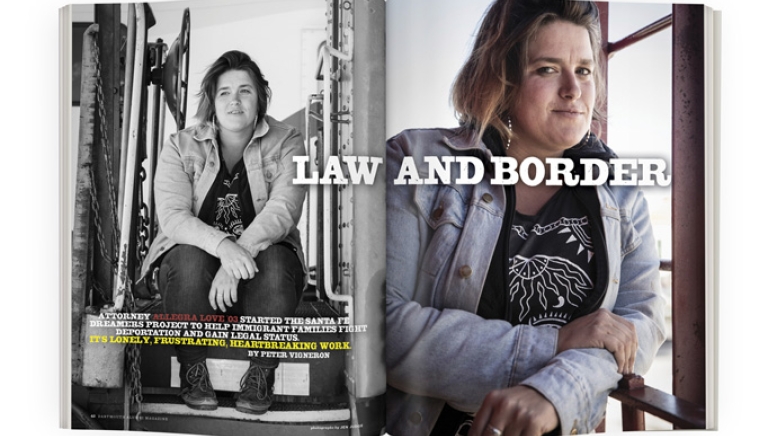

Allegra Love took a break from work in June 2014 and traveled from her home in Santa Fe, New Mexico, to Tenosique, a town in southern Mexico. Located 35 miles from Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala, the town is an important way station for Central Americans migrating to the United States. Love, an immigration attorney, was there to volunteer at a shelter for migrants. A rail line runs through town, and many migrants stay at the shelter as they wait for the train to pass through on its way north. The train is known colloquially as La Bestia, the beast. Riding it is exceptionally dangerous—two weeks before Love arrived, a toddler had lost a leg trying to catch La Bestia with his mother.

Love spent the evening speaking—in Spanish—with migrants whose questions were both practical and fantastic: What would happen when they crossed the border? How would they secure visas? Is it true that truck drivers and carpenters in the United States make $50 an hour? One woman told Love that she was migrating because her brother had been murdered. A group of young men from Honduras said they had been held for two days by a coyote, a trafficker, who had demanded more money before abandoning them near Tenosique. A young couple, carrying only a small backpack, was traveling with their 3-month-old baby.

Two nearby murals served as a backdrop for her discussions. One depicts the history of the shelter, a converted Franciscan church; the other shows areas of Mexico where cartels have made travel dangerous for migrants.

The next day Love worried she wasn’t doing enough. “You’re talking with people who desperately need some hope to cling to,” she says. She offered limited legal advice but knew those she counseled were unlikely to qualify for asylum. Getting into the United States, even illegally, was a long shot. Friar Tomas Gonzalez Castillo, who operates the shelter with a small group of friars, told Love that perhaps 10 percent of the migrants would succeed. The rest would be detained and deported by the U.S. government or possibly kidnapped or killed along the way in Mexico. (Castillo named the shelter La 72 in memory of a group of 72 migrants who are believed to have been murdered by the Zetas cartel in 2010.)

Love had become the bearer of very difficult news.

Sitting next to the cartel mural, Love allowed herself a few moments of worry. Charismatic and not easily discouraged, she has spent years working with migrants. But her clients are mostly safe—they have already arrived in the United States, unlike the people at the shelter. The migrants’ situation in Tenosique, on the other hand, is chilling. “I’ve seen the worst humanity has to offer. These are people fleeing violence, and their lives are in jeopardy,” she says. “Maybe it’s a hopeful thing that this is even happening in the first place, that people are even trying. Despite all the barriers—the threats of death, starving, not knowing what’s going to happen minute-to-minute—people are still doing this. In droves.”

In early 2007 Love was teaching second grade in the Santa Fe public school system when U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers conducted a series of raids in Santa Fe. During the Bush and early Obama administrations, raids such as these were common, and although they rarely targeted children, the kids in Love’s class scattered when the first raids happened. One day her class of 20 shrank to three students. Everyone else stayed home.

Love had moved to New Mexico in 2005 after teaching English for a year in the Marshall Islands as part of emeritus education professor Andrew Garrod’s Dartmouth volunteer teaching program. She grew up in New Jersey and moved to Wyoming in high school. After living in Hanover and the South Pacific, she missed the West. Her mother, who was then ill with terminal breast cancer and living in New Jersey, asked her not to leave the country again. New Mexico encourages bilingual instruction in its public schools, and Love faked knowing Spanish to get a job teaching second grade. “In the interview, I wouldn’t want to say that I lied, but they said, ‘Would you be interested in a bilingual position?’ and I was like, ‘Hell, yeah,’ ” she says.

By the time of the 2007 raid Love’s Spanish had improved, and she was a de facto link between her students’ families and Santa Fe’s Anglo community. Nearly all of Love’s students were from Mexico and, for their families, immigration status was a precondition of daily life: It dictated who could go to college, what kinds of jobs they could take, whether they could open bank accounts. During the raid Love could see how fearful these families were, but she had no idea what to advise them. “I had no skills, no understanding whatsoever” of immigration law, she says. She didn’t know the risks her students’ families faced or how they could protect themselves. Eventually Love’s students returned to class. That summer she volunteered for an organization called No More Deaths, which helps migrants crossing from Mexico through the Sonoran Desert in Arizona.

When she returned to New Mexico in the fall, she applied to law school at the University of New Mexico. When she graduated in 2011 she found that her legal education did not necessarily prepare her for a career in service. “Law school is a disorienting experience,” she says. “The idea is that you have to become an associate at a firm to get any skills.” Love knew she wanted to represent undocumented immigrants, but she didn’t want to work for a big firm and wasn’t sure she could go into practice on her own. She briefly considered working for the district attorney’s office, then decided to go back to teaching.

A year later the Obama administration announced an executive action known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which allowed a million immigrants who had been brought to the country as kids to apply for work authorization. As hundreds of children in Santa Fe became eligible to apply, Love realized how she could use her law degree.

From 2012 until early 2015, Love worked for an organization called Adelante within the Santa Fe school system. Adelante aids children who are homeless or on the verge of becoming homeless. Santa Fe has a large immigrant population and many of the families whose children are served by Adelante are undocumented. In the United States recent immigrants, though poor, tend to do well on many important socioeconomic benchmarks: They have high labor participation rates, according to the Migration Policy Institute, and several national studies have found they are much less likely than the rest of society to commit crimes or abuse alcohol or drugs. Love and Adelante’s executive director, Gaile Herling, realized that helping children secure legal status would be a powerful way to help settle their living situations, and Herling offered Love a staff job to represent families in DACA proceedings.

“I can’t think of any argument that makes it right, or even remotely justifiable, to have babies in jail,” says Love.

With Love as the in-house attorney, Santa Fe became one of the only school districts in the country to offer legal aid to undocumented families. Around 60 percent of public high school students in Santa Fe graduate and receive diplomas. Since 2012 the corresponding number for the children Love has represented is 96 percent. Additionally, documentation can have economic benefits: The American Immigration Council reported in the fall on a study that found that DACA-authorized immigrants have seen post-authorization income growth of around 45 percent. Having hundreds of families join the formal economy in Santa Fe, Love says, has been “absolutely transformative.”

Last winter the district tried to limit the scope of Love’s work as an attorney at Adelante, and she quit. In March 2015 she created a nonprofit called the Santa Fe Dreamers Project. Funding is limited. A Santa Fe youth services organization has loaned her office space and helps with accounting. Several people, including two attorneys, sometimes volunteer. A small grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development pays for part of Love’s salary, and she fundraises for the balance. Love has always lived modestly—she drives a late-1980s Subaru, uses a flip phone without irony and has never made more than $25,000 a year as a lawyer—but Adelante had provided benefits and paid vacation time. Eventually she hopes to hire other immigration attorneys as well as someone to do administrative work full-time. This would take an annual budget of around $150,000. Until then, the Dreamers Project is a one-woman operation.

During the trip to Tenosique in the summer of 2014, Love spent two weeks at the shelter and several days in the jungle on the Guatemalan border, meeting migrants as they crossed into Mexico. When she returned to Santa Fe in mid-July she learned that ICE had opened a jail in Artesia, New Mexico, and was detaining women and children there.

It was a symbol of the radical shift in immigration politics in the United States in the past few months. A year earlier Congress had seemed poised to pass comprehensive immigration reform, and public attitudes toward immigrants were relatively positive. During the next several months, however, gang violence in Honduras and El Salvador escalated and large numbers of migrants began arriving at the U.S. border. In parts of the country, anti-immigrant sentiment swelled. Many of the new migrants were women traveling with children, and in 2014 U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers processed more than 68,000 families, more than twice as many as the year before. Controversially, the Obama administration decided to open facilities to detain several hundred of these women and children in Artesia; the government had closed a similar facility in 2009 amid outcry from civil liberties groups. Suddenly, hundreds of migrants little different from those Love had met in Tenosique were being held in a detention camp four hours from her home in Santa Fe.

Under international law the United States must admit refugees when they present themselves at the border. But the United States has largely refused to grant refugee status to migrants from Central America because of laws that define refugees as people fleeing political violence or persecution. The unrest in Mexico and Central America, which is drug and gang related, does not qualify.

Until 2014 Love’s work as an immigration attorney had focused on affirmative immigration cases—situations in which undocumented immigrants approach the government and apply to stay in the country. After she returned from Mexico, attorneys from the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) recruited her to join a group of volunteer lawyers representing women in Artesia. (Immigrants, unlike U.S. citizens, are not entitled to counsel while in government custody.) The work was rushed and informal. The lawyers often put in 16- or 18-hour days, shuttling between the detention facility and a church AILA had rented in town. “It was literally, ‘You show up in Artesia, there’s this church, knock on the window and they’ll let you in.’ That was the protocol,” she says.

What Love and the other lawyers discovered in Artesia was harrowing: Nearly all of the women with whom Love consulted said they had left Central America because they were in danger. Many had survived horrific abuse at home and then again while traveling through Mexico. “People don’t make that journey, they don’t give their kids over to smugglers to cross a continent, unless they have a pretty good reason,” she says. At the detention facility women reported that guards had harassed them and their children, and in one case threatened to kick a child for playing with crayons. Many children, unaccustomed to American food, refused to eat. Others appeared seriously ill.

In Artesia, Love and the other lawyers attended bail hearings via videoconference, sitting in mobile trailers to argue cases with judges and government lawyers in immigration courts in Texas and Colorado. U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson has said that detaining women and children would act as a deterrent for other migrants thinking about coming to the United States, but the deterrence of future migrants cannot be used, legally, to justify detaining migrants already in the country. In court the government relied on a Bush-era precedent regarding a migrant suspected of terrorism, lending the hearings a sense of absurdity. No one on either side believed the women or their children were terrorists. Within the past year a federal court in California has twice rejected the government’s reasoning and ordered the administration to stop detaining families, though those decisions have been stayed while ICE lawyers appeal.

Love found the existence of the Artesia center both infuriating and puzzling. Syria’s refugee crisis has attracted enormous attention in the past year, whereas Central American migrants, who are also fleeing violence and mayhem, made the news for only a few months in the summer of 2014. “Why don’t Americans, on the whole, give a s--- about any of this?” she asks. Public inattention has allowed ICE to pursue policies she believes are gratuitous and unethical. “It just makes your head spin,” she says. The women aren’t criminals or flight risks once they’ve been connected to attorneys. “I can’t think of any argument that makes it right, or even remotely justifiable, to have babies in jail. I don’t have strong feelings about regular immigration detention. I don’t like it. But this is a whole different thing,” says Love.

Filing DACA applications in Santa Fe hadn’t prepared Love for refugee cases. Affirmative removal law is straightforward, but refugee law is both complicated and adversarial. Love found that the government attorneys and some of the judges were openly hostile. “That was really scary. I do not practice refugee law,” she says. Before 2014 Love had never even appeared in immigration court. “It’s the difference between helping someone with some traffic tickets and representing someone on felony charges,” she says.

Figuring out whether the women might qualify for asylum required that Love know exactly what they were fleeing. In practice, this has meant listening to hours of heart-rending stories of violence and loss, often told for the first time. In November 2014 the U.S. Department of Homeland Security closed the Artesia facility and transferred many of the women to a much larger jail in Dilley, Texas, owned and operated by the Corrections Corporation of America. Love has come to dread the 10-hour drive to Dilley, and regularly considers stopping her work with AILA. In Santa Fe her friends and family have urged her to step back, but nearly all of the women at Dilley are indebted to coyotes, and she worries that without the AILA project they wouldn’t find representation. Nationally, there are not enough volunteer immigration attorneys, and the shortage is especially severe in the Southwest. “I don’t know how to say no to refugees,” she says. “To say no to any case is hard, but especially a refugee case. Women who already owe their coyotes $10,000—I just don’t know where they’re going to come up with the money to pay a lawyer. The work that I’m doing is a fraction of the work that needs to be done.”

Last fall two of Love’s cases became especially demanding. DACA authorizations must be renewed every two years, and the government failed to process the renewal paperwork for one client, a woman who worked at a local bank. Love spent hours trying to reach government lawyers to fix the mistake, but the woman still lost her job. The second case involved a mother and three daughters who fled to the United States after the girls’ father was murdered in Mexico. “Mexican asylum cases are insanely difficult to win. Almost not worth trying, except you’ve got to try,” she says. As a stopgap, Love decided to argue that the mother’s probable deportation makes her an unfit parent, and to transfer the girls’ custody to a relative with legal status. “It’s hard for parents to stomach, having to say to a judge that they’re neglectful,” she says. But if the kids are awarded green cards, Love believes that the federal judge in the mother’s deportation case will let her remain in the United States, too. If the strategy fails (the case is still pending), Love is concerned the mother may be killed in Mexico. “It’s probably a loophole, but you have to try everything,” she says.

Adelante director Herling says that cases such as these have worn on Love in the past year. Last April, when Love returned from a tougher than normal trip to Dilley, she learned that a close friend, Rusty Cheney ’03, had died in a plane crash in Idaho. “That was a K.O. to my spirit,” Love says. “You know when you see boxers barely throwing punches, just putting their hands up? That’s how I was.”

“All of us at various times end up having to compromise,” Herling says. “It’s very hard for Allegra to do that. She sees that it’s a matter of life and death for some of these people. That’s difficult to deal with, but she keeps coming back. I think Allegra puts on a hard front, she appears like a hard-ass, and she really isn’t. She pays for it; her heart breaks sometimes. She wants to make it okay and she can’t.”

As Love has gained more experience in refugee law, she has become more comfortable taking cases that demand complex legal strategies. She now has around 20. “They take up a disproportionate amount of my anxiety and worry and sadness,” she says. “They’re so serious, and the consequences are so big.” She is also on pace to file 300 DACA cases this year, none of which she will charge for. (In New Mexico standard attorney fees for DACA applications range from $1,000 to $3,000.) Many of her clients find her through a walk-in clinic she hosts every Friday at a local church, and recently immigrants from across the region have started attending. “We were like, ‘Whoa, people will drive all the way up from Albuquerque for this service?’ And then we had a whole rash of people coming from Farmington. Wow—people are going to drive four hours? Then we had someone from El Paso, someone from Colorado Springs.” If she can raise enough money to hire staff, Love hopes to start traveling across the region, hosting clinics and then following up with clients over Skype.

In November 2014 President Obama announced an expansion of his 2012 DACA. It’s currently on hold in the wake of a federal injunction, but could eventually apply to some 5 million undocumented immigrants. Love thinks 8,000 people in Santa Fe could be eligible. “I was panicked,” she says of hearing about the plan just as she launched the Dreamers Project and prepared for a deluge of new clients. “The delay has given us time to put protocols in place, figure out best practices, but I don’t know what I’m going to do,” she says.

Most people think of service work in terms of what it will cost them: time with friends, money, prestige. Love is the opposite—she thinks in terms of the work she wouldn’t finish if the normal things in life became bigger priorities. Love is devoted to her twin sister, who moved to Santa Fe several years ago, and, after their mother died, she decided that she would never sacrifice time with her family. Everything else is fair game.

Her time in the Marshall Islands continues to inform her choices. “That altered everything for me,” she says. “It taught me about the love you have for people when you’re in service to them. Everything I’ve been doing, I’ve been trying to reconcile that feeling I had there—without having to live on a tiny island in the South Pacific.”

When Love began traveling to Dilley, she realized she needed a buffer against the misery she encountered there and started going to church. “That was to find guidance, I guess, not so much about Jesus,” she says, laughing. “A lot of church is fundamentally about how to be a better person, how to keep some of these contradictions from taking you down. But that’s life’s work, it’s not something I’m going to figure out in two weeks in a developing country. It’s something I might figure out before I die, if I’m really diligent about investigating it.”

Peter Vigneron is a former editor at Outside and a freelance journalist. He lives in Santa Fe.