College Park

Set aside by College trustees in 1854; planted 1867-68; students cleared paths and improved the area 1879-82

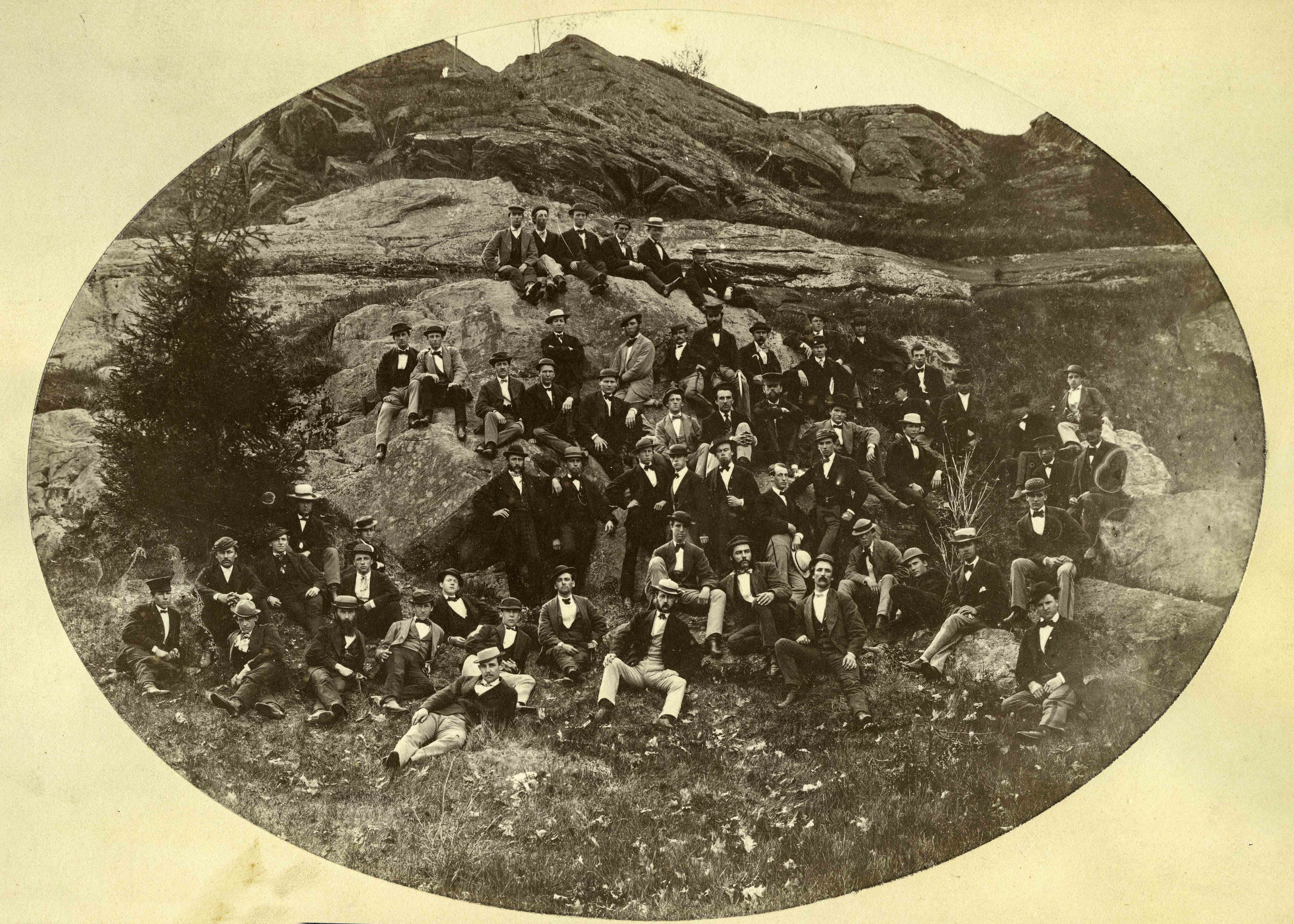

In 1854 College trustees decided “the field north of the College grounds in which the observatory is situated be appropriated as college grounds and never more for pasturage.” It isn’t clear what specific concern, if any, prompted them to set aside the romantic landscape that became College Park and one of Dartmouth’s greatest treasures. Perhaps it was nothing more than the influence of the Victorian-era popularity of parks and park-like settings. As the College’s 1869 centennial approached, trustees called for a general improvement of the entire campus grounds and hired the Boston landscape firm of Lee and Follen to prepare a plan to improve the park lands. Nothing came of the Lee and Follen design, but Judge Joel Parker, class of 1811, responded with a suggestion of his own. Parker wrote the following in an 1867 letter to President Asa Smith.

If the intention is to make a College Park (in contrast to a private gentleman’s grounds), as I understand from your letter, it appears to me that the main article should be trees—many of them trees which will grow to a large size—and finally make a grand old woods—shrubbery of course here and there, to a limited extent, and a few creeping plants to cover some of the rocks—not all.

Parker followed through on his suggestions, and between 1867 and 1868, he sent some 15,000 young trees to the College from a nursery in Anger, France, and contributed $1,000 to purchase additional lands to expand the park. As planting began, much of the park’s land, particularly that area closest to the College buildings, still remained bare from the clearing done in the earliest years of the school. Judge Parker made clear in a letter to President Asa Smith that the president had the authority to “ask for more” if 15,000 seedlings proved too few. Apparently, it proved far too many. Not all found their way into the park. The College moved hundreds—temporarily it thought—to land at the corner of East Wheelock and North Park streets, but ended up cutting them down decades later. Others were planted elsewhere on campus. The task of overseeing the planting of the remaining thousands fell to Daniel Blaisdell, the College treasurer. Blaisdell took the expeditious approach, but ran afoul of William Smith, the president’s son. William wrote to his father after learning that Blaisdell had simply instructed freshmen to dig a hole and plant “wherever they think a tree should stand, all over the hill,” with no thought to design. Smith admonished his father.

It seems to me a pity to use up $200 in this inartistic way. There should be an eye to a future laying out of the ground, to the effects of harmony & contrast, in form [and] color. There should be a vista here, a clump of rich evergreens there, a disposition of the light & graceful, the somber & stately, such as an artist could make. I should certainly consult with Judge Parker or with some gardener & see if this could not be effected without undue expense.”

But once the centennial passed, the beautification efforts languished until a decade later, when President Samuel Bartlett took a renewed interest in the project. While Bartlett’s successor, William Jewett Tucker, constantly invoked the College’s history and developed new traditions to strengthen ties between Dartmouth and its students, Bartlett was Dartmouth’s first president to take an active role in creating places and events to bind the school and its students together. Bartlett appears to have proposed a plan, which was worked out by two faculty members, professors Robert Fletcher and A.S. Hardy, to cut carriage roads and walking paths through the park and to furnish the park with rustic bridges, benches and a summerhouse or two. The College was too poor to hire workmen to do the work, so Bartlett presented his ideas to the students and suggested they might spend their free Wednesday and Saturday afternoons clearing the brush and building the new roads and paths. Students responded enthusiastically, at least initially, and began the project under Fletcher and Hardy’s direction. The Dartmouth for September 5, 1879, described a spirited gathering of students eager to begin the work.

The enthusiastic meeting of the College, Wednesday afternoon, augurs well for the carrying out of the plan of beautifying the College Park. After the eloquent addresses of President Bartlett and Professor Sanborn on the matter, there is but little to say. Everyone who has walked over the hill back of Dartmouth Hall has asked himself, “Why is not this spot improved and by a little work made the beautiful part of one of the prettiest villages in New England.” It is a wonder that no energetic steps have been taken before...We would rather that the College could do it without the assistance of the students, but inasmuch as this is not contemplated, we cordially indorse [sic] the idea of asking them to help in the work personally.

By the time the first season of landscaping was completed in November 1879, the paper reported the following.

Most of the walks that were planned have been completed….One carriage drive way has been made, one or two bridges constructed, and rustic seats placed along the walks. In the early spring a summer house will be built, and with a little more work on the walks, etc., we expect to be able to enjoy afternoon rambles and evening strolls in a picturesque and beautiful park.

Work resumed the following May. At least two summerhouses, one metal and one a frame structure put up by the College carpenter, were erected on the high ledges that overlooked the Bema. In spite of regular appeals to students to maintain the cultivated portion of the park and to continue the improvements deeper into the site, interest in the project slowed, then disappeared. At the close of the nineteenth century, a brief flurry of activity renewed attention on the site. Judge Horace Russell, class of 1865, gave $175 in 1896 to repair the walks and paths, restore the summerhouses and build another “rustic” bridge. (Russell included an extra $25 to re-carve the inscriptions on the tombstones of the College’s early presidents.)

A 1931 survey of College Park determined that almost half of the trees planted were Norway spruces, with fewer numbers of European larches, Scotch pines, Austrian pines, Norway maples, English oaks and elms. The largest tree identified in the survey, a European larch that stood in the approximate area where the Fairchild Science Center is located, measured 4 feet, 4 inches in diameter and stood 98 feet tall. By this survey, the black alders and European white birches Parker sent had disappeared from the park. Through the 1930s the College pruned the mature trees and cleared away new growth and dead material to open up the land and reduce the fire hazard. But a September 1938 hurricane destroyed so much of the park that, as it was explained in The Boston Globe, Dartmouth suddenly found itself in the lumber business. The College put up a sawmill in College Park and cut more than 500,000 feet of lumber.

When the College’s administrators urged College Park’s development in the nineteenth century, they imagined it as the campus centerpiece. But during the twentieth century Dartmouth grew to the north and west, and for the most part turned its back on College Park except to carve an occasional road or parking lot from its edges. As the College identifies new sites for much needed expansion, this important open space has begun to figure more prominently. Construction of new undergraduate and graduate housing on the park’s southern and eastern boundaries means the park will become a shortcut through to the center of campus, which may require the construction of new paths or the installation of gateways that more clearly delineate entries and circulation. Dartmouth’s master plan currently calls for limited development along the park’s edges, with the continued preservation of its interior as a rare and beautiful place for peaceful retreat.

Bema

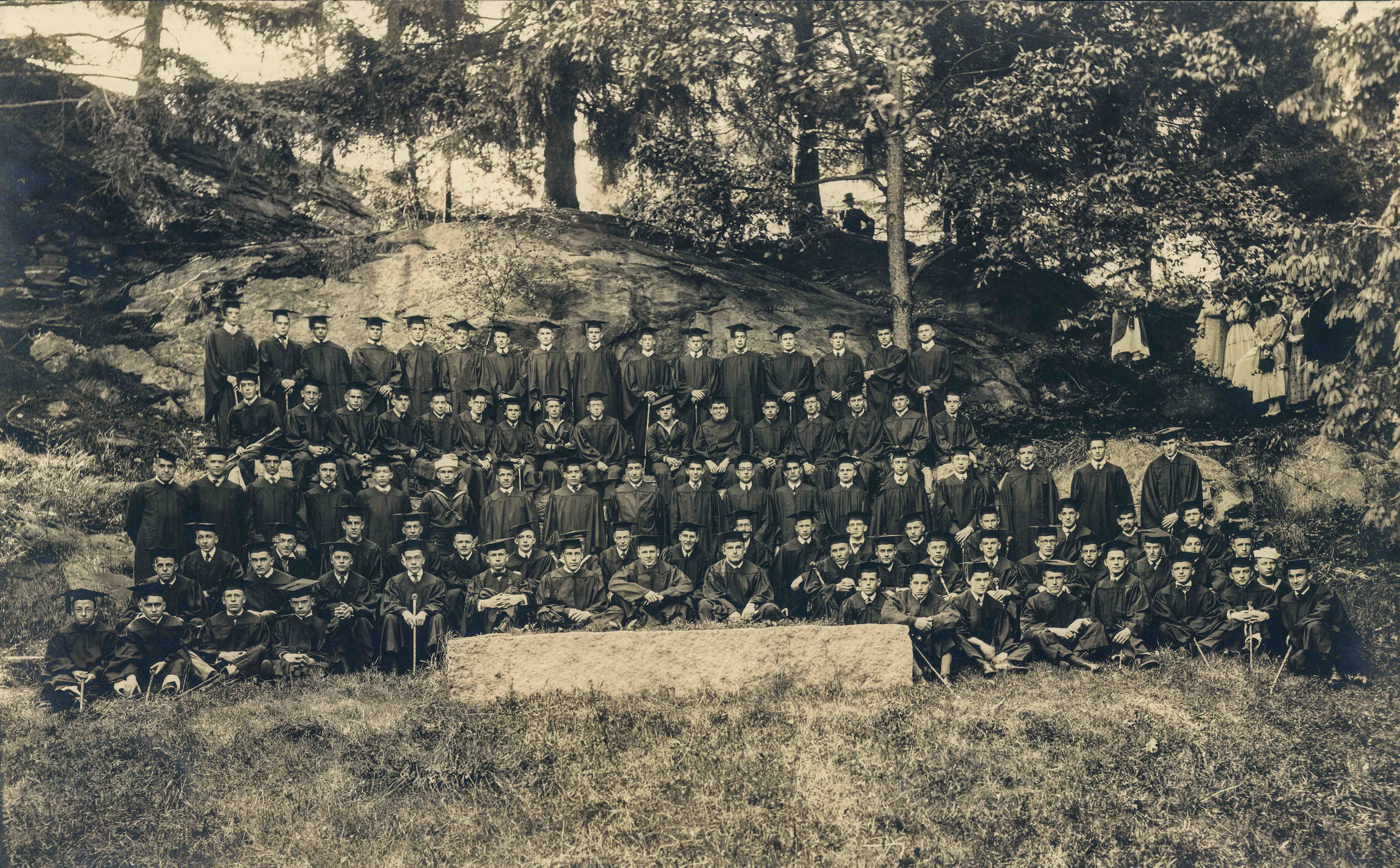

Built by students; begun 1882

The word bema is Greek, and means a platform for public speaking. Plans for the Bema grew out of President Samuel Bartlett’s efforts to improve the College Park lands, and in fact, it seems excitement over construction of the Bema drew workers away from clearing and improving the park’s lands. Nearly four years after work began on improvements in College Park, the March 31, 1882, The Dartmouth reported the following.

The Seniors are making good headway toward the construction of an amphitheater in the Park for Class Day exercises. The cliff that rises abruptly on the west side of the open space, commonly known as the “Freshman Gallows,” is being dug away, and a sort of Bema made. Terraces will be built, and the place cleared of unsightly shrubs and brush, rendering it easier for both audience and speakers to get the most of the occasion. Delegations of the class are working every afternoon, and by the end of the term the work will be nearly done.

As the College outgrew Webster Hall, it held its first outdoor Commencement in the Bema in 1932 and continued to do every year until the ceremony moved to the Baker lawn in 1953. The first outdoor Convocation took place in the Bema in 1943, and it is still the site of Class Day exercises on the day before graduation. It tells us how far the fortunes of College Park had fallen by 1965 that the Bema area was considered as a possible building site for new dormitories. The College decided to place the buildings, later named French, Hinman and McLane halls, at the far western edge of the campus—the River Cluster—rather than in the midst of College Park.

Robert Frost statue

George Lundeen, sculptor

Robert Frost, class of 1896, keeps vigil from his seat on a block of New Hampshire granite. The bronze, life-size figure has startled many a visitor in College Park.

Bartlett Tower

Built by students with assistance from College workmen; 1885-95

Tucked away in College Park and locked up against entry, Bartlett Tower rarely rates a mention on campus tours. Most students and alumni would be surprised to hear that when it was constructed, Bartlett Tower was intended to be one of the College’s main attractions. One enthusiast predicted the following.

When completed the tower will present a commanding appearance and no other object about the town will remain for a longer time in the memory of visitors. From its top will be derived a grand view of Old Dartmouth and the green hills that encircle it. The grey haired Alumnus will come back and from its top will gaze fondly down at each familiar place, and in fancy will live once more the gay old college days and will imagine himself once again the studious Freshman or gory Sophomore.

Because the stone tower went up near the storied “Old Pine,” the College’s symbol (look for it on top of Baker Tower and set into the north wall of the Hop), some mistakenly believe Bartlett proposed the tower to replace the tree, which by the mid 1880s was in decline. The pine, which survived the early clearance of the College’s lands, became an important feature in the senior graduation rituals in the early 1840s. (Late nineteenth-century students were told the tradition began when three Indians who were about to leave Dartmouth, gathered around a pine and sang a song that began with a melancholy, “When shall we three meet again.” A later line answered, “When around this youthful pine moss shall creep and ivy twine,” all of which has a decidedly Victorian tone about it.) In an allusion to the College’s early history as a school for instructing Native Americans, in the mid nineteenth century seniors began to gather around a large, old pine during Commencement week and pass around a pipe representing a supposed Indian custom that signified cooperation and friendship. The ceremony grew more elaborate until a speech and a poem accompanied the passing of the pipe. Hit by lightning in July 1887 and its largest branches ripped off in a June 1892 storm, the decaying tree was cut down in a ceremony on July 23, 1895. The Dartmouth reported, “In its glory it was very majestic and its stately symmetry and commanding position made it a conspicuous mark for miles around. It was probably 125 years old, and was the last of the primeval forest.” Former President Bartlett described it as undoubtedly dating “back to a period earlier than the foundation of Dartmouth College in 1769 and was part of the pine forest which then covered the plain and adjacent heights.” The College sent the tree to a sawmill across the river in Norwich, Vermont, and had the wood used to craft a chair for President Tucker, a mantel for the Butterfield Museum that was then under construction, and the case for a tall-case clock that still stands in the president’s office. A few seniors still gather each year around the stump and pass a pipe around.

But when the tower was formally renamed Bartlett Tower in 1915, Bartlett’s son spoke at the rededication and suggested the idea for a “castle tower” had come from him and the structure was intended more as a garden folly.

The work of the president in those days was full of irksome detail.…Late afternoon found him weary and often sad. In the company of the big oak stick and the “little b’y” [the son], he sought his daily solace out of doors.…Hand in hand we came to this rock one day, and the little boy pictures a castle tower on what seemed to him a frowning precipice, and begged that there might be one. The boy’s whim took the man’s fancy and grew into a plan for successive classes to build such a tower in sections with their own hands.

President Bartlett first proposed the project at chapel services in the fall 1884, suggesting that College Park could be further improved by the construction of a stone tower placed on the site’s highest ground and put up in a “medieval” style. While students endorsed the newest addition to the developing park, lack of funds meant that most of the cost and all of the labor would fall to them. An article in the October 17, 1884, urged men to step forward.

To such a plan no one can object; all will hope that it may be carried out, but the question is, how is it to be done? With money needed in all its departments, the College cannot afford to spend much for an ornament, and the President suggests that the work may be done by the students. With proper direction and enough to take hold there would be nothing very difficult, and we can understand how the work might be made quite attractive. We trust something may soon be done about the matter. The students should express in some way their opinion of the scheme, and their willingness or unwillingness to do their part towards carrying it out. An opportunity is now offered them for erecting a lasting monument of their devotion to their Alma Mater.

The following May, The Dartmouth announced the class of 1885 would prepare the foundation for a tower 12 feet in diameter and 75 to 80 feet high and on its Class Day would lay “with appropriate exercises,” the stone inscribed with their graduation year. The plan was for each class to put up at least 10 feet of the tower each year, then on its Class Day, lay the memorial stone carved with its class year. The writer had no doubt that “Upon the foundations thus laid each succeeding class will no doubt build, and the laying of a stone each Commencement to mark the work done by the graduating class will make a very fine Class Day part.” A new tradition, it appeared, had begun. But the students’ enthusiasm was short lived.

By 1887 the project began to falter, largely over costs but also because some perceived social pressure to support the project. “Once more the question arises, Will the Senior class continue work on the tower,” one article in The Dartmouth began in October of that year.

There appears to be a strong sentiment in the negative, for reasons which are well known to those acquainted with what has transpired in College during the three past years. Senior year is one in which taxes of all kinds multiply with wonderful rapidity; and inasmuch as we have been advised time and again by the College authorities to bring unnecessary expenses to the minimum point, the class might well be excused from levying on its members the $7 or $8 per capita which would be necessary to add the usual ten feet to the tower. Again, there are other than economic reasons entertained by a large part of the class in consequence of which they do not care to further the project. Not a few of the members feel that justice has been unduly influenced in dealing with matters pertaining to them and, thinking that the source of that influence is with those most interested in having the tower finished, consider it a good opportunity to retaliate by refusing to cater for their wishes. But there is another side to the question, which, if considered in a light undimmed by class or personal prejudice, will show conclusively that the class would some day regret it if it does not make the addition expected it.

To build or not to build: The question arose each year after. From 1888 on, students hired masons to do the work. Members of the 1889 class admitted that, “We have heard several members of the last two classes claim that the tower is a nuisance and that the money spent in building it is thrown away,” but appealing to their classmates’ sense of pride and tradition, they urged support. The class of 1890 debated whether they should be known as the first class not to add to the tower or later regret being the only class that hadn’t taken part in its construction. As the 1892-93 school year began, The Dartmouth alerted its readers that “the Senior class will soon be called upon to consider the advisability of adding a few feet to that graceful structure on the hill,” and continued with the protest.

It has become an inexplainable precedent for classes to levy a tax for the purpose of enlarging the labor market of stone masons of this vicinity.…The whole subject of the tower seems to us to be the most sentimental farce in the college category. If the class of 1893 is to take any action in the matter, the best thing she can do is to confer a benefit upon succeeding generations by putting a cap on the structure which no Hanover cyclone can remove.

The classes of 1893 and 1894 settled the matter by combining their efforts in the spring of 1893, and masons hired by the class of 1894 added the final courses in their graduating year. All that remained for the class of 1895 was the addition of a copper cap and the project ended.

On June 21, 1915, responding to a request from Connecticut alumni, the trustees voted to name stone tower in honor of President Bartlett. The structure was rededicated as part of Class Day exercises in June 1915, and that same day the College unveiled a plaque attached to the tower with the following inscription.

The erection of this tower as a landmark more enduring than the Old Pine was suggested by Samuel Colcord Bartlett, eighth president of Dartmouth College. It was built by members of the successive undergraduate classes from 1885 to 1895.

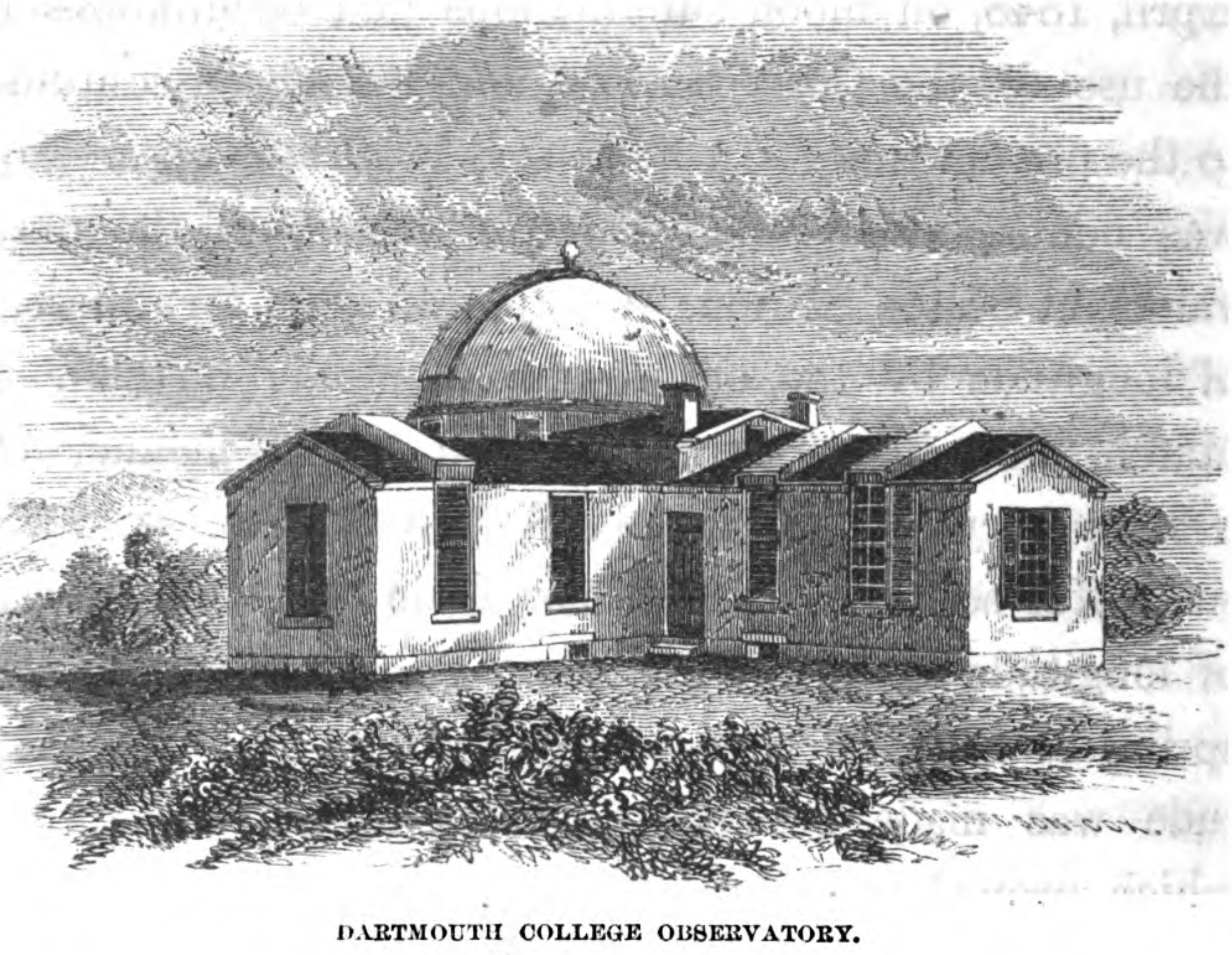

George C. Shattuck Observatory

Ammi Burnham Young, 1854; 1909; 1938

Soon after Ira Young, class of 1823, joined the College faculty in 1833, he began to acquire the specialized equipment he needed to teach astronomy. When Young received an appointment as professor of astronomy in 1838, he approached the trustees with another request for astronomical tools. They approved, and Young used these instruments to furnish his new lab in Reed Hall. (Thanks in great part to Ira Young, the College owns one of the oldest and largest collections of historic scientific instrument in the country.) Eight years later, he received approval to purchase a German-manufactured 6-foot refracting telescope, but once it arrived Young realized there was no suitable place to mount it. As an interim solution, trustees authorized Young to build a two-room structure in the garden of his house to hold the telescope. Acquisition of the telescope drew so much student interest in astronomy, that Young again appealed to the trustees for funds to erect a new permanent observatory where the telescope could be correctly installed and used. While he waited for a decision, Ira asked his brother, Ammi (the designer of Wentworth, Thornton and Reed halls) to draw up an observatory design. In December 1847 Ammi Young sent three elevations, two plans and a sheet of working drawings, which Ira used to solicit construction estimates and, it appears, a donor for his observatory.

In 1852, after meeting with Ira Young, Boston physician Dr. George C. Shattuck, class of 1803, gave the College $7,000 to build the observatory, and stipulated that the College match his donation with $4,000, that Ammi Young design the observatory and that Ira Young be sent to Europe to buy additional books and scientific equipment needed to get the operation up and running. With funds now guaranteed, Ira Young returned to the observatory’s design. In January 1853 Ira wrote to Ammi with some suggestions for modifications to what he terms the “old plans.” Ira noted his suggestions were minor and would not, in his opinion, require a new set of drawings. In the main, he didn’t quibble with the general design submitted by his brother, but over several pages of notes, Ira Young demonstrates a sure sense of what he wanted in terms of scale, materials and layout; he was particularly interested in the construction and design of the dome. Ammi Young replied a little more than a month later that the papers sent by his brother “have laid so long on my table without finding the time at my disposal necessary to consider them” and given the constraints of time, he was “compelled to get off with the least possible amount of time in their consideration.”

When Ira Young left for Europe soon after, he turned responsibility for the project to his colleague, Professor Oliver P. Hubbard. Trying his best to keep the project on track, Hubbard wrote to Ammi Young inquiring about a number of matters, but fared no better than Ira Young had. Ammi replied with a brisk letter stating that “business here [Washington, D.C.] compelled me to dismiss the subject actively from my mind and I supposed I should have nothing further to do with it.…I have no copies of the plans or papers relating to the building and the matter being almost entirely out of my mind, I cannot give you any very definite instructions in regard to it. You must use your own judgement in the matter.”

A small job back in Hanover, even one for his brother, no longer held any interest for Ammi Young. Named the first supervising architect of the U.S. Treasury Department in 1852, Young was now in charge of all federal architectural construction and far too busy to consider the observatory project beyond the work he had already done. He gave brief, undetailed answers to his brother’s questions and suggestions, provided a drawing of a brick cornice which “must answer for the present” and promised to send some lithographs of his custom house projects that showed construction details and “perhaps some other things that may be of use to you.” The building completed in the fall 1854 was a small, simple brick structure with faint classical details—most of it designed in 1847.

You can still find meteorological instruments in the yard around the observatory, some of them perhaps brought back from Ira Young’s 1853 European shopping expedition. Dartmouth introduced meteorology into the curriculum in 1849, the same year the Smithsonian Institution started gathering meteorological data from around the country. Ira Young explained the following to his benefactor, Shattuck.

In Meteorology, we think it very important that we should be furnished with a complete set of the standard instruments that have lately been introduced under the direction of Professor Guyot [Arnold H. Guyot, who was working with the Smithsonian to distribute meteorological equipment and train observers who would send their findings to Washington], at some of the principal points of observation through the United States. These, I believe consist of Barometers, Thermometers, Hygrometers, Anemometers, and Rain Gauges.

Young apparently returned well stocked from his travels, for in October 1853 he began monthly submissions to the Smithsonian. These reports continued for many years after Young left for Princeton in 1857.

Installation of new instruments in 1909 required minor structural changes to the building. When these were under way it was discovered, among other things, that the foundation had been poorly laid and part of the underpinning including a reused millstone. The observatory received an addition in 1938 to house new equipment. It remains much in use, both for College astronomy courses and public stargazing. But for research purposes, Dartmouth faculty and students now head to Kitt Peak, Arizona, to use the two telescopes there operated by Dartmouth in a consortium with Columbia, the University of Ohio and the University of Michigan.

When the nearby Wilder Physics Laboratory was constructed in 1898, astronomy was given a recitation room, library and office in the new facility. Their quarters have grown considerably, but the astronomy department still calls Wilder home.

Senior lecturer Marlene Heck’s work focuses on the architectural and social history of ‘America in the age of Jefferson.’