Last April I sat on the Dartmouth Coach contemplating my next 60 days. The Dickey Center for International Understanding had given me the opportunity of a lifetime: To visit and tell the stories of students living abroad on Dartmouth-sponsored international internships. “We want to capture the unique ‘learning-while-doing’ experiences students have in the field,” Dickey acting director Christianne Wohlforth told me. “And we want to turn the telling of those stories into a professional development opportunity in itself.” (In January Daniel Benjamin, U.S. ambassador-at-large and coordinator for counterterrorism, will assume the directorship of the Dickey Center.)

Now in its 30th year, the Dickey Center has sent nearly 1,000 students around the world to engage in everything from working with U.S. embassies and development organizations to conducting scientific field research. Three years ago Dickey funded my own internship—in a maternity ward at St. Dominic’s Hospital in rural Ghana. The three months I spent there were some of the most grueling of my life. As I headed for the airport in Boston, I wondered if I was crazy to undertake another challenging international trip.

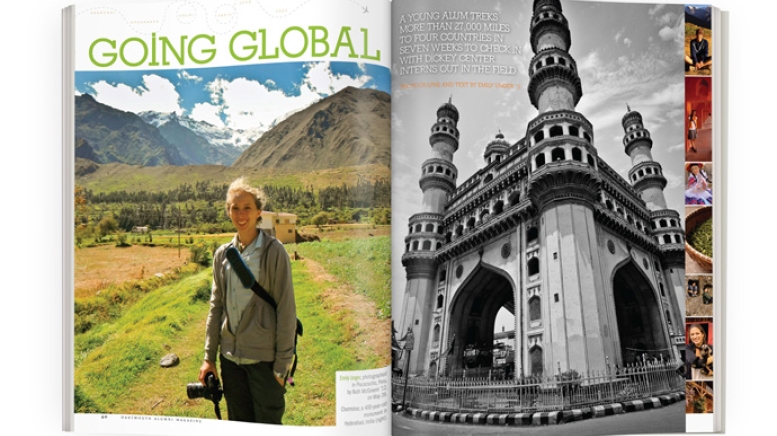

I also felt incredibly lucky to land the assignment. My backpack was stuffed with three cameras and 12 airline tickets that would take me on a 27,600-mile journey around the world from China to India to France to Peru.

As you’ll see, the miles were well spent.

Shanghai, China

After 15 hours on an American Airlines flight from Chicago, I boarded the Maglev train bound for the center of Shanghai. Watching the suburbs fly by at 430 kph was my introduction to China. What used to be an hour-and-a-half ride in a stuffy subway had become seven perfectly smooth minutes in a spotless train. I immediately realized how different this trip would be from my time in Ghana.

“Hospitals in China are really crowded,” Anna Bladey ’14 warned me as I followed her through the 12-story pediatric building of the Xinhua hospital. The number of people waiting for care was overwhelming.

Bladey was an intern with the Baobei Foundation, which arranges life-saving surgeries for orphans with birth defects. As we picked our way through hundreds of parents with screaming children, packed ourselves into overcrowded elevators and stepped over families camped in the hospital, I could see why Bladey’s work was so important. In a country where every child is an only child, orphans without advocates fail to get the healthcare they need.

Bladey had spent a term in Beijing on the Chinese foreign study program (FSP) in 2011. Seeking a more independent experience, she applied for funding from the Dickey Center for the internship she arranged at Baobei. When we met she was comfortable living in Shanghai and spoke reasonable Chinese, but she was grateful I was there to venture into places she would not have visited alone.

A few days later we boarded a bullet train for a lake in Hangzhou after reading in The Rough Guide to China that “no tour of China would be complete without appreciating the lake’s stunning natural beauty.” The water was tranquil, but we couldn’t see the other side of the lake because of pollution. Hordes of tourists shuffling around the water’s edge made me feel claustrophobic. Fearing the day was lost, we walked up a steep forested path and found a beautiful monastery filled with burning incense and men playing mahjong. We sat overlooking the lake and relished the quiet. Sometimes you get lucky, and the best experiences come from following a random path.

Hyderabad, India

Through the slits in their black burkas dozens of pairs of eyes fervently watched the headmaster of Lohia’s Little Angels School, in the heart of the city’s Muslim community, announce the top students in each class. The classroom was oppressively hot, and I was happy I wasn’t wearing a burka. As Reshma Lohia called out students’ names, each walked up excitedly to receive a certificate. I noticed most of the recipients were girls.

The school is one of dozens aimed at low-income families where the nonprofit Vital Opportunities In Creative Empowerment (VOICE), started by Averil Spencer ’10, lends assistance. The group aims to “improve the educational and employment opportunities for girls,” explained Spencer back in her Hyderabad apartment. “Parents want to protect and provide for their daughters, and the main way they can do that is to marry them into a financially secure family. We had girls who were 13 years old dropping out of school and getting married.” By teaching girls English, exposing them to career opportunities and helping them build self-esteem, VOICE helps them make the transition from childhood to womanhood in a society where women often lead restricted lives. Spencer said having the power to decide their own futures is essential to their safety and happiness.

She noted the challenges of living in India. “Suddenly I had to worry about what I wore, was I covered up enough, because if I wasn’t I’d be groped while I was in public places.” Spencer wasn’t going through this alone. Kashay Sanders ’11 was also working for VOICE and would be spending the next year in Hyderabad as well. As women’s and gender studies majors the two were living through what they had studied. The issues they faced as women in India were more challenging than they had expected.

I remembered how in Ghana men’s loud catcalls and groping followed me down every street. This behavior unnerved me, and it restricted what I could do and where I could go. Ironically, I envied the Muslim women wearing burkas. What the West views as an incredibly restrictive garment would have given me far more freedom. Some of the American volunteers in Hyderabad wore burkas to escape harassment.

Delhi, India

My first morning here I sat in a high-backed velvet armchair in the air-conditioned lobby of my hotel (the only time I didn’t stay in a hostel during the trip), utterly overwhelmed by the chaos flowing by the glass windows that shielded me from 110-degree heat. The bustling streets of the Paharganj district of Old Delhi were causing me some anxiety. The streets were only a car-width wide, yet cars moved in both directions along with dump trucks, farm tractors, motorcycles, auto-rickshaws, rickety bicycles piled high with everything imaginable, sacred cows, wild dogs and even camels, as well as an endless stream of people. Finally I worked up the nerve to wade in.

That evening I met with Sarah Alexander ’14 on the roof of her host family’s house. We looked out on a sea of multicolored cement houses, taking in the shrieks from a nearby cricket game, endless car honks and the constant roar of airplanes. Alexander said when she first arrived she thought Delhi was chaotic, but now she described it as “coexistence.” She told me to close my eyes and “imagine a jar full of rocks. Some are as small as grains of sand while others are as large as quarters. When traffic is flowing it’s like the jar is being violently shaken, but when traffic comes to a rest and the jar is set down, all the rocks fit together perfectly, leaving no empty space unused. This is Delhi.”

Alexander had traveled to India as a child and had longed to return. She decided to spend two months at the Center for Science and the Environment in the outskirts of Delhi. But this second trip was turning out to be quite different from the first. Alexander, an environmental studies major from Atlanta, lived in a residential area not featured on any tourist itinerary. She didn’t feel safe leaving the apartment alone at night, which made for a difficult social life. The oppressive heat, bucket showers and loneliness were beginning to wear on her. Alexander, just as I had been in Ghana, was frustrated with herself for not being happy.

In a different part of the city, three alums living together near lots of parks and restaurants were having a markedly different experience. They had air conditioning, a shower, a kitchen and fulfilling social lives and friend networks. I described Alexander’s predicament to them. “It’s definitely important to experience what Sarah’s going through,” Katharina Eidmann ’10 told me. “But it isn’t sustainable. We’ve all done our time like that, but to live here for years you have to make it more like home.” Eidmann also said finding a community was essential to happiness; you can live through anything if you have friends by your side.

Paris

On a memorable night in Paris I sat in a tiny creperie with a bright blue façade and a cheerful yellow light that kept the nighttime chill out. I was with Dickey intern Jina Choi ’13 and the friends she had made while interning at the U.S. embassy in Paris. Choi sat conversing easily in French with a man behind the counter who was pouring thin batter onto smoking griddles and skillfully flipping and folding paper-thin crêpes. They discussed the recent presidential election, French food and American politics. A double major in French and psychology who is from Nevada, Choi had gone on the French FSP the year before and fallen in love with Paris. Visiting France with other students had been a wonderful introduction to the city, but she knew there was more to discover in Paris on her own. Working with the U.S. ambassador and doing outreach in local neighborhoods on behalf of the U.S. government was a way to see if her dream of working in the Foreign Service was worth pursuing.

Earlier in the day I had followed the French FSP group led by professor David LaGuardia out of an ancient cathedral in Paris and down a narrow street lined with pastel buildings housing bakeries, crepe shops, fruit stands, cheese stores and other establishments dedicated to gastronomic perfection. It was heaven on earth.

After the bustling streets of India, Paris felt positively sleepy. I trailed the group, taking photos and enjoying the peace, looking forward to a week here.

Although the FSP students take classes, much of their learning occurs outside the classroom. “If we’re learning about the history of Notre Dame, we can go there and actually tour the church rather than study photos,” said Gillian Britton ’14. “Instead of reading about French politics, we get to be in Paris for a presidential election.”

Near Lyon, France

A day after taking the train here from Paris, I found myself at a farm feeding baby goats, learning about cheese making and sampling the finished product. I realized it was the smallest place I’d visited so far. Having grown up surrounded by farms in Vermont, this felt far more like home. I was on a two-day tour of the Auvergne region of France with the French language study abroad program.

A few days later I sat in the dining room of a French host family listening to English major Nancy Seem ’14 tell them in French about her experience in Auvergne. The table was set simply but the room, with its high ceilings and huge windows letting in the last rays of the setting sun, was lavishly decorated. As darkness crept in lights were turned on and we were fed course after course of home-cooked food. Our hosts poured me a glass of wine and told me I couldn’t eat bread and cheese without it. As I listened to Seem easily converse in French, I remembered her saying that when she first arrived she could barely understand her host family. Now, less than two months later, she could describe her day in detail.

Peru

Below me stretched the Sacred Valley of Peru, carved out by the roaring Urubamba River. The bottom of the valley featured a patchwork quilt of green fields and villages. Fortress-like Incan ruins were scattered among the rocky hills that erupted steeply out of the fertile land. Beyond the desolate foothills towered the snowy Andes framed against the crystal clear blue sky. I stood on the edge of a rock irrigation pool that was built into a steep hillside above the valley. I took a quick dip in the spring-fed pool. My bare feet relished the lack of shoes.

Later I jogged down a steep trail with my running companion, Sam Streeter ’13, and wound my way through the narrow cobble-stoned streets to our host family’s home for breakfast. Streeter, a biomedical engineering major from Wyoming, was volunteering for Sacred Valley Health (SVH), a small nongovernmental organization working to improve the health of the valley’s rural inhabitants. Another volunteer, Ruth McGovern ’12, was also working with SVH for the spring term. Before I arrived Streeter had described his host mother, Tina, as one of the nicest people he’d ever met. She greeted me with a warm hug. Streeter was clearly beloved—he washed his dishes and did his own laundry, rare for a man in Ollantaytambo. Tina’s sumptuous cooking kept us well fed after long days of work and exploring the mountains. Within only a few days I felt incredibly comfortable with this wonderful family.

During my 10 days there I got to see aspects of Streeter and McGovern’s work. I hit the ground running my first day at SVH because they were hosting a free clinic staffed by visiting American nurses. Because I spoke Spanish I was immediately plugged into the system. Most of the patients spoke only Quechua, so at each table sat a nurse, an English-to-Spanish translator and a Spanish-to-Quechua translator. It took awhile to communicate, but I learned a lot of medical Spanish. Beyond translating for American nurses at mobile clinics in Ollantaytambo and Socma, I visited community health workers in Piscacucho. We were kept busy dawn till dusk.

On Day Six the Peruvian festival Choquekilka began at dawn with fireworks. What followed were four days that fused loose Pentecostal beliefs with strong Incan traditions. Everywhere people in intricately sewn, colorful costumes and masks were dancing to live music. Tina took us to feasts where we were served qui, also known as guinea pig. My piece still had a claw that curled off the edge of the plate; it tasted a bit like greasy chicken. Because Streeter, McGovern and I were staying with host families we got to visit events that foreigners typically don’t see. I will never forget dancing with Streeter’s host family under the stars late into the night.

My week in Ollantaytambo was the most memorable of my trip. The meaningful and interesting work, the breathtaking scenery, the welcoming host families, the fascinating culture and the Peruvian and volunteer communities made this a great place to live and work. When I stood on the edge of the irrigation pool looking out at the Sacred Valley below me, I knew I could be happy living abroad in the right place. I realized that the success of an experience abroad relies on a few factors: work that feels meaningful and keeps you busy, and a social network to rely on. There also needs to be an outlet for fun, whether it’s cultural events in a city or hiking in the mountains. The students and alums I visited said their experiences have been incredibly challenging, but all agree that the positive aspects outweigh the struggles. I think there’s something to be said for making sure you’re happy while abroad. If you’re enjoying yourself, instead of wanting to shut out everything unfamiliar, you’ll want to see and do as much as possible.

Hanover, New Hampshire

Before I knew it I was back at Dartmouth sitting on the Green, sweltering in a cap and gown, eagerly waiting for my name to be called. (I’d taken extra time off to direct DOC first-year trips in 2011.) I realized that I was not nervous or sad. It seemed as if most of my classmates were entering this next chapter in their lives fearful of a looming emptiness. But after spending two months with students and alums who were still connected to one another, I knew what lay ahead: an even bigger community spread out across the globe that was ready to welcome all of us.

Emily Unger, a double major in biology and anthropology modified with global health, plans to take two years to gain work experience in public health before attending medical school. Unger’s blog from her trip can be found at emilygoesaroundtheworld.wordpress.com.