Seven Days in May

John Kemeny did not enter the presidency to be a bull in a china shop. Early in his term, which began March 1, 1970, he was asked for his emergency instructions in case students occupied his offices. “Hand over to the students all unanswered mail and encourage them to burn it,” he replied, smiling. That unflustered disposition served him well when, just a few months later, he faced a potential campus crisis.

In late April the new president was off campus, visiting several alumni clubs. The country was erupting over the revelations that President Richard Nixon had secretly bombed Cambodia and Laos, illegally expanding the Vietnam War. On the road, Kemeny learned that students nationwide and at Dartmouth planned to soon vote on a student strike in protest. He alerted his staff to clear his calendar for Monday, May 4, so he could hold meetings about the situation.

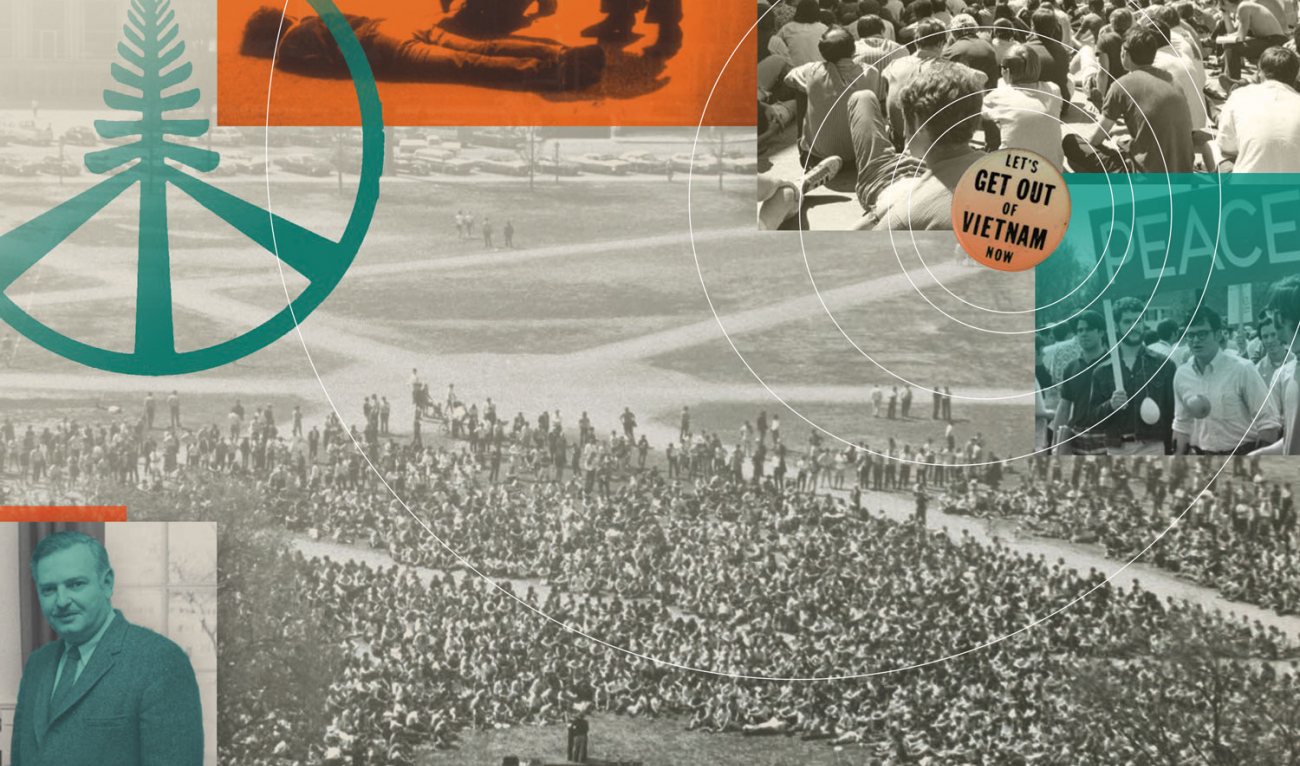

Kemeny spent that day in 12 hours of conversations with student leaders, faculty, and administrators. As they met, antiwar protests at Kent State University reached a tipping point when Ohio National Guard troops fired on several thousand student demonstrators, killing four and wounding nine. Kemeny learned of the massacre during his meetings. Tensions heightened.

His meetings generated “all kinds of advice, some of it very reasonable. But there was absolutely no consensus,” Kemeny later wrote. Around 8 p.m. he headed out for the student radio station—WDCR—to deliver his monthly address. Walking down the street, Kemeny knew he had to thread a needle. During the previous weekend he and his wife, Jean, had met with students to explore how Dartmouth might react to the Cambodian bombing. “In the course of the meeting, Kemeny switched from playing the devil’s advocate to exploring the possibilities of the kind of strike that was being proposed,” one student later recalled. “Mrs. Kemeny made a very strong argument to her husband that the community was facing a serious crisis and that there were times when even an institution such as Dartmouth had to break its traditional posture and respond.”

That advice, as well as the four dead kids in Ohio, surely occupied Kemeny’s mind as he considered what to say on the radio. When he got to the microphone, he delivered approximately 20 minutes of extemporaneous remarks and reaffirmed the notion that the president of Dartmouth should, and would, take a stand. “We are meeting tonight over the air at a time of one of the most troubled periods in American history,” he said. “I am greatly shocked by the death of four students, which is tragic in itself and a symptom of a national malady.” He announced the suspension of all regular academic activities for the remainder of the week and declared that the following day would be one of mourning. “I am urging all sections of the community to participate in intensive discussions as to how this community can best join hands in a united manner.”

The next day more than 2,500 people rallied on the Green. Bill Koenig ’70, president of his class and a quarterback on the 1969 Ivy champion football team, told students to treat the rest of the week seriously, not as a vacation. He called for a new kind of student strike, “not against Dartmouth, but by Dartmouth to provide a framework in which to act…to show our outrage at the war and repression at home.”

That evening, faculty voted to approve Kemeny’s call to cancel classes. The faculty also took up the question of what to do with students whose consciences might prevent their return once classes resumed. The faculty did not want to force any student to return, so professors came up with the “asterisk compromise.” Any student who wanted to drop classes that semester would get credit, but no grade, and an asterisk on the transcript would explain the circumstances.

In the ensuing days, students and faculty conducted an array of serious discussions and seminar-style inquiries, mostly on, but some off, campus. It was a unique educational opportunity that transcended the normal curriculum, yet was true to the purpose and mission of the College’s traditions. Professors offered seminars on topics such as the “anthropology of war” and the history of Cambodia. Students wrote hundreds of letters to Congress, and several undergrads published a nightly Strike Newsletter to notify the campus of the next day’s ad hoc events. Dartmouth essentially became a hotbed of international affairs intellectualism. Elsewhere, student strikes, some violent, closed more than 450 universities. Later in the month, two student protesters died at Jackson State University in Mississippi.

When chair of the trustees Lloyd Brace ’25 nervously called Kemeny to inquire if everything was okay in Hanover, the president glanced out his windows overlooking the Green. He told Brace that he saw hundreds of students “sitting in small groups in highly intense but peaceful discussions.” No riots. No violent protests. Nothing out of control.

The annual Green Key Weekend was scheduled for May 8-10. Some student leaders wondered if the gigantic bacchanalian affair should be canceled and sought Kemeny’s advice. He encouraged them to go forward with their plans. The students needed to let off some steam. “I told them that by the end of the week everyone would be exhausted, and that students needed and deserved a chance to relax,” Kemeny later wrote.

“We witnessed a pulling together of the Dartmouth community, in which I take pride,” said Kemeny.

The students asked him to speak to the crowd that Saturday evening, so he and Jean joined a couple thousand revelers in Leverone Field House with a band—The Youngbloods—and dancing. Students greeted the couple with massive applause. “As Jean and I walked in, two different students handed me lemons,” Kemeny later recalled. (Immediately after Kemeny canceled classes, William Loeb, publisher of the conservative Manchester Union Leader, had argued in an editorial that Dartmouth had “picked another lemon” in selecting Kemeny as president.) In his remarks Kemeny praised the students for their conduct in the wake of the shootings. “I couldn’t think of a good ending, so I tossed the two lemons out into the audience,” he later recalled.

On May 10, 100,000 antiwar protesters marched in Washington, D.C. The next day classes resumed at Dartmouth. Kemeny wrote an update to parents and alumni. He stressed that students had acquitted themselves well. They had engaged in constructive, educational, and peaceful activities, he wrote. The undergraduates and their actions “are proof that the College is continuing its traditional role of training leaders for the nation.”

The summer of 1970 came and went. In the fall, students returned to campus and calmly went about their business. “While many other campuses were deeply divided and scars were inflicted that would take years to heal,” Kemeny recalled several years later, “we witnessed a pulling together of the Dartmouth community, in which I take pride and which was most beneficial to the institution.”

The Vietnam War dragged on tragically for three years after the Kent State killings. When it ended, Kemeny released a statement: “I am relieved that the longest war in American history is over. We must now take stock and try to learn a lesson from this terrible conflict. I firmly believe that all nations must renounce war as a means for the settlement of international disputes.”

The 1960s and 1970s sank many college presidents. The passions and protests stirred by the expansion of Nixon’s war and the tragic events at Kent State and Jackson State were catalysts that shortened presidential tenures and horribly diminished the credibility of presidents on many college campuses. It was not by luck or a fluke of nature that Kemeny avoided those fates. From the outset of his career, Kemeny’s voice was consistent, constant, and undeterred, always crying out for progressive changes and for human values, along with asserting justice and social equity on the Hanover Plain.

Stephen J. Nelson is a professor at Bridgewater State University and the author of seven books about colleges and their presidents, including John G. Kemeny and Dartmouth College (2019). Nelson worked at the College from 1978 to 1991.