Not every mentor you meet as a student works at the College. Sometimes you encounter townsfolk who turn out to be local Yodas, gurus who tip you to the Force, or the source, or whatever you want to call it. In the case of my off-campus Yoda, that was jazz piano and the perfectly cooked steak.

My Hanover was the late-1970s edition, with restaurants up and down South Main Street that are vanished now: The Village Green, Peter Christian’s, 5 Olde Nugget Alley. I worked as a waiter at pretty much all of them. Far at the end of town, just before the street takes a dive toward West Lebanon, sat an unprepossessing wood-frame building that had law offices upstairs and, downstairs, a steakhouse called The Bull’s Eye Tavern. It was run by an eccentric Armenian American named Richard Dohanian from Newton, Massachusetts. It was my favorite place to work and my favorite place to eat. The house is gone now, replaced by a galleria with a sushi restaurant, and I recently heard from a fellow alumnus—of the College and The Bull’s Eye—that Richard is gone too, dead last December in Kansas City, Missouri, at the age of 90.

The Bull’s Eye had a good run as college-town restaurants go: 16 years, from 1970 to 1986. It had 14 tables and an adjoining tavern room with a bar that propped up half the philosophy department, a third of the English department, and a motley crew of local artists, hippies, and reprobates. Richard was the cook as well as the owner: a short, solidly built guy with a big moustache and a million-dollar smile. He looked like Boris Badenov, the Russian spy from the old Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoons, a resemblance confirmed by his then-wife, who looked like Natasha. Richard’s kitchen made only four entrees: steak, pork chops, a bratwurst-and-sauerkraut plate, and a half-pound hamburger so resplendent that to call it anything but chopped beef was a slur. The burger was swaddled like the Christ child in a beer-and-cheddar sauce that was the Platonic ideal of the orange caulk they put on nachos at the ballpark.

Richard had rules, most of them involving steak. If diners ordered theirs well done, we were told to try and talk them out of it, citing the “insult done to the meat.” If that failed, we were instructed to get Richard, who would come out and engage the customer in an increasingly heated conversation that invariably ended with the customer leaving in a huff and Richard returning to the kitchen with a satisfied smile.

It was my favorite place to work and my favorite place to eat.

From Richard I learned about steak, obviously—how to cook it, cut it, eat it. I witnessed for the first time an actual joy of cooking and the contentment that can come from being in your own cook space, one built to your size and tastes. I learned about single-malt Scotch. I learned which professors at the bar I shouldn’t let follow me into the bathrooms when I was cleaning up at the end of the night. I learned the phrase “Sold American!” which Richard would bark whenever we’d bring in a new order, and which I found out only years later was a World War II-era ad tagline for Lucky Strike cigarettes.

And I learned about jazz, which Richard played in the restaurant, in the bar, and in the kitchen when he wasn’t listening to the Red Sox, and which he saw as his duty to instruct us in. Miles and Mingus and Monk, Coltrane and Dizzy, Getz and Dexter Gordon, the Modern Jazz Quartet. Cult figures such as Lennie Tristano and legends such as Charlie Parker. He loved pianists more than anything, and he loved Bill Evans the most. And the day Evans died in September of 1980, I came in for my shift to find Richard sobbing at a table in the back, cursing what the needle had done to a great artist—to so many great artists—and inconsolable in his grief. By then I understood, and I appreciated that he understood my grief when, less than three months later, the news came over the kitchen radio that John Lennon had been shot to death in New York City, and my childhood, which had had its start with the Beatles’ arrival in America in 1964, came to a sudden, irrevocable end.

In the spring of 1981, I left Hanover for the rest of my life. Richard shut The Bull’s Eye down in 1986 and moved away. The lessons stuck: how to slow-bake a potato until the skin crusts and the insides turn to silk; how to hear the soul in a bowed bass solo or a chorus of horns finding the pocket; how to look for the joy in everything, from cheese sauce to a closing-time conversation about a great book. I learned from any number of great teachers at Dartmouth. Richard Dohanian was one of them.

Sold American.

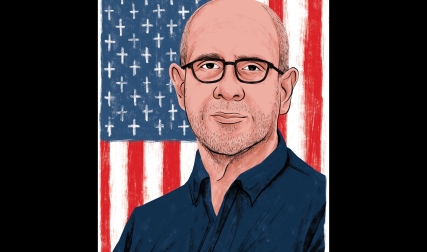

Ty Burr writes Ty Burr’s Watchlist, which can be found on Substack. He previously worked for two decades as The Boston Globe’s film critic.