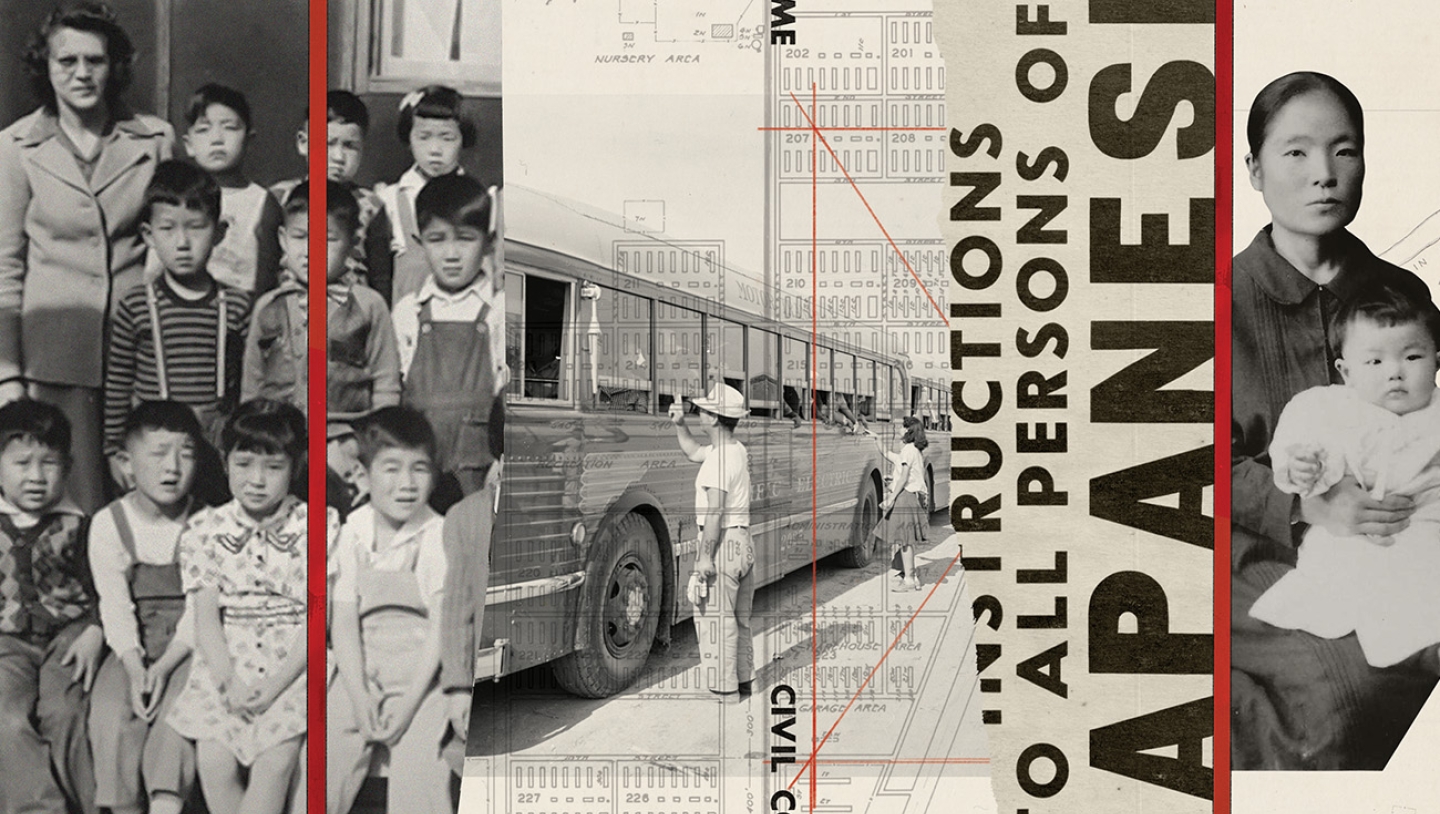

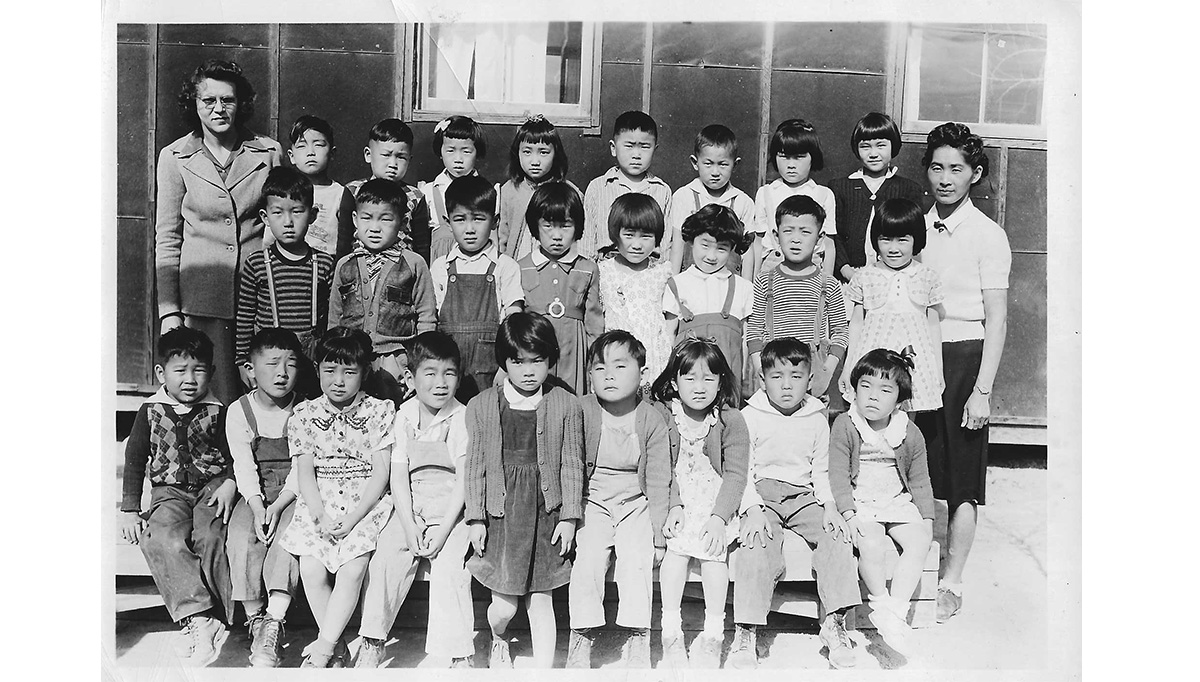

A school photo of a first-grade class, 25 children and two adults. In stunning contrast to what might be expected, not one tiny face cracks a smile. All look anxious, grim, drawn.

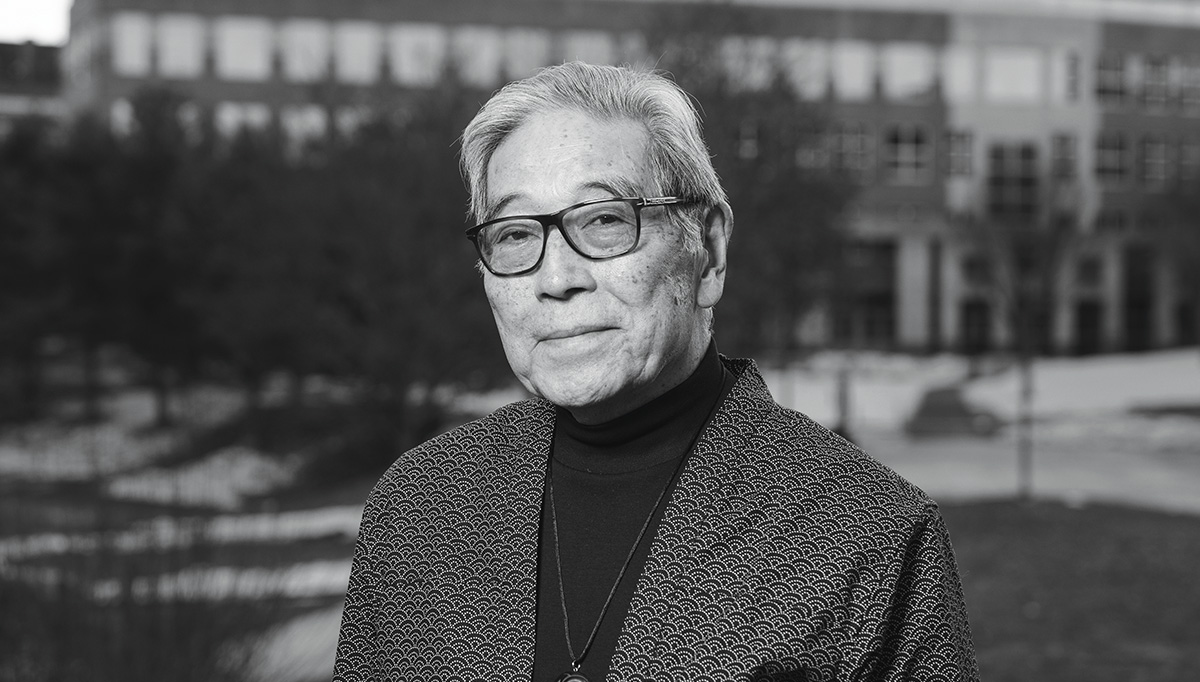

The photo—probably taken in early 1945—captures a class at the Poston Internment Camp, an Arizona facility where Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II. The boy in the top row at the far left, standing next to a teacher, is Joe Okimoto, who later graduated from Dartmouth and its medical school. He went on to a distinguished career as a psychiatrist who treated patients suffering from trauma, often incurred in childhood.

“I think that photograph says everything about the impact of chronic trauma that drains the spirit of young people,” Okimoto says. “It’s quite remarkable, the entire class—we all look so dispirited.”

Okimoto’s life experience and career have taken on a pressing immediacy now that the Trump administration plans to arrest and deport millions of undocumented immigrants and their families. Even Tom Homan, the president’s new “border czar,” acknowledges that a roundup of that magnitude will require detention camps to hold those arrested while the uncertain deportation process plays out. “We’re going to need to construct family facilities,” Homan recently told The Washington Post. “How many beds we’re going to need will depend on what the data says.”

The government crackdowns aren’t parallel. The overwhelming majority of the 120,000 incarcerated Japanese Americans were in the United States legally. Many were American citizens and had been living here for years. The concentration camps remain a terrible blot on American history and on the country’s record on civil rights. Today, it remains unclear how the Trump deportation plans will play out. Still, Okimoto knows firsthand the devastating and lasting impact that wholesale mass imprisonment can have on people.

“The trauma is inhumane,” he says.

During Trump’s first administration, the American Academy of Pediatricians spoke out forcefully against the detention of children and reaffirmed its position in 2022. The organization’s policy statement said in part, “Expert consensus has concluded that even brief detention can cause psychological trauma and induce long-term mental health risks for children.”

Charles Wheelan ’88, a professor of public policy at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business, points out that the affected children presumably had nothing to do with the decision to come to this country in the first place. “I think it’s safe to say that incarcerating children in any way at a young age is really bad for their brains, which is really bad for their future life outcomes, which is really bad for whatever society they end up in.”

For years, Okimoto spoke little about the incarceration he and other Japanese Americans had suffered. He was busy chasing success. “I was in survival mode,” he says. “The important thing was to figure out what needed to be done in order to be successful.” That changed as the political mood of the country changed. “I feel it’s my obligation to tell my story as often as I can, especially in this political climate,” he told a gathering at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine in February 2024. “It’s scary because there are threats that immigrants will be rounded up and put in concentration camps.”

From his home on Vashon Island, which sits in Puget Sound offshore from Seattle, Okimoto has taken a leadership role with Tsuru for Solidarity, an activist group made up of Japanese-American survivors of the incarceration and their descendants. The organization, founded in 2019, works through education and protest to end racist immigration policies and the use of detention camps. “The thing is that people didn’t speak up for me, so I feel I have to speak up.”

Okimoto, now 86, was 3 when his family’s incarceration began. He has almost no recollection of the three-and-a-half years they spent in the camps—a symptom, he explains, of trauma, which impedes the part of the brain that holds memory. His older sister, Ruth, recalls soldiers with rifles coming to take the family away. “I remember as a child, a 6-year-old, seeing these soldiers with the bayonets, and I thought, oh my God, are they going to kill us?” she told an interviewer years later.

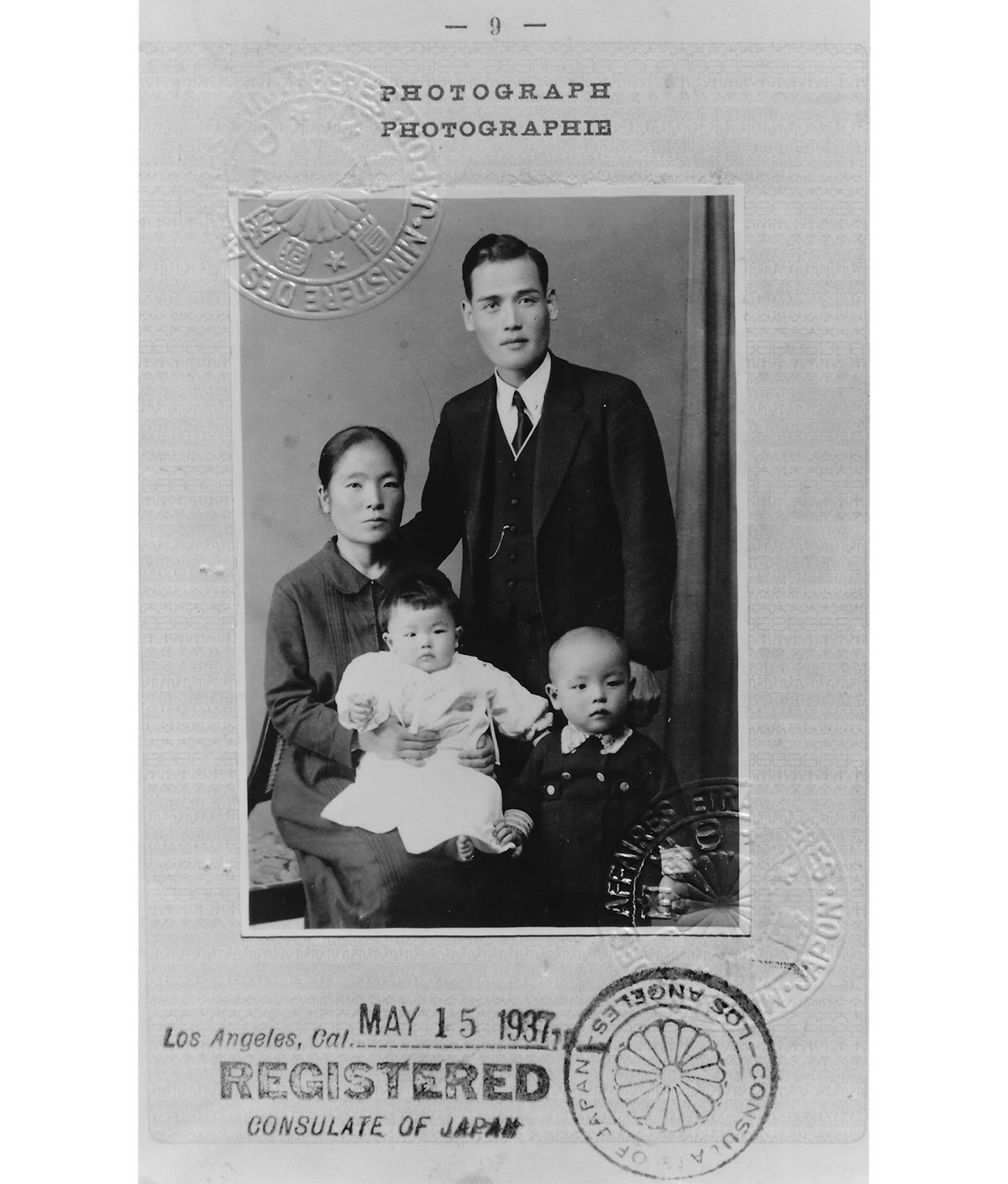

The Okimotos were relative newcomers to the United States. In Japan, Okimoto’s mother and father had each been comforted through personal crises by Christian missionaries. Both had subsequently converted and trained as Christian ministers. In 1937, Okimoto’s father was assigned to lead a congregation of Japanese Americans in San Diego. The U.S. Immigration Act of 1924 severely restricted Japanese immigration, but—probably because of their religion—the Okimotos were allowed to enter with their two children. Joe was born in San Diego in 1938.

The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, ignited a wave of anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. Politicians and military authorities inveighed against the supposed threats of sabotage and spying. Vicious anti-Japanese propaganda appeared, including ugly caricatures of Japanese faces. (Dartmouth’s Ted Geisel—Dr. Seuss, class of 1925—whose family’s donations to the College led to his name on the medical school, contributed cruel anti-Japanese cartoons to the American propaganda effort. Those drawings stain a career of work generally devoted to promoting generosity and inclusion.)

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, giving military authorities the power to round up Japanese Americans on the West Coast. The order didn’t single out any ethnic group, but it was applied strictly against people of Japanese descent. Arrests began soon after, forcing many families to sell their property at huge discounts. “Japanese immigrants were very successful in agriculture and fishing,” Okimoto says. Their competitors were eager to see them out of the way.

“The trauma is inhumane.”

The roundup was swift and thorough. A typical detention order “commanded Japanese Americans to bring bedding, linens, toilet articles, clothing, knives, forks, spoons, plates, bowls and cups sufficient for each member of the family,” write Richard Cahan and Michael Williams in Un-American, their 2016 book on the incarceration. Soldiers came for the Okimotos in May. Okimoto’s older brother and sister recall the sympathy and sadness of their non-Japanese-American neighbors. The family was first taken to a detention camp set up at Santa Anita racetrack near Los Angeles. Many of the imprisoned Japanese were housed in horse stables, which had been crudely converted to housing but still smelled of manure. Okimoto’s mother was in advanced pregnancy when they arrived. She cared for her newborn fourth child in a horse stall.

After a few months, the authorities shipped the family to a shabbily constructed prison camp on a Native American reservation in the Arizona desert. The camp, Poston, was the largest of 10 built around the West and at one point held a population of more than 17,000. Prisoners were housed in 100-foot-by-20-foot barracks, subdivided into up to six apartments, not separated by walls. Blankets strung from the ceiling offered minimal privacy. There was no running water. Communal bathroom and bathing facilities accommodated as many as 300 people. Temperatures ranged from blasting summer heat to raw winter cold. Windblown sand leached through cracks.

A few Americans, including the president’s wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, recognized the unfairness and cruelty of the incarceration, and even FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover said his agency had found no evidence of Japanese-American spies or sabotage. The government went out of its way to pretend the concentration camps were benign. Officials used Orwellian euphemisms—“Assembly Center,” “temporary shelter”—and sent in Dorothea Lange, a famed photographer, to take pictures. Of course, she wasn’t allowed to photograph watchtowers, barbed wire, or soldiers with guns.

Several Japanese Americans challenged the government action, and their case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which, in one of the court’s most notoriously bad decisions, upheld the incarceration.

The Okimotos remained prisoners until their release in September 1945. They returned to San Diego, where Joe’s father resumed his ministerial work. “Since my parents were ministers, they really didn't own anything to lose,” he says. “We lived in the parsonage.”

Joe doesn’t recall his parents ever talking about the incarceration. Ruth, however, says that as her father aged he suffered terrible nightmares, waking up screaming about no one coming to help. “Looking back, I think my father suffered from PTSD,” Joe says.

Okimoto grew into a quick and nimble halfback and linebacker, though he was only about 5-foot-7 and 150 pounds. He was co-captain of a high school football team that featured a star quarterback. Dartmouth’s coach, Bob Blackman, came out to recruit the quarterback and invited Okimoto along for the meeting. Blackman encouraged both young men to apply to Dartmouth. For a season Okimoto sat on the freshman football team bench. (The quarterback hated the snow and left after a semester.)

He joined the Glee Club but quit as a sophomore when he learned that on the spring concert tour the singers were going to stay with alumni families. “I was so intimidated, I refused to go,” he says. Okimoto recalls only one other Japanese American in his class, a young man he hardly came to know. He was intimidated by the academic rigor and the socioeconomic divide—he was a scholarship student, and many classmates came from money and private schools. He adjusted to winter, however—in fact, he became an enthusiastic skier—and did well enough in his studies to enter the medical school after three years. “I spent a lot of time in Baker Library,” he recalls.

Okimoto acknowledges that his five years in Hanover were difficult. “The overall experience was painful in a sense. It was so different culturally, social-class-wise,” he says. “I felt like an outsider. But, of course, the opportunity to have an elite education was something I really appreciated.” He completed the med school’s two-year program and enrolled in Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Sol Rockenmacher ’60, Okimoto’s medical school roommate at both Dartmouth and Harvard, recalls a friendly guy who was both bright and a strong athlete. The incarceration never came up. “He went on to help other people,” says Rockenmacher, “and it sort of helped him as well.”

Okimoto planned to become a surgeon, but while in a surgery program at the University of California San Francisco, the civil rights movement exploded around him. The events prompted him to reflect for the first time on his incarceration and the

racism behind it. Suddenly his surgery program seemed far removed from what was going on in the outside world. He earned a master’s in public health before turning to psychiatry, eventually qualifying as a psychoanalyst and teaching psychiatry at the University of Washington School of Medicine. He thinks he embraced psychiatry from a “dual motivation”—both professionally to gain the skills and training, “but also, I think, on a deeper level, I was wanting to heal my own trauma,” he says.

As a practicing psychiatrist, he worked through the years with troubled populations—addicts, people with eating disorders, soldiers suffering from PTSD, Asians with emotional problems. “I gravitated to patients who had been through trauma,” he recalls. “I think it was an unconscious thing.” In the 1980s and 1990s, medicine increasingly came to recognize the damaging effects of trauma. The research was hardly surprising to Okimoto. He points out that even Freud recognized that psychic conflicts often originate in childhood trauma. Okimoto applied the growing body of research to his practice, which often involved long sessions of therapeutic discussion, helping the patient to open up.

“Trauma has a way of leaving the individual with a heightened fear response,” he says. “The brain gets altered and becomes hypersensitive to threat. That’s a pretty major obstacle to get through in therapy.”

Meanwhile, the country haltingly came to recognize the appalling injustice imposed on Japanese Americans. In 1983, a commission appointed by Congress reported the incarceration resulted from “racial prejudice, war hysteria, and failure of political leadership.” In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill to “right a grave wrong,” as he put it, authorizing $20,000 reparations payments to 60,000 surviving men and women who had been imprisoned in the camps. “I split it and gave it to my two sons,” Okimoto says.

“I felt like an outsider. But, of course, the opportunity to have an elite education was something I really appreciated.”

In 1973, Okimoto married Jean Davies, a psychotherapist and children’s book author, and both brought two children from previous marriages to the union. Today their children and six grandchildren live nearby.

He retired as a doctor in 2016, and since then he has had more time to consider and research his family’s incarceration. In 2019, he and his sister returned to Poston as part of a pilgrimage made annually by Japanese Americans who were held there. The site features a memorial monument and a handful of decrepit old buildings, but almost all the camp structures have disappeared. “I was hoping some memories would come back,” he says, “but, unfortunately, they are pretty well locked away.”

The impact of buried experience can surface abruptly, however. Once during his talk at Geisel, recalling the anti-Japanese taunts from schoolmates immediately after the war, Okimoto briefly broke down. “Trauma has a way of coming up unexpectedly as a flood of emotion,” he warned.

Today, he worries that Trump is stoking the fear of immigrants in much the same way politicians demonized Japanese Americans in World War II. Where will it lead? Although he says that as a longtime psychiatrist he’s more comfortable listening than talking, he feels it’s important to share his experience and his concerns. The haunting photograph of 25 first-graders eloquently echoes his point.

Richard Babcock’s latest novel, A Small Disturbance on the Far Horizon, comes out in July.