Since high school David Dingman dreamed of building his own airplane. The basement of his family home in Michigan was plastered with posters of aircraft, and he filled notebooks with sketches and drawings. He soloed at age 16 by hand-propping a tail-dragger that had no electrical system, no radio and only three instruments. “On my first cross-country trip I navigated by looking down and following the roads and rail tracks,” Dingman says.

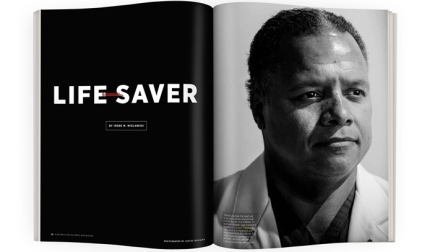

Nearly half a century later, in 2007 at age 71, he finally set out to build an aerobatic plane from scratch. He had sewn up a career as a mountaineer, reconstructive surgeon and medical director of the charity Interplast. He viewed retirement as an opportunity to do the hiking, climbing, skiing and flying he had postponed.

But which design? He had collected and studied planes through the years, and would simply have to borrow ideas and design features from several of them.

“Wood and steel are nice to work with because their engineering was figured out 70 years ago,” Dingman says. To connect the chrome-moly tubing that formed the fuselage, he taught himself to weld. In a shop in Michigan he fabricated the wing surface from thin pieces of birch plywood and a layer of carbon fiber—then tied the wing to the top of his van and negotiated it through a snowstorm to his home in the Sawtooths of Idaho. To cut and shape sheet metal for the body, he decamped to a workshop owned by the guy who installed the ventilation system in his home.

One of Dingman’s earlier, ambitious undertakings converged with flying when he was snagged for America’s first expedition to Mount Everest in 1963, along with Barry Corbet ’58, Barry Prather ’61, Barry Bishop ’53 and Jake Breitenbach ’57, who was lost there. The expedition really began, he recalled, when they boarded a rickety DC-3 in Calcutta to fly to Kathmandu. “The engines were leaking oil,” he says, “so I knew it was alive and functioning.” At cruising altitude, the co-pilot offered the young climbing doctor his seat in the cockpit, where Dingman took in a 300-mile-wide panorama of the Himalaya, from Annapurna to Kanchenjunga.

Following their success on Everest, Dingman and some of his Dartmouth teammates were selected by the CIA for a clandestine mission to the Indian Himalaya. They were flown into a remote airstrip on a Helio Courier and assigned to carry a nuclear-powered surveillance device to the top of 25,645-foot Nanda Devi. The device was lost en route—perhaps swept away in a landslide—so the team spent weeks choppering around the mountain in an H-43B, perched in the open back door, legs hanging out, searching for it with a Geiger counter. Flying turned out to be a sensational way to spend time in the mountains.

Two years shy of the 50th anniversary of the Everest expedition, Dingman rolled a single-seater, experimental aircraft dubbed the Dingbat out of his garage and went aloft. “It’s like seeing your firstborn—and realizing with relief that all the parts are there and working,” he says.

After building an airplane, what could be better than to build another one? “I love innovation and am addicted to approaching challenges in unique ways,” says Dingman. “As with some of my medical work, I like to get something up and running, then hand it over. Soon afterward, I get the bug to develop something new. Basically, I’ve failed at retirement.”

He’s now welding the fuselage of another aircraft—a high-wing bush plane with balloon tires and a single seat. (Insurance premiums are lower when you don’t have passengers, and you can build a lighter aircraft.) This tiny but sturdier plane is another hybrid, and will zip along at 150 m.p.h., yet land within a distance of 300 feet.

“Everything in aviation is evolutionary and a compromise,” Dingman says. “You can have high speed or a short takeoff and landing—or stability or maneuverability. It’s hard to have both.”

The pilot looks forward to exploring Idaho’s Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness, a popular destination for backcountry flying. At least 60 primitive airstrips were developed there in the 1920s and 1930s by pioneer bush pilots to protect their mining claims and supply their camps. Since then, the strips, often conveniently located along fly-fishing streams, have been maintained by the U.S. Forest Service for fire control. “There’s a collegial group of backcountry pilots who come from all over the United States, and they compete to see who can land on the gnarliest strip,” Dingman says.

Medical research suggests that cognitive tasks keep the brain sharp and help ward off dementia. “Constructing an airplane demands constant problem solving,” Dingman says, sipping from a bottomless cup of tea. “I get sleepy and bored when reading—but not when working in my shop. I have to force myself to stop or I’d work all night. The happiest guys I know are in workshops, building something.”

As the high-wing bush plane approaches completion, Dingman takes the low-wing aerobatic Dingbat out a few times a week to loosen it up with some loops and rolls over the Sawtooths. He does this within sight of the state’s fifth highest peak, Mount Breitenbach—renamed for his Dartmouth classmate Jake.

Broughton Coburn is the author of The Vast Unknown: America’s First Ascent of Everest. He wrote about Barry Corbet ’58 in the July/August 2013 issue of DAM.