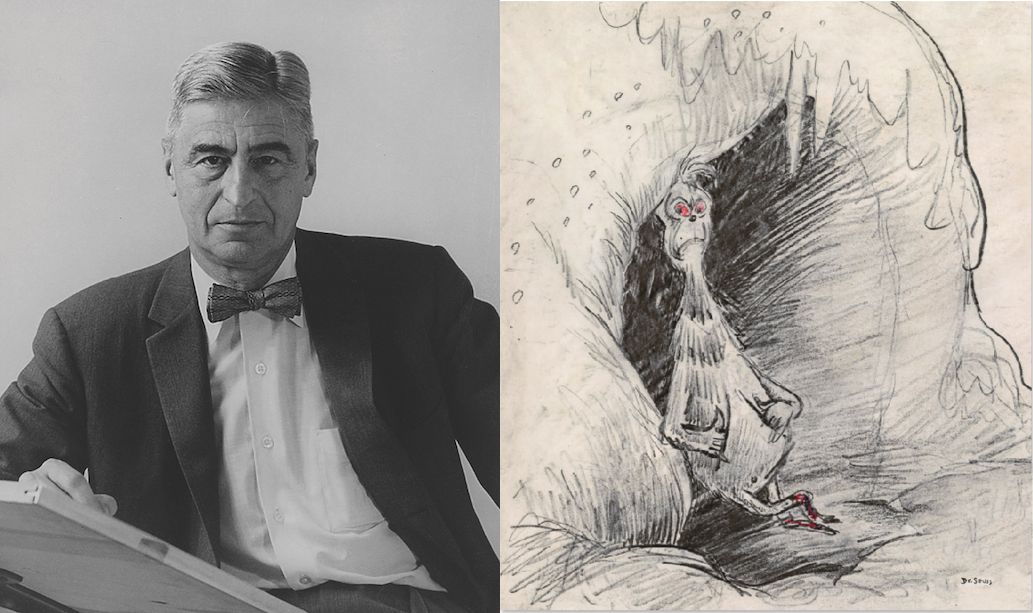

The Grinch, it can be said with some certainty, is a Dartmouth man. Although the Christmas-stealing grump would not make his literary debut until 1957 in How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, you can trace his pedigree back more than three decades to the humor magazine, Jacko. It was here, in 1923, that the Grinch’s creator, a 19-year-old English major named Theodor Seuss Geisel—his Dr. Seuss pseudonym still years away—was finding his footing as a writer and artist.

It wasn’t easy. “I began thinking that words and pictures, married, might possibly produce a progeny more interesting than either parent,” Geisel recalled, “[though at] Dartmouth, I couldn’t even get them engaged.”

But for the November issue that year, Geisel had an artistic epiphany, drawing a page of beasts he called Bo-Boians, the earliest incarnation of fantastic creatures to come. While there’s no Grinch among them, the character’s ancestors are visible in the cow-like Heumkia, the bowtie-wearing Dinglebläder, and the pensive Panifh. There’s no mistaking elements that would make their way into Geisel’s distinctive style, including wide eyes and knowing grins—and rather than hooves, the Heumkia appears to be wearing footed pajamas, with one foot casually cocked over the other, a very Grinchian pose.

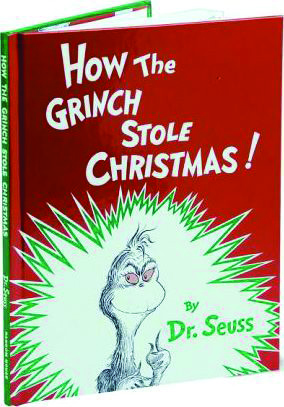

By the late 1950s, however, the name Dr. Seuss was more than a mere pseudonym. It was practically a brand, a sign of quality kid-lit notable for spry verse, distinctive art, and—perhaps most important—an absolute respect for children as readers. But although the 13 books Dr. Seuss had written so far all sold respectably, Geisel was still earning a living mostly through his work as an advertising illustrator. All that would change in 1957, when Geisel published not one, but two blockbuster Dr. Seuss books in less than 12 months. In April it was The Cat in the Hat, and in December came How the Grinch Stole Christmas!

The first print run for the Grinch was 50,000—a large run for a children’s book. Oddly, there were two other children’s Christmas books published in 1957 that tell stories of Christmases that were nearly canceled: Ogden Nash’s The Christmas That Almost Wasn’t and Phyllis McGinley’s The Year Without a Santa Claus. Neither could touch the Grinch. Within days of its publication, it was clear Dr. Seuss had created an iconic Christmas tale.

The first print run for the Grinch was 50,000—a large run for a children’s book. Oddly, there were two other children’s Christmas books published in 1957 that tell stories of Christmases that were nearly canceled: Ogden Nash’s The Christmas That Almost Wasn’t and Phyllis McGinley’s The Year Without a Santa Claus. Neither could touch the Grinch. Within days of its publication, it was clear Dr. Seuss had created an iconic Christmas tale.

Geisel, who had struggled to make the ending to this story as nonreligious as possible, was amused to find parents, critics, and religious leaders hail the book for its moral and ethical point of view. “Ministers are reading a lot of religion into it,” Geisel said, practically rolling his eyes. “Ha! You can fill a vessel up with whatever you want to.”

But he agreed that there was probably a lesson or two that could be learned in the pages of How the Grinch Stole Christmas! “Children have a strong ethical sense anyway,” he said. “They want to see virtue rewarded and arrogance or meanness punished….If the Grinch steals Christmas…he has to bring it back in the end.”

Beyond the obvious right-vs.-wrong morality of returning something that had been stolen, the real moral message behind How the Grinch Stole Christmas! could probably be found in its stance on the commercialization of Christmas—and more broadly, on the misplaced desire to equate happiness at the holidays with the acquisition of material things. If, as he said, Geisel had truly written the Grinch’s story to “see if I could rediscover something about Christmas that obviously I’d lost,” then he perhaps found it in one of the Grinch’s most memorable tercets:

Then the Grinch thought of something he hadn’t before.

Maybe Christmas, he thought…doesn’t come from a store.

Maybe Christmas, perhaps…means a little bit more!

When two little boys named David and Bob Grinch wrote to Dr. Seuss complaining that they were picked on every Christmas because of their last name, Geisel immediately wrote back defending the Grinch. “I disagree with your friends who ‘harass’ you,” he responded. “Can they understand that the Grinch in my story is the hero of Christmas? Sure…he starts out as a villain, but it’s not how you start out that counts. It’s what you are at the finish.”

Asked later which of his two superstar characters he’d rather have as a dinner guest, Geisel didn’t hesitate: “I’d like [the Cat in the Hat] because he’s against law and order. The fact that he cleans up at the end is just an easy out; he really prefers a mess. So I wouldn’t like to have him here—I’d rather visit him in his house,” said Geisel. “[But] the Grinch? Personally, I like him.”

Indeed, Geisel would always call the Grinch his favorite character. Maybe there was just a hint of the Grinch in Dr. Seuss himself—both, in fact, had undergone a bit of an existential crisis when it came to Christmas materialism. “Frankly, I was annoyed at what was happening at Christmas,” Geisel said later. As he stood before the mirror brushing his teeth on the morning of December 26, 1956, he caught sight of a face scowling back at him. “It was Seuss!” Geisel exclaimed. “So, I wrote a story…to see if I could rediscover something about Christmas that obviously I’d lost.” It was little wonder that Geisel was somewhat protective of the Grinch. “I did this nasty, anti-Christmas character that was really myself,” he said later.

Geisel was inclined to be skeptical when, in early 1964, he received a note from an old friend who wanted to discuss turning the Grinch into an animated cartoon. It wasn’t the first time such an entreaty had been made, but this plea was different. It came from someone Geisel knew and respected—someone he’d worked with during World War II and who knew exactly what he was doing. “Maybe you don’t think I can draw your character,” read the note, under which was a nearly perfect rendering of the Cat in the Hat to prove otherwise. And underneath that was the crabbed signature of Chuck Jones, who had helped bring Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, along with scads of other screwball characters, to international prominence for Warner Brothers.

Jones, then 54, had recently been let go from Warner Bros., after more than 30 years of turning out one iconic cartoon after another for the studio. Now he was in charge of MGM Animation, where he was revamping the shopworn Tom and Jerry series. Two decades earlier he and Geisel had collaborated when they created more than two dozen Private Snafu morale-building cartoons when they were in the army during WW II. Knowing Geisel as he did—and well aware of his penchant for perfection—Jones knew it was going to be a tough sell and decided to take on the task in person, driving from Los Angeles to Geisel’s home in La Jolla, California, to take on Dr. Seuss face-to-face.

Geisel’s initial strategy was simply to stonewall. “He had planned that we’d talk about old times,” Jones recalled, “and then I’d go home.” But Jones was persuasive. “I told him it was time to put Dr. Seuss on television,” said Jones, who was as passionate and as meticulous about animation as Geisel was about writing children’s books. Like Geisel, Jones had put serious thought into what did and didn’t work in his craft and had even developed a series of hard rules he expected his designers and animators to follow. Geisel could respect that kind of discipline and eventually wilted under Jones’s enthusiasm. “I decided that if I was going to go on TV, I’d better do it before I’m 70,” Geisel said later.

Ever protective of his creation, Geisel finally agreed to allow the Grinch on TV under the condition that he would be permitted to serve as a credited producer of the film—mainly so he could keep an eye on the production. The two men shook hands, and Jones left satisfied. “I climbed the mountain to meet this wonderful hermit and persuaded him to allow the Grinch off the hill,” said Jones, who then went to work on the character designs and storyboards he would need to sell the show to a sponsor.

It took two months to storyboard The Grinch. Geisel and Jones worked together closely, with Jones making regular trips to consult with Geisel over the Grinch’s design and Geisel shuttling to Jones’s offices at MGM to help develop the storyboards. For the most part, the two were in sync, falling back into the collaborative rapport they’d developed in the Army.

The only real disagreements had to do with the design of the title character. Color was the first issue to be resolved. The book’s illustrations were black-and-white. Geisel had used color only for the Grinch’s eyes—a burning red. After much discussion, the Grinch became green. Jones later confessed that the Grinch’s hue was inspired by the color of every rental car he had driven around La Jolla that summer.

Geisel would always call the Grinch his favorite character. Maybe there was just a hint of the Grinch in Dr. Seuss himself.

Color decisions aside, bringing any character from the page of a book to an animated cartoon required serious thought. On the TV screen, the Grinch couldn’t be just a series of poses, as he was on the page. Geisel and Jones had to think about how he moved and walked and sat and frowned. The two passed drawings back and forth for some time until Jones—exercising a rare veto authority—approved the final design. “Ted was very patient with me. He felt that my Grinch looked more like me than his Grinch,” said Jones. “Well, something had to give, so we ended up with a sort of mélange of all the Grinches.”

With the storyboards complete, Jones began the thankless task of carting his boards around town to meet with potential sponsors, displaying the storyboards on an easel as he enthusiastically acted out scenes before rooms full of doubting candy company executives. For a while, Geisel tagged along to watch. Jones would recall he “kept seeing [Geisel’s] poor face” as they were rejected by one executive after another. Finally, he told Geisel to stop attending the pitch sessions. Jones remembered approaching 26 uninterested sponsors, including Nestlé and Kellogg’s, before finally finding a home for the Grinch with the Foundation for Commercial Banks. Jones could barely contain his amusement at the irony. “You have to be kidding!” Jones wrote later. “The bankers bought a story in which the Grinch says, ‘Maybe Christmas doesn’t come from a store’?! Well, bless their banker hearts!”

Their backing secured, Geisel, Jones, and the crew at MGM ramped up production. Geisel had made it clear from the start that he didn’t want the Grinch to look “mass-produced,” with the assembly-line animation typical of most television cartoons. Jones assured him that there would be no scrimping on the production. Whereas an average episode of the prime-time cartoon, The Flintstones, might use 2,000 individual drawings in 30 minutes, Jones promised that How the Grinch Stole Christmas! would utilize 25,000. Jones also vowed there would be no hastily assembled cut-and-paste backgrounds, and he called in an ace: his former colleague from Warner Bros., the designer and background artist Maurice Noble, whose panoramas had given Road Runner cartoons their magisterial sense of desert space.

Noble admitted to being starstruck. “I was an admirer of Ted Geisel,” he said, “but I loved Dr. Seuss.” Still, he too would go round and round with Geisel, arguing about the look of the backgrounds. Noble tried to explain that backgrounds had to extend well beyond what Geisel had drawn on the page and had to flow logically into each other from scene to scene. “You have to enrich the design,” explained Noble. “You’ve got to give it more schmaltz, and this is where I’d run into difficulty with Ted. But you don’t argue too long with God,” he recalled. Noble would eventually produce more than 250 backgrounds for the Grinch, more than twice the amount used in the typical 30-minute cartoon.

While Jones intended to stay as faithful as possible to Geisel’s original story, Jones estimated it took about 12 minutes to read aloud. For TV, the story would have to fill a running time of 24 minutes. Neither Jones nor Geisel wanted the story to feel artificially padded, so Jones suggested they spend some time using the character of Max, the Grinch’s put-upon dog, as “both observer and victim, at one with the audience.” Geisel, who already loved the character, enthusiastically agreed, saying Max was “Everydog—all love and limpness and loyalty.”

The remaining time would be filled with songs—and here Geisel was delighted to take on the task himself, writing lyrics for the Christmas-loving Whos and the Christmas-hating Grinch, while Broadway composer Albert Hague wrote the music. Sometimes writing by hand, sometimes typing them out neatly, Geisel filled page after page with snippets of lyrics, clever turns of phrase, and—more often than not—lots of long blank lines to fill in later, when he could think of a good rhyme.

The songs for the Whos were easier, mainly because Geisel could make up what Jones called “Seussian Latin” to fit his rhyme schemes. Initially, Geisel had written a long Christmas concert, in which the Whos conversed with each other in their own language, but he abandoned the idea as overly complicated. Instead, he focused on an opening carol called “Welcome Christmas,” combining both English and Seussian Latin. Geisel started off writing “Dah Who Deeno!” then crossed it out in favor of “Noo Who Frobus!” After a bit more fussing, he would finally arrive at “Fahoofores, Dahoodores” as the refrain. “[It] seems to have as much authenticity as ‘Adeste Fideles’ to those untutored in Latin,” said Jones encouragingly.

It was the Grinch’s song, however, that Geisel intended to be the showstopper, coming at the moment the Grinch actually steals Christmas, oozing around Whoville to poach their gifts and decorations. “You’re a grizzly, ghastly goon,” Geisel wrote at the top of one page, then played around with a few rhymes, finally circling “dried up prune.” But then, after writing “You brush your teeth with turpentine,” he scribbled the entire page out darkly, a false start.

Other times, he would write out couplets—some of which rhymed, some of which didn’t—to see if anything amused him enough to remain intact through draft after draft. While the rhyming couplet “Mr. Grinch…We don’t adore you, Mr. Grinch, we ABHOR you,” would be discarded, he was delighted with the nonsensical—and nonrhyming—“You nauseate me, Mister Grinch. With a nauseous supernaus.” Whatever it meant, Geisel liked it; it would stay. Meanwhile, on yet another page, he struggled to find the closing lines to follow an opening couplet he liked, inserting long blanks to be filled in later.

You’re a foul one, Mr. Grinch

Oh, you really are a punk.

You’re as _________ as a_________

You’re as _________ as a _________

Down the right-hand side, trying out words, Geisel had written “contempt” and “contemptible,” neither of which he was happy with. This page, too, would be abandoned, with the exception of three words Geisel had written in, almost as an afterthought, to rhyme with “punk,” and which he would use memorably in the final song: “stink stank stunk.”

Geisel eventually completed the Grinch’s song, “You’re a Mean One, Mr. Grinch,” as a tour de force of over-the-top, gross-out images—a bad banana with a greasy black peel, a dead tomato with moldy purple spots, a sauerkraut-and-toadstool sandwich—that made the Grinch seem even more deliciously nasty than he had in the book. With the addition of the Grinch’s song, the animated feature suddenly transcended its source material, giving the cartoon its own unique place in the Dr. Seuss oeuvre, beyond that of a mere adaptation.

In his notes for the Grinch’s song, Geisel had written that he wanted it sung in a “very low, hoarse gravelly basso.” Jones had already hired 78-year-old horror movie icon Boris Karloff as the narrator and to provide the speaking voice of the Grinch, a decision Geisel supported. But the singing would be assigned to a voice actor Jones had called in to perform several other background voices for the cartoon: Thurl Ravenscroft, a rangy 52-year-old with the sound Geisel wanted. “[Jones] handed me the song sheet, and we made it in about three takes,” recalled Ravenscroft. “We think it’s perfect,” said Geisel.

The only remaining point of contention was the story’s ending. In Geisel’s copy of the script, he had circled the Grinch’s great epiphany—“Maybe Christmas, he thought, doesn’t come from the store….”—and had written “slow delivery, as if dawn is breaking.” Geisel wanted the final moment to be deliberately paced—he had worked hard when writing the book in 1957 to make it as non-preachy as possible, and he didn’t want the cartoon going for an easy, saccharine, Technicolor Christmas ending. It was Noble who came up with an elegant solution, by having the Whos join hands and “create” a star as “a manifestation of their love and joy,” said Noble. “The star then moved up and joined with the Grinch, and he was transformed.” Perfect.

Geisel was convinced that he and Jones had something special on their hands. Jones, too, would always regard the Grinch with considerable pride. “How could anyone—how could I—not love the Grinch?” Both Jones and Geisel were right—and more than 50 years later, viewers still love the Grinch, who reliably descends on Whoville every December to steal Christmas—and, suitably transformed, just as reliably brings it back—a journey to Christmas redemption that began in Jacko, courtesy of the Bo-Boians in 1923.

Brian Jay Jones is the author of Becoming Dr. Seuss: Theodor Geisel and the Making of an American Imagination, from which this story is adapted. Published by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC © 2019.