Leafing through the impressive resume of Craig B. Thompson, one might assume he was one of those kids who arrived in Hanover with a fully mapped career plan. In fact, it was happenstance that led him to Dartmouth, a bad choice of major that made him realize his true interests, and adaptive skills honed as a frequently uprooted “military brat” that helped him wring the most out of opportunities that came his way.

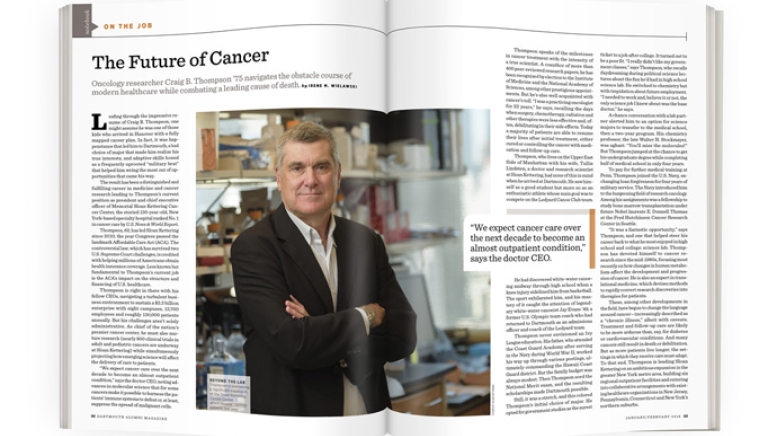

The result has been a distinguished and fulfilling career in medicine and cancer research leading to Thompson’s current position as president and chief executive officer of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the storied 130-year-old, New York-based specialty hospital ranked No. 1 in cancer care by U.S. News & World Report.

Thompson, 62, has led Sloan Kettering since 2010, the year Congress passed the landmark Affordable Care Act (ACA). The controversial law, which has survived two U.S. Supreme Court challenges, is credited with helping millions of Americans obtain health insurance coverage. Less known but fundamental to Thompson’s current job is the ACA’s impact on the structure and financing of U.S. healthcare.

Thompson is right in there with his fellow CEOs, navigating a turbulent business environment to sustain a $3.3 billion enterprise with eight campuses, 13,700 employees and roughly 130,000 patients annually. But his challenges aren’t solely administrative. As chief of the nation’s premier cancer center, he must also nurture research (nearly 800 clinical trials in adult and pediatric cancers are underway at Sloan Kettering) while simultaneously projecting how emerging science will affect the delivery of care to patients.

“We expect cancer care over the next decade to become an almost outpatient condition,” says the doctor CEO, noting advances in molecular science that for some cancers make it possible to harness the patients’ immune systems to defeat or, at least, suppress the spread of malignant cells.

Thompson speaks of the milestones in cancer treatment with the intensity of a true scientist. A coauthor of more than 400 peer-reviewed research papers, he has been recognized by election to the Institute of Medicine and the National Academy of Sciences, among other prestigious appointments. But he’s also well acquainted with cancer’s toll. “I was a practicing oncologist for 22 years,” he says, recalling the days when surgery, chemotherapy, radiation and other therapies were less effective and, often, debilitating in their side effects. Today a majority of patients are able to resume their lives after initial treatment, either cured or controlling the cancer with medication and follow-up care.

Thompson, who lives on the Upper East Side of Manhattan with his wife, Tullia Lindsten, a doctor and research scientist at Sloan Kettering, had none of this in mind when he arrived at Dartmouth. He saw himself as a good student but more so as an enthusiastic athlete whose main goal was to compete on the Ledyard Canoe Club team.

He had discovered white-water canoeing midway through high school when a knee injury sidelined him from basketball. The sport exhilarated him, and his mastery of it caught the attention of legendary white-water canoeist Jay Evans ’49, a former U.S. Olympic team coach who had returned to Dartmouth as an admissions officer and coach of the Ledyard team.

Thompson never envisioned an Ivy League education. His father, who attended the Coast Guard Academy after serving in the Navy during World War II, worked his way up through various postings, ultimately commanding the Hawaii Coast Guard district. But the family budget was always modest. Then Thompson aced the National Merit exam, and the resulting scholarships made Dartmouth possible.

Still, it was a stretch, and this colored Thompson’s initial choice of major. He opted for government studies as the surest ticket to a job after college. It turned out to be a poor fit. “I really didn’t like my government classes,” says Thompson, who recalls daydreaming during political science lectures about the fun he’d had in high school science lab. He switched to chemistry but with trepidation about future employment. “I needed to work and, believe it or not, the only science job I knew about was the base doctor,” he says.

A chance conversation with a lab partner alerted him to an option for science majors to transfer to the medical school, then a two-year program. His chemistry professor, the late Walter H. Stockmayer, was aghast: “You’ll miss the molecules!” But Thompson jumped at the chance to get his undergraduate degree while completing half of medical school in only four years.

To pay for further medical training at Penn, Thompson joined the U.S. Navy, exchanging loan forgiveness for four years of military service. The Navy introduced him to the burgeoning field of research oncology. Among his assignments was a fellowship to study bone marrow transplantation under future Nobel laureate E. Donnell Thomas at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

“It was a fantastic opportunity,” says Thompson, and one that helped steer his career back to what he most enjoyed in high school and college: science lab. Thompson has devoted himself to cancer research since the mid-1980s, focusing most recently on how changes in human metabolism affect the development and progression of cancer. He is also an expert in translational medicine, which devises methods to rapidly convert research discoveries into therapies for patients.

These, among other developments in the field, have begun to change the language around cancer—increasingly described as a “chronic illness,” albeit with caveats. Treatment and follow-up care are likely to be more arduous than, say, for diabetes or cardiovascular conditions. And many cancers still result in death or debilitation. But as more patients live longer, the settings in which they receive care must adapt. To that end, Thompson is leading Sloan Kettering on an ambitious expansion in the greater New York metro area, building six regional outpatient facilities and entering into collaborative arrangements with existing healthcare organizations in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut and New York’s northern suburbs.

The new facilities incorporate the changing science and outlook for patients, as well as cost-saving incentives in ACA to get patients out of the hospital as quickly as possible. The outpatient centers are located for easy access and designed for efficient use by patients fitting treatment into the rest of their lives. Intravenous chemotherapy, for example, is administered in lounge chairs equipped with computer screens and wi-fi so patients can stay in touch with the office or catch up on email. Options include Skype, video games and music.

From a research standpoint, these satellites of the mothership—Sloan Kettering’s Memorial Hospital in midtown Manhattan—greatly extend the reach of scientists seeking to enroll patients in clinical trials. The need for research participants grows with each new variant of cancer identified at the molecular level.

“In 2010 we had 24,000 patients come to Sloan Kettering with primary cancer,” notes Thompson. “In an era of personalized medicine, we need access to 50,000 patients because it takes a larger number of patients in these subdivided cancers for each trial to reach a valid conclusion.”

The ACA also potentially helps research by expanding health insurance coverage, thereby giving more people access to cancer treatments, including those still under study, according to Thompson.

It’s too early to say whether Sloan Kettering’s ambitious investment in decentralization coupled with broader insurance coverage will yield what Thompson envisions. The cancer center’s most recent outpatient facility opened only last year in Westchester County, New York. As with everything else in the rapidly transforming U.S. healthcare system, the cost-benefit ratio of these reconfigurations continues to be the wild card in long-range projections.

Rather than being daunted by such uncertainties, Thompson seems energized by them. Indeed, he speaks of the many variables in play—evolving science, the ACA’s structural and performance mandates, patient needs and preferences—with the buoyant optimism of one who has seen well-deployed science save lives and improve outcomes for people with cancer. He is determined to take these accomplishments as far as he can. “No one would be happier at this institution than me to put ourselves out of business,” he says.

Irene M. Wielawski, an independent healthcare journalist, lives in Pound Ridge, New York.