A Sense of Peace

As I began to pour a pitcher of bug juice at sit-down dinner, a junior grabbed it—and slammed it violently onto the table: “New boys are served last, rat!” he shouted. It was my first year at boarding school—long before Dartmouth. Often I took walks to clear my head. Before sunset, through a light breeze I’d walk down from the top of Seminary Hill in Alexandria, Virginia, which overlooked the Potomac River and the National Mall. Once at the bottom, not quite able to see up the hill, I’d cross a grassy swale through blocking trees to get a clearer view. There, I would turn around, lonely, sometimes teary—and gaze at her from afar: Ah, she was exquisiteness. She was the main building of Episcopal High School. Back then, the pain of not fitting in as a black student at an elite Southern school was overwhelming. Sadly, the mysterious, elegant grey mansion in the distance was my only true friend that year. Her splendor—the dramatic portico of columns at the finale of a serene tree-lined drive—made me fall in love with and solidified my interest in architecture. I always knew there was something special about her, but I couldn’t put my finger on it.

Turns out the “something special” was that Hoxton House, as it is known, was a long-lost national treasure. Later, as a Dartmouth student captivated by its architecture, I embarked on a quest to identify the early-American architect who designed her. Along the way I not only found a sense of belonging and connection, but also my voice as an architectural historian.

By 1998 I was an intern architect in New York City. I was intrigued by Classical houses. The next fall I attended my high school alumni gathering in a penthouse above Central Park. At the reception an alumni rep (who was also a Dartmouth alum interested in architectural history) told me that a recent historic preservation investigation had revealed Hoxton as the long-lost home of George Washington’s granddaughter, Eliza. The architect was unknown. That night on the terrace—staring into a dark moonlit sky—I started to wonder obsessively: Who designed Hoxton?

A few years went by. Based on my growing interest in the history of architecture, I enrolled at Dartmouth to pursue a course of study focused on, and coalesced around, architectural research. I began meeting with professor Angela Rosenthal in her book-filled office upstairs in Carpenter Hall. “You with the sad eyes—don’t be discouraged,” she would tell me. Rosenthal took me under her wing, and over time introduced the tools needed for scholarly research. She recognized my frustration in my search for Hoxton’s architect. “Just go for it. Don’t be afraid,” she told me in her lovely German accent.

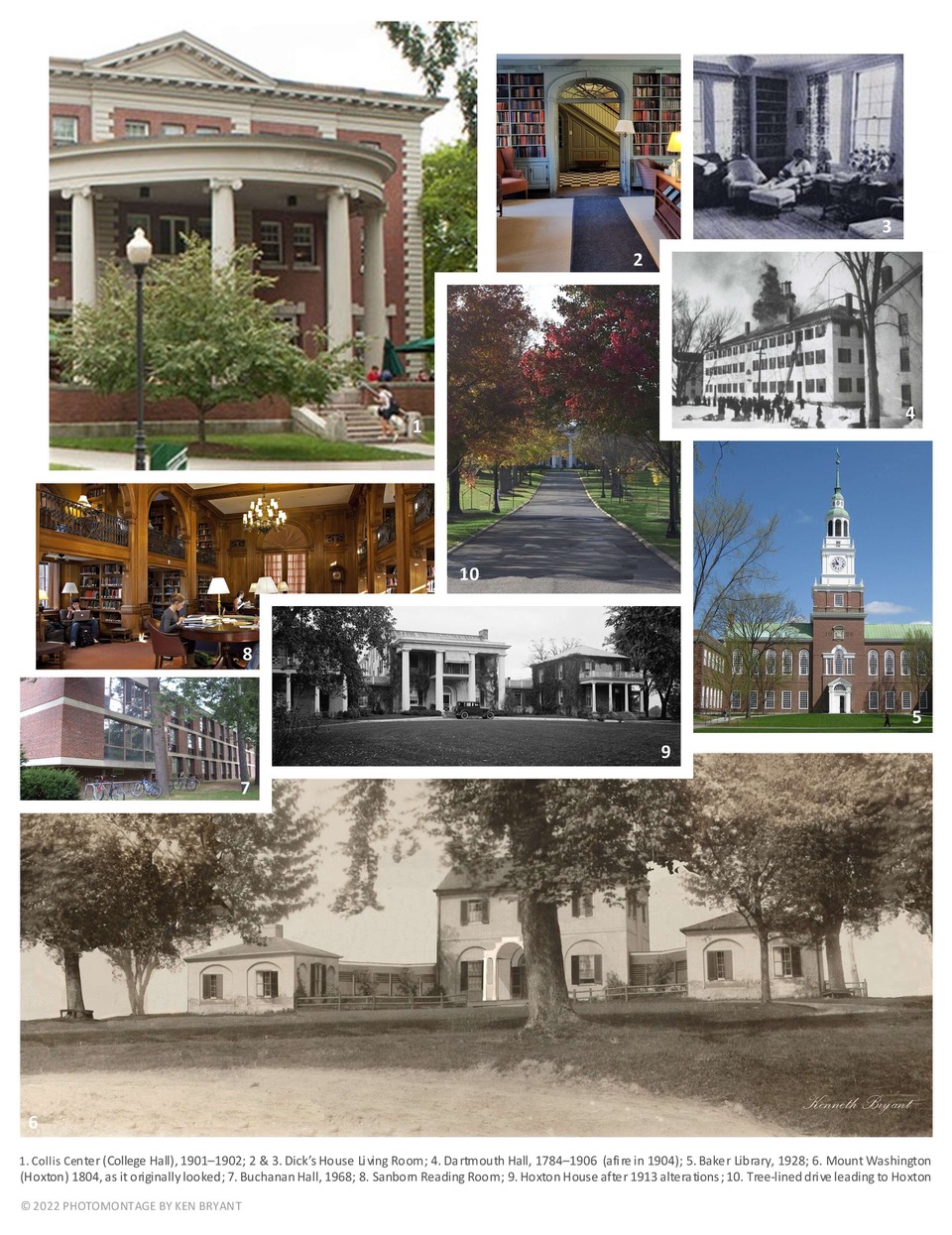

I still felt lost. In the Sherman Art Library, a librarian directed me to the Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals. She cleared her schedule and taught me to use the index. I impressed upon her the context and significance of my undertaking: “The discovery of Mount Washington—Hoxton—had solved the century-old puzzle of the missing link in a quartet of great American houses erected by four siblings dubbed the First Grandchildren of the United States,” I told her. The librarian’s jaw dropped. “The four include Woodlawn, Tudor Place, Arlington House and Mt. Washington.” Though situated miles apart, they form a group as harmonious as Dartmouth’s “Gold Coast” Cluster (1913–29), I noted. “Really?” she asked, mouth agape. “Yes, ma’am and I want to crack the riddle of who designed it,” I answered. She then recommended investigating the architects of similar houses.

Deep down I thought if I solved the mystery I’d finally be accepted by the good Old Boys of EHS—something I longed for.

I trudged through the snow to my dorm, Buchanan Hall (1968)—one of the few High Modern buildings on campus. I emailed my advisor Myrna Frommer, an oral historian, for advice. “You should conduct a series of research interviews to help narrow the list of suspects,” she replied, and that’s exactly what I did. Eminent architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson took my call, and Frommer’s suggestion proved fruitful. Before long I composed a final list of probable architects, which included Dr. William Thornton, Benjamin Latrobe, William Lovering, and George Hadfield.

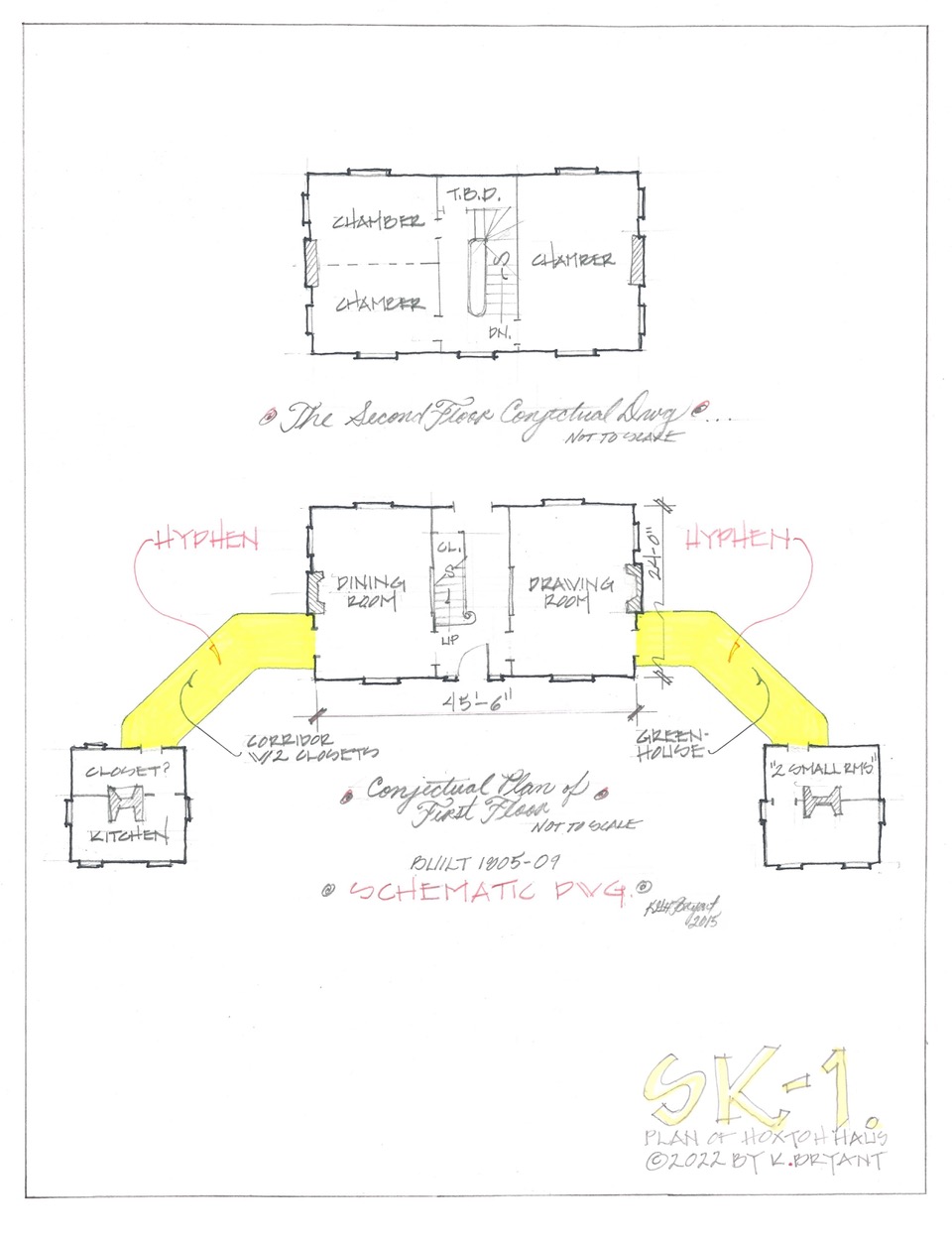

Most historians have assumed Thornton is the prime suspect. After countless hours in the Baker stacks, I knocked on the door of architectural historian Marlene Heck. Her eyes lit up whenever we talked about classical buildings. This made me smile. From her shelf she pulled coffee table books to show me old Southern houses she abhorred. Like me, she admired Thornton. By 2009 I discovered, however, that the case against Thornton is straightforward. His houses typically incorporate curvilinear elements, with a flourish similar to that of the circular porch of Collis Center. Not so with Hoxton. Its original hyphens (the loggias connecting its central block and flanking pavilions) were angled like a stop sign, which is not Thorntonesque. The good doctor would have skewered this type of classicism as too severe. And though they traveled in the same circles, Eliza loathed Mrs. Thornton. Nevertheless, Thornton remained on my radar.

As an African American I was shocked and sickened, yet somehow still intrigued, when I learned that Eliza, the woman I’d grown to adore, was a slave owner. I telephoned my aunt Rowena, then 93. She grew up in the segregated South. At Dartmouth, the best place to get a cell-phone signal was Dick’s House, the infirmary built like a country estate with a charming living room. I’d sit there, we’d talk, and I’d tell Aunt Rowena everything, from the pain of coping with discrimination to my frustration that it was taking time to feel at home at Dartmouth and even to the irony of still desperately wanting to find who designed Eliza’s house.

My search led to an 1808 real-estate ad written by Eliza that promised those seeking convenience and health “will find all combined in MOUNT WASHINGTON.” Had Eliza left me a trail of breadcrumbs?

By now I lived in the Choates, in a 1923 Dutch Colonial dormitory. Soon I began to suspect strongly that Latrobe was the architect whodunit. (His claim to fame is designing the iconic north portico of the White House.) Latrobe was so busy that he could subcontract work to architects such as Hadfield or Lovering who designed Eliza’s old townhome (Honeymoon House). Latrobe and Eliza were friends, and her aunt admired Latrobe. It’s possible she persuaded Eliza to hire him.

It was exciting to find that Eliza’s most-trusted uncle, George Calvert, had commissioned Latrobe to design his mansion. Maybe she had hired him too. Additionally exciting was an 1807 communiqué from Eliza to her stepson John Law. It discusses her overseeing the home’s progress, unusual for a woman, and supports the theory that Law influenced the choice of architect. Professor Misaph Parsa, a social historian, had taught me (as a budding architectural historian) to keep in mind the pervasiveness of patriarchy in early America, especially the South. During roundtables, Parsa’s voice would take a somber tone as he discussed the disenfranchisement of women and Blacks in the early 19th-century, and their lack of social capital. Then I thought, “Aha!—if an architect like Latrobe designed Mt. Washington, Law, a man, would not have solicited Eliza’s input. So her stepson may be key to unlocking the mystery.”

The next shock was learning that the look I’d come to associate with Hoxton was the result of a 20th-century alteration. Those Doric columns that gave her the appearance of a plantation were added in 1913 by Beaux-Arts trained architect F.H. Brooke. The effect was of a powerful preparatory school steeped in tradition. Before, Hoxton was, as Eliza’s aunt put it, “a pretty little country-house.” This was evidence against Latrobe, whose work tended to be more muscular and Neoclassical. So could it be Thornton? After all, his exteriors were in a more delicate Federal style. In that moment of inner debate, it dawned on me what was at stake. Deep down I thought if I solved the mystery I’d finally be accepted (even respected) by the good Old Boys of EHS—something I longed for.

During the next two years I spent night after night at my favorite reading spot in Baker-Berry (a 1920s library remindful of Independence Hall), navigating coursework and my search for the architect. I completed my dissertation on American architecture, graduated, and returned to Manhattan in 2008 before I carved out time to finish my investigation. I regularly trekked to the New York Public Library, where, in a reading room reminiscent of Sanborn—the College’s most exquisite Georgian interior—I was whisked back to the 18th century: The experience was like a refresher course on Colonial architecture—in NYC—that focused on the building of Washington, D.C.

By 2012 I seriously began to consider, if not conclude, that Hadfield did it. He had designed Arlington, the home of Eliza’s brother. Perhaps Latrobe subbed the work out to Hadfield or suggested Hadfield to her. Was I getting close? Invigorated, I remembered something my beloved professor, William Cook, said: “What’s most impressive is accomplishing something under unbelievable conditions.” Those words had spurred me on as a struggling architectural designer during the Great Recession.

At the library, as I searched through stacks of books, placing each with an audible thump on the table, I noticed something. A common thread in Hadfield’s buildings jumped out—his distinct design of arches. This was my eureka moment. The visual parallel of Hoxton’s various types of blind arches (shallow arched niches, some with windows) versus blind arches on the exterior of D.C.’s Old City Hall is uncanny. This quirky detail of Arlington, City Hall and Hoxton irrevocably pointed to Hadfield. In addition, Hoxton’s original front porch was capped by a stepped gable like that found on the wings of City Hall.

Still, I had no smoking gun.

Furthermore, the front porch in American architecture plays a pivotal role as a symbol of belonging, gathering, and peaceful memories. To illustrate, let’s rewind—to Dartmouth’s Homecoming weekend in 2006. It was early in my research quest, and I was running in circles. On my last ritual lap around the homecoming bonfire, I made sure to look across the Green at Collis—whose towering verandah was a mainstay of student gatherings. Its beauty, in that moment, seemed a reflection of Hoxton. I could see its columns in the distance.

My fondest moment at Dartmouth occurred the next morning. My graduate school buddies and I sat on Collis’ front porch for breakfast. Sitting with friends under those columns, the pain of bygone years of not fitting in suddenly, withered away. I was home. My secret, which still hurts too much to talk about, is that I left EHS before I graduated. I eventually went to Phillips Academy, but the hurt I bottled up and internalized about leaving Episcopal High School never went away. Now, at Dartmouth, for the first time since struggling to find my place at boarding school—I had found a sense of peace.

By 2012 I had only circumstantial evidence that pointed to Hadfield. The economy had warmed up, but the trail had gone cold. My hope of being credited with a great historical find was fading. At Dartmouth, historian Celia Naylor advised me, as I endeavored to find my way as an architect and historian, that research requires agility and an ability to focus on and expand and see both sides, now and always. “Instead for focusing on the building’s outside, put yourself in the place where the problem lies,” she once said. “Then ask where it leads.” Maybe Hoxton’s interior could provide clues. I recalled how as a child I’d walk onto its majestic front porch, press open the chic, black-lacquered door, and step inside—perpetually alone. Now I was overcome with a feeling of strength, faith in myself, and joy. It was during this leg of my research in 2013 that I came across Glenn Brown, a relatively unknown architect-historian. He’d written about Hoxton’s interior. In 1908, as secretary of the AIA and editor of its Quarterly Bulletin, he had also indexed a write-up in Architecture magazine to commemorate the 1904 reconstruction of Dartmouth Hall following a tragic fire.

Brown’s discussion on Hoxton’s superb craftsmanship led me to wonder about the treatment of the skilled enslaved Africans, who likely built the house, and the path they paved for contemporary architects of color like me.

While poring over articles by Brown, it became clear that since the late 19th century Hoxton has been considered worthy of study. As a house with a center-hall plan, it is deceptively simple. Whereas its central block is a shallow 24-by-45½ feet, the first floor has whopping 14-and-a-half foot ceilings. Brown keenly observed that all doors and windows were trimmed with distinctive ornament and enriched moldings, evidently intended to represent “Abundance, Sowing, Reaping, Pleasure, Religion, etc.” Regarding antebellum houses, Brown further acknowledged “the carpenters and builders of the day” and accommodations for, in his words “servants and horses.” Reading this I recalled how professor Cook had led me—as an architectural historian and Dartmouth man—to see the humanity of all people, especially the historically marginalized and oppressed. As I read those passages, Brown’s discussion on Hoxton’s superb craftsmanship led me to wonder about the treatment of the skilled enslaved Africans, who likely built the house, and the path they paved for contemporary architects of color like me.

And then it happened—booyah! Suddenly, while intently scanning the fine print of a 19th-century magazine column by Brown (dated October 22, 1887), at long last, there it was—the moment of truth I had been praying for.

It said, “The only facts obtainable are… [Drum roll… little to none].”

After all the back-and-forth, I never found anything naming the architect. I felt like an “astrologist,” unable to predict the future by the position of the stars. Eliza never recovered from the scandal of divorce, nor was she accepted (or respected) by Washington society again. And, as mentioned, I ultimately left EHS. What I didn’t admit, is what happened: During parent’s weekend, all new boys, me included, were forced to stand and sing “Dixie.” At 15, I had the courage to say no.

Although the architect of Mt. Washington remains unknown, since 2012 I have formally attributed it to Hadfield. But there’s a catch: It was likely a collaboration. Eliza would boast, “The house which I erected…is nearly completed.” This and other passages prove her hands-on approach in the project’s design and construction. Therefore, I also attribute it to her, a woman as an amateur architect. She had the will and wherewithal to do it herself—making her probably America’s very first female architect.

I never found the proverbial smoking gun. But in architecture, as in life, often more than finding “the answer,” the purpose is the journey: My point being that research is as much about the romance of seeking the problem, as it is about finding the solution. The complexities and contradictions of architecture, like learning to heal from the past, can be an enigma. For example, how can Eliza’s house be so beautiful, yet symbolize something so horrific like slavery? How do we reconcile this?

To paraphrase Nietzsche: “Nothing is beautiful… Nothing is true—just us,” which I interpret as we should never stop searching for what is beautiful and true.

While packing up my files I decided to locate Eliza’s and her siblings’ homes on a map. Low and behold, in plain sight—finally—was the groundbreaking discovery I’d been hoping to make. The four residences (Woodlawn, Hoxton, Arlington and Tudor Place) were aligned in a perfect beeline row stretching 15 miles end to end. What’s more, they were arranged in a descending geometric series. I double checked on Google Earth. This was no accident. It took thought. Considering surveying techniques of the 18th century, it’s amazing. The estates were likely built in a straight line (extending from Mt. Vernon, across the Potomac, into the capital) to demonstrate the owners’ significance as grandchildren of the first president. Each was no stronger than its weakest link—the “little country house” that caught my eye as a child.

“Was it a map to hidden treasure?” Instead, I found in near-perfect formation—to the south, Gunston Hall (1755), home of George Mason, the driving force behind the Bill of Rights; and to the north, Woodley Mansion (1801), former home to Francis Scott Key (who wrote a song about the majesty of war and magnificence of peace). Like stars aligned in celebration of the new nation, the four signature houses portend variations on a loose theme and a work in progress: a new Canaan known as America.

I began thinking of those landmarks as a constellation. I envisioned it in a night sky—above Hoxton, dipped in moonlight—like over Central Park when I first learned Hoxton’s secret. What I thought of was not just the stars, but also the beauty of the Payne’s grey skies: dark and mysterious—as gorgeous as the glow of individual stars, as wondrous as “one thousand points of light,” because in the space between stars, beyond those points of light, exists—a million suns… a trillion worlds.

Eliza was never able to construct a mansion as impressive as her brother’s and sisters’. Yet Hoxton perseveres. Children have been educated under its roof for almost two centuries. In 1831, Eliza died at age 55. In the end—after all their squabbling and bickering, her ex-husband reminisced about how, long after their separation, as he lay sick, she burst into his room and insisted on nursing him to health. Their love had endured.

Kenneth Bryant is a New York City and Norfolk, Virginia-based residential designer. He is a protégé of David Easton and Albert Hadley. He is also founder of ADEPT (Alliance for Design Equity in Practice & Theory), a nonprofit focused on improving marginalized communities through innovative walkable and sustainable design, and an adjunct professor of architecture at Hampton University.