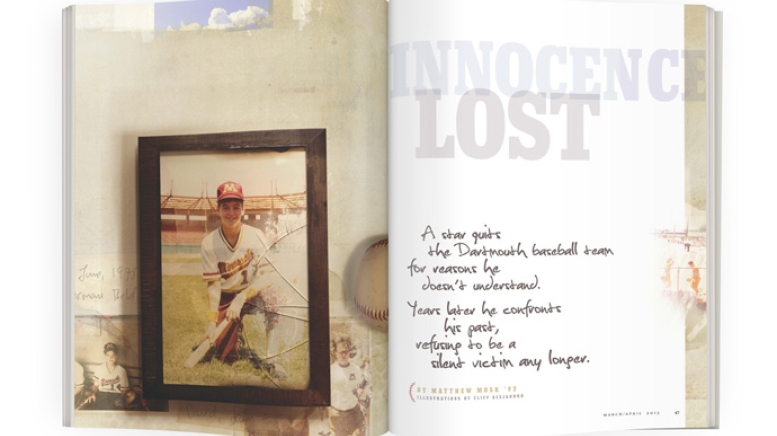

When David Wiser ’87 was recruited out of Minnesota as a top Dartmouth baseball prospect, coaches viewed him as a tantalizing talent: He was a power hitter with poise behind the plate. During his senior year in high school Wiser’s team had played for the Twin Cities championship at the Metrodome, the cavernous major league ballpark of the Minnesota Twins. In the third inning Wiser launched a grand slam off the left field wall, and in the fifth hit another wall-banger for a double, finishing 3-for-5 with seven RBIs in the proverbial game of his life.

Dartmouth coach Mike Walsh still remembers hearing about the game and wanting Wiser for a team he was trying to rebuild. When Wiser arrived in Hanover, it seemed he would deliver on that promise. Despite tough competition at catcher, Wiser made it into several varsity games as a freshman, and when starter Todd Twachtmann ’87 broke his thumb early in the 1985 season, Wiser took over as the team’s No. 1 catcher.

Beyond his skills on the field, Wiser was also emerging as a key figure in the locker room, Walsh recalls. Outgoing and humorous, the kid from Minneapolis had an amazing knack for imitating teammates and coaches. “He was very popular,” Walsh says. “And funny. He could mimic anyone. I only learned later on he did what some of the guys said was a spot-on impression of me.” But the happy-go-lucky kid who served as president of the fraternity that would become Chi Gamma Epsilon and whose partying earned him the nickname “Bud,” as in “Bud Wiser,” harbored demons that would, during his junior year, lead him to visit Walsh’s office to make a surprise announcement: He was quitting the team.

As Wiser remembers it, he told the coach he had realized he was not going to be drafted into the majors. It was time for him to focus on academics.

Walsh was stunned. Only years later, when Wiser revealed the ugly story of a childhood robbed of innocence and how he confronted that dark past in dramatic, public fashion, was Walsh able to make sense of the conversation the two had in his office decades earlier. “He was dealing with much bigger issues than anyone knew,” the former coach reflected recently.

Two days after graduating near the top of his class, Wiser drove his Volkswagen Rabbit to Cincinnati, Ohio, to take a job as a marketing assistant with Procter & Gamble, working on Scope mouthwash. Wiser excelled but was racked by the same worries he now says drove him from baseball. It was a pattern of not trusting authority figures: “I kept thinking, ‘They’re not supporting me, they don’t want me promoted, they’re setting me up.’ ”

Tom Blinn, a colleague at the time, said Wiser could not seem to accept criticism from senior managers and reacted in a way that didn’t seem to fit his otherwise charismatic personality. The flash point came when Wiser received a copy of the CEO’s new mission statement. “Dave came in to me and said, ‘I think a lot of this is off base. I’m going to go talk to him.’ And he did.” Afterwards, Blinn pulled Wiser aside and cautioned him—a conversation Wiser still remembers. “He said, ‘Chief, you’re one of the brightest marketers we have here, but some of this managing up stuff has got to change or it’s going to hold you back.’ ”

Wiser took the cue. “I remember him coming in after he had started seeing a therapist [in May 1990] and sharing it with me. I thought it was a great idea and encouraged it,” Blinn says. “He told me it was helping. Somewhere in that dialogue, he confided in me that he thought he had found the root cause. It caught me completely by surprise.”

The breakthrough came one morning in the fall of 1990 when Wiser stepped out of the shower and his girlfriend (now wife), Elizabeth, came up behind him and wrapped her arms around him as he looked into the steam-covered mirror. He says what he saw in the reflection looked like an old film clip. And the image staring back from the mirror was not that of Elizabeth. It was Gary Downing, his Little League baseball coach.

“Some file was accessed. Some switch got flipped,” Wiser says now. “It just freaked me out. Elizabeth said, ‘You look like you’ve seen a ghost.’

“I told her I had.”

As Wiser continued to work with his therapist into 1991, trying to come to grips with distressing images of his Little League coach that had been haunting him, a national debate was raging in psychology circles about recovered memories in cases of sexual abuse. Beginning in the early 1990s there had been a wave of court cases involving “recovery specialists,” therapists who encouraged people with certain symptoms to consider the possibility they had been sexually abused—even if they had no recollection of the abuse. The approach was rooted in the notion that victims had repressed the memories because they were too traumatic to process. Treatments including hypnosis were used to help victims recover these painful memories and, with luck and effort, put them to rest.

On the other side of the debate were parents who said they stood wrongly accused of being abusers. They argued that thousands of people who never suffered mistreatment had been misled by the suggestive efforts of their therapists. Groups such as the False Memory Syndrome Foundation of Philadelphia sprouted up to assist these parents and authority figures and led some victims to recant. The American Psychological Association eventually convened a task force to study the question, but what resulted was an ambiguous statement saying, in essence, there was no clear answer.

Wiser says his months of “extensive, painful psychotherapy” helped him recall real events buried in an inaccessible part of his memory for years. “I knew in high school, I knew in college and I knew after college that something was wrong,” he says. “I just didn’t know what it was.” Whatever it was had prematurely ended his college baseball career and now was poised to derail a professional career that had just started.

The abuse began on the road. At the age of 12, after a series of grueling interviews and tryouts, Wiser had been chosen as a member of the Minnesota Little Gophers, the state’s most elite group of 12- and 13-year-old baseball players. Only 20 were selected from the more than 450 who applied. The team competed in some of the top baseball tournaments in the world. They wore the same uniforms as the University of Minnesota men’s team and faced off against the best that Asia, Canada and Latin America had to offer.

The Little Gophers’ coach, Downing, worked as a campus police officer at the University of Minnesota. He showed an intense interest in his players, subjecting applicants to one-on-one interviews during which he asked the children detailed questions about their home lives and their relationships with their parents.

Little League trips could stretch for weeks, the Little Gophers crossing Canada or riding in a bus around southern California. At the World Games in Puerto Rico the Little Gophers played elite clubs from Venezuela, Colombia and Mexico. Wiser recalls one game against a team whose star was outfielder Roberto Clemente Jr.

On the road players slept four to a room, and Downing roomed with three players in a suite. Sleeping arrangements would put two players in a common area, while a third player would sleep behind a closed door—in the same bed as the coach.

“In 2012, if my son came back from a soccer tournament and said the coach asked to share a bed with him, I’d go and find my firearm,” says Wiser, a father of three teenagers, the youngest of whom, 13-year-old Sam, plays baseball. “Back then, no one asked those questions.”

Wiser says the player selected to sleep in the coach’s room received special treatment—chocolate, sodas and other treats that were off limits to others. In exchange, the coach expected back rubs and asked players to sleep in their underpants or, in some cases, in the nude. Wiser said that on at least one occasion, Downing rubbed him in his genital area.

Wiser says he roomed with Downing on two of three trips he made with the Little Gophers, including the California journey that stretched for three weeks. “You’re talking 20 nights,” Wiser says. “I wouldn’t have been able to articulate back then why I didn’t want to stay with him. But when I told him I wanted to hang out with my teammates in the main room, his reaction was meant to send a message: We had a double header that afternoon, and he didn’t play me.”

After completing therapy early in 1991 Wiser felt better, but was “horrified” to learn that Downing was still coaching. “I realized I had to stop him,” he says.

“I made calls to the Bureau of Criminal Prevention, the Minneapolis police. I told them what happened, we’ve got to shut this guy down,” Wiser says of efforts he made in the spring of 1991, shortly before his marriage to Elizabeth. “I’m sure I was just another phone call to them. I kept getting the same answer: ‘Hey listen, that was 14 years ago, that’s well past the statute of limitations. Even if it is true, we couldn’t prosecute him.’ ” Then Wiser reached out to Joel Grover, investigative reporter at ABC’s Minneapolis affiliate. Grover did not dismiss Wiser’s allegations, nor did he take them at face value. If Downing had abused Wiser, he said, there were likely others who had suffered the coach’s advances.

Into the winter of 1992, while working by day at Procter & Gamble, Wiser spent his evenings wearing the hat of an investigative reporter. He scoured phone books looking for old teammates and those who played for the Little Gophers in the years before and after he did. He gathered old team rosters, casting a wide net for potential victims. He called dozens of former players.

“I got all kinds of responses. Everything from a hushed ‘I know what you’re talking about, that happened to me,’ all the way to ‘I don’t know what kind of a freak you are, don’t ever call me again,’ ” he says. From each year’s team, Wiser learned, there were two, three and sometimes four players who remembered being selected to sleep in Downing’s rooms, remembered the coach’s odd requests, his interest in taking photos of boys in the nude. “It became really clear that this was a pattern,” Wiser says.

After several of the former players agreed to be interviewed by Grover on camera, the reporter told Wiser he had one more request before running the story. He wanted Wiser to try to confront his former coach. “These guys never admit what they do,” Wiser says. “Look at [Penn State assistant football coach] Jerry Sandusky. He still hasn’t acknowledged what he did. But Joel thought it was worth trying. He told me, ‘It’s a long shot, but let’s take it.’ ”

It had been 14 years since Downing coached Wiser on the Little Gophers, but it wasn’t long on the phone before the two men were engaged in a friendly chat. Wiser told Downing he was going to be in the Twin Cities to work on a Crest Toothpaste account and suggested the two connect for lunch. “You can tell me where the program is these days, how I could help,” Wiser coaxed.

A day before they were scheduled to meet, Wiser sat down with Grover, as well as the TV station’s lawyers and a law enforcement specialist who was trained in getting criminal suspects to talk. Wiser spent the day mapping out his approach. He was ready.

He met with Downing at a Hardee’s restaurant near the University of Minnesota campus. Wiser had taped a recorder onto his back and put a microphone under his jacket. Two TV producers went early and set up with cameras hidden in a briefcase and an athletic bag. Then Downing arrived.

“It happened pretty quick,” Wiser recalls. “I made it clear to him that I remembered exactly what he did, but I wasn’t coming there to yell at him or turn him in. I was there to understand why. His answers were almost comical. Everything that I talked about remembering him doing, he said, ‘Well, oh well, no, you’re right, that was in bad taste. That was poor taste. But it didn’t happen again.’ ” Wiser kept his emotions under control even though he later said he was shaking inside.

The most dramatic moment came as Wiser left the restaurant and started to get into his rental car. After spending lunch calmly telling Wiser his behavior was a thing of the past, Downing now took a more aggressive tone, stepping up behind Wiser and warning him not to share the contents of their discussion with others. On the secretly recorded video, Wiser looks angry.

“I’m a 27-year-old adult, in therapy because I was sexually abused by you when I was 12 years old. And you’ve got to understand that,” Wiser says, jabbing a finger at Downing’s chest. “Do you understand that?”

“Yes, okay, okay,” Downing says, arms crossed in front of him.

“That’s what this is about. It’s about nothing else,” Wiser says.

“But that was the year that everything with this program, honest and truthfully, changed,” Downing says calmly. “The situation, sleeping with you, sleeping with these other kids, whatever it was….Very poor taste.”

“If you’re telling the truth, I’m glad to hear that it’s stopped,” Wiser says.

“I am. I am,” Downing says, now standing no more than a few inches from Wiser’s face. “I’m looking you right straight in the eye and I’m telling you that.”

The broadcast of the recorded exchange, aired over two consecutive nights in November 1992 on the late news in Minneapolis, was explosive. By the time of the second broadcast Downing had been suspended from his campus police job. Before the following spring the Little Gophers baseball program was finished.

Wiser was elated. He compared his feelings in the moments after the confrontation with Downing to the greatest moment in his baseball career: the Twin Cities championships at the Metrodome. “If he had shot me dead in the parking lot I would have gone out knowing he was going to go down,” Wiser says now, noting that Downing had been armed with the firearm he wore on the job during the entire confrontation. “He was going to be exposed and we put him out of business.”

After the broadcast, speaking through an attorney to the news media, and speaking himself during the trial that resulted from a civil suit filed by Wiser, which required more than two years of trial preparation, Downing denied the allegations against him. He told a local paper he had been “set up” by the TV station. In 1996 a jury in Hennepin County decided that Downing was liable for sexual abuse (but found that the university was not responsible for his conduct). Downing’s attorney told local newspapers that his client was simply “glad it’s over.” Wiser was awarded $2.5 million in damages but never collected any money.

The demons that had been haunting Wiser through college and into his professional life had been vanquished. Wiser’s professional career flourished, as did his family life. He now runs a head-hunting firm with his wife and Tom Blinn, the Procter & Gamble colleague who had initially encouraged him to confront the issues that were holding him back.

Last year, after coverage of the Sandusky scandal placed the subject of sexual abuse by coaches in the headlines, Wiser’s lawyer began getting requests from the media, and Wiser began reflecting on his 1992 television appearance. “There was the benefit for other people and the benefit to me personally,” he says of having brought his story to the air almost 20 years ago. “First and foremost, I knew we were shutting the guy down. I knew it would feel really good knowing there would be no more victims. It was also very helpful to me therapeutically—it was all about rebuilding self-esteem and self-worth.”

But, despite the entreaties, Wiser was hesitant to go public again. “I talked with a number of television producers and I just wasn’t comfortable. The only time I talk about this is when I think it’s going to be helpful and beneficial,” he says. But when he began talking with an ESPN reporter about her interest in the story, Wiser began to reconsider. Maybe, he thought, his story could provide a pathway for others who had suffered as he had. “Elizabeth was sensitive to this,” Wiser said of his wife. “She was dialed in to the issue. She really wanted to use this as a light for people.”

Wiser sat his kids down to share what had happened to him. Predictably, they were outraged on his behalf. ESPN then produced an extensive report, and Wiser has been gratified that it indeed became a source of inspiration to those who had suffered abuse in silence and never been afforded the opportunity to face down their abusers as he had.

Wiser says one of the biggest lessons he took from the experience was the value of forgiveness. “As long as I let God know that I forgave the coach, that I believe we are all good people and due to other factors we take wrong turns, that would be enough,” he said.

The other lesson: Always be vigilant. Wiser’s middle daughter is 16 and plays soccer on a nationally ranked club. “Guess who was responsible for all the team’s travel planning?” Wiser laughs. “Nobody really knew why I was so happy to help. I don’t think people should apologize for being vigilant or dialed in or willing to step up and ask questions.”

Matthew Mosk, an investigative reporter for ABC News in Washington, D.C., is a frequent contributor to DAM. He lives in Annapolis, Maryland.

To read the report produced by ESPN, click here.