On prime-time television if a young woman dares to go public with accusations of sexual misconduct against a prominent political figure, that’s the cue for Olivia Pope.

As the main character in the highly rated political thriller Scandal—created by Shonda Rhimes ’91—the glamorous D.C. crisis manager taps into a team of investigators and a network of powerful allies that include White House insiders and shadowy figures from secretive government agencies. In one episode, she shows up out of nowhere, takes a seat on a park bench next to an accuser and imparts some friendly advice about the downsides of taking on the president: “Amanda, it would be a mistake for you to think there will be no consequences for you telling lies about the president. I’m only here to warn you because you should know what could happen.

“It could become hard for you to find employment,” she warns. “Your face would be everywhere. People would associate you with a sex scandal. All kinds of information about you would easily become available to the press. You’ve had 22 sexual partners that we know of. Also, your mother’s mental illness and hospitalization after her psychotic break….She runs a daycare now, right?”

The young accuser melts into a puddle of tears. The threat diffused, Pope picks up her cell phone and delivers her catch phrase to the client: “It’s handled.”

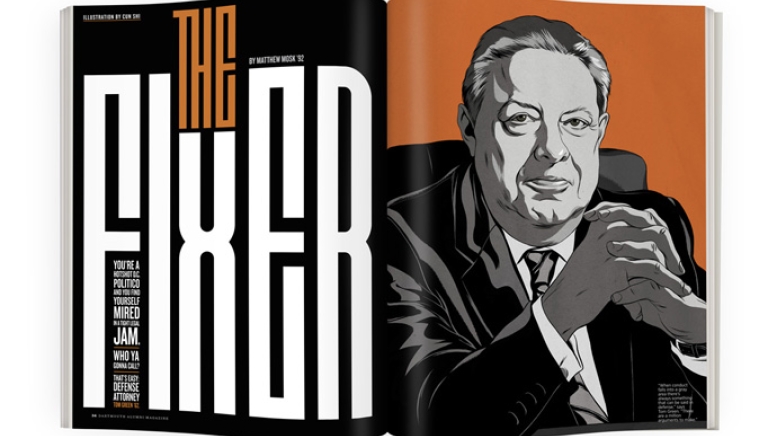

When real Washington scandals envelop powerful political figures, the fast-talking, glamorous fixer who can dig up dirt and bury problems is more myth than reality. As investigations start churning and tawdry accusations become grist for serious criminal charges, that’s the cue for a husky and decidedly unglamorous 75-year-old criminal defense attorney named Tom Green.

An under-the-radar veteran of the ultimate political scandal—Watergate—Green has helped secure acquittals and strike lenient deals for a parade of U.S. congressmen, spies, dignitaries and insiders stuck in potentially career-ending vortexes. He is unlikely to ominously threaten an accuser or dig into his or her sexual past, but he does concede he has used a range of tactics to intimidate prosecutors, cajole judges, corral the news media and win over juries. No one-size-fits-all solution will do. “It’s like being a chameleon,” he says. “You don the colors you need.”

Almost all of Green’s clients have avoided jail. At age 33, in 1974, he took the lead on the case of Robert C. Mardian, the one-time attorney for President Richard Nixon’s Committee to Re-Elect the President. Mardian’s initial conviction on conspiracy-to-obstruct-justice charges was overturned on appeal. When, in 1995, Sen. Dave Durenberger (R-MN) was accused of funneling campaign money into his personal accounts, he was fined $1,000 and given one year of probation. When Sen. Donald Riegle Jr. (D-MI) was accused in 1989 of helping the head of a savings and loan association skirt regulation in exchange for contributions as part of the Keating Five, a two-year U.S. Senate investigation found he had not violated any rules. When a group of businessmen was accused of giving money and favors to Democratic Maryland Gov. Marvin Mandel in 1975, Green’s client was found guilty along with the rest of them, but Green successfully appealed the verdict. And when the Pentagon’s Air Force Gen. Richard Secord was implicated in the Iran-Contra scandal in the late 1980s, Green kept him out of a cell. Deeply involved in the scheme to secretly arm paramilitary Nicaraguan rebels by using proceeds of illegal arms sales to Iran, Secord pleaded guilty to lying to Congress and received two years’ probation.

Green’s reputation for unwinding political knots and keeping clients breathing fresh air may explain why, last year, he received a call from a colleague of former House Speaker Dennis Hastert (R-IL). A retired Illinois congressman with a genial manner, Hastert rose to power in the 1990s and led the U.S. House of Representatives like an orchestra conductor for eight years. He appeared to be coasting into a tranquil retirement when news broke last May that he had been indicted. The charges were for alleged financial misdeeds, but lurking behind the banal accusations of illegally structured payments were far more sordid allegations. Hastert had made the improper payments, federal sources revealed to the media, to keep secret the claims that decades earlier he had sexually abused boys while serving as their high school wrestling coach in Yorkville, Illinois. In a matter of days, Hastert’s image plummeted. It would take more than a few punchy lines or pointed threats from a fabled political fixer to handle these allegations.

Brilliant June sunshine drenched the majestic pines surrounding the Bema when a young Tom Green stood up in a Native American costume to deliver the Sachem Oration to the class of 1962. Having composed his remarks in keeping with the history of the lighthearted lecture, Green opened with a familiar, if cheap, Sachem laugh line, telling his class he had trouble finding the sacred campus gathering spot: “It’s a good thing my donkey knew how to get here,” he dead-panned. “Hey fella, would you mind holding my ass for a while, while I give my talk?”

Green arrived in Hanover from Minnesota with an eye on freshman football. He still jokes about how long it took him to realize that the sideline cheers of “Go Green” were never intended for him. On the field he was unremarkable, but the broadcast booth was a different story. His deep baritone, quick wit and gift of gab quickly made him the popular voice of Dartmouth football and hockey on WDCR. One close friend, George Beller ’62, says it was that ease with oratory that eventually landed Green the Sachem gig—a rollicking talk that kept his classmates rolling. “The deans have been on a rampage lately,” Green had said. “They’ve outlawed water fights on campus, stick ball at Psi U and dogs from doing it on campus. About the only thing left to do is form gangs!”

As he prepared to graduate Green contemplated a career as a sportscaster. “At that time I probably mentioned it to my father and mother and received some different suggestions,” he says with a laugh.

“My first objective is to keep you out of jail, keep you breathing fresh air. That’s where I devote my energy.”

A more practical impulse drew Green to Yale Law School, a tenure that concluded with a telegram from the draft board, calling him to serve in Vietnam. Following a Dartmouth ROTC tradition, he joined the artillery. Secord remembers selecting Green as his attorney for the Iran-Contra matter after learning that the young lawyer had turned down the safety of the JAG Corps for the Vietnamese jungle and a Howitzer: “I said to him, ‘You were a Yale Law School graduate in the artillery? Tom, how did this happen?’ He said, ‘I don’t know, General. It must have been the Hemingway in me.’ ”

When Green returned from war, he came to the nation’s capital in search of a job as a prosecutor. He landed an interview with David G. Bress, the U.S. attorney, but after a promising, hour-long interview, Bress turned him down, telling Green he lacked the required clerkship or minimum two years in private practice. Green pushed back. “I told him I had just been fighting a war for my country while all these other guys with their bad backs and their bum knees had been here,” he recalls. “I said, ‘I need a job. I’m broke. I have to go to work.’ ”

Green prevailed. He had not only talked his way into the position, but when Bress later broke away to form his own firm, he hired Green to join him. Green was at Bress’ side in 1972, when Mardian, the former Nixon aide involved in the coverup, called on the firm to mount his defense in the Watergate prosecution. During trial preparation Green walked daily to the basement of the Washington, D.C., federal courthouse, where a bank of reel-to-reel players was set up for attorneys to listen to the now-infamous secret Oval Office recordings of Nixon and his aides. “Every day I would go home thinking, this can’t get any more incredible,” Green recalls. “This is the president of the United States saying, ‘We got to get the money to pay these guys to shut them up.’ You had to hang onto your chair or you would fall out.”

When Bress suddenly fell gravely ill, the judge handed Mardian’s case to Green. Mardian was convicted on one count of conspiracy to hinder the investigation, as were other top aides John Mitchell, Robert Haldeman and John Ehrlichman. But on appeal, Mardian’s verdict was overturned. He was the only one of the four to avoid jail time. Green had his first taste of white-hot Washington scandal—and victory. He was hooked.

Damage control was Green’s priority when the Iran-Contra scandal broke. It wasn’t easy. In 1984 Secord undertook a shadowy venture to help finance a secret effort to assist the Nicaraguan Contras with arms sales to Iran. Two years later, when he sought Green’s help with the legal fallout, Green remembered Watergate. “This was another one that could have brought down a president,” Green says.

Green first sought to head off the scandal by walking into the U.S. Justice Department in November 1986 to see if the government would consider immunity for Secord and alleged mastermind Lt. Col. Oliver North in exchange for their cooperation. He got his answer later that afternoon, when he heard a report on the radio that President Ronald Reagan had informed North he was “relieved of his duties” as a member of the National Security Council staff. As the heat of the controversy grew, in spring of 1987, an increasingly angry Congress issued more challenges. Green said his client approached the investigation against him the same way he approached everything: “Hear no evil, fear no evil.” Green sat beside Secord in May as the general came under harsh examination by a key senator during four days of testimony. Green was opposed to Secord testifying, but says Secord relished the fight. Secord recalled that the first question to him, delivered “in a sneering tone,” was, “General, have you ever read the Constitution?”

“It was such a surprise to me. I said, ‘Yes, Senator, I have read the Constitution and even had the chance to fight for it a couple times.’ ” As the questioning continued, Secord says he became so steamed that he was preparing to unload on his interrogator by publicly raising a nasty rumor circulating about the senator. Green stepped in. “Tom was reading my mind,” says Secord of Green’s lawyering. “I swear to God. I was going to raise the rumor, so Tom interrupted me and shouted out, ‘Mister Chairman, we need 10!’ They adjourned.”

Secord says Green and the chairman disappeared into a private room. When they finally emerged, Green assured Secord the questioning would come to a brisk conclusion. “He knew exactly what steps to take,” says Secord. “My friends said he saved me from getting into the muck.” Green says he remembers trying to keep Secord from overstepping. “In the recesses I was beating him up pretty good to not be so adventuresome in his remarks,” Green says.

Green says he has always believed the initial burst of media attention in a scandal such as the one involving Hastert can mask a far more nuanced case. To expose these nuances requires a willingness to challenge the assumptions of the public and of government lawyers. “When you’re a white-collar defense lawyer, it’s not for the faint of heart,” he says. “You need to be prepared to push back on the government and sometimes push back very vigorously. It can make you unpopular in today’s world, but I can say quite comfortably that virtually every client I’ve ever had, whether they be from the world of politics or elected officials or even corporate executives, their conduct fell into a gray area. When conduct falls into a gray area there’s always something that can be said in defense, in mitigation, to convince the prosecutors that it’s a case not worthy of prosecution or that should be handled administratively. There are a million arguments to make.”

Green acknowledges the Hastert case was vexing. When he first began building a strategy, it was clear at least part of his plan would be to lean hard on the prosecutors for, he believed, leaking details of the sexual abuse allegations that lurked behind the financial charges. In private negotiations with the prosecutors, and then in open court last June, Green blasted the lawyers for exposing the accusations. “I made clear to government counsel my displeasure over the leaks that have filtered out to the media and have communicated my concern over the prejudice that those leaks are causing,” Green told the judge, according to court transcripts. “I mean, something has to be done to stop these leaks. They’re unconscionable and they have to stop.”

Challenging prosecutors did not provide Green with the leverage he needed to slow the investigation, so he changed tactics. With Hastert’s reputation already sullied, Green moved to minimize the jail time his client might face by building a case for his client’s remorse and declining health. When Hastert pleaded guilty last October to financial misconduct that could yield up to five years behind bars, Green set out to persuade the court to spare him as much time as possible. Ultimately, he says, his client’s freedom sits at the top of his priorities.

“I’m very blunt,” he says. “I tell [clients] that I can’t be a savior when it comes to your reputation. I can try to influence the amount of information that is publicly disclosed about this matter. I can try to talk to the press and, using just the force of reason, explain why they should not publish a particular story. But the reputation is a secondary objective. My first objective is to keep you out of jail, keep you breathing fresh air. That’s where I devote my energy.”

In April, as Hastert’s sentencing date loomed, achieving that goal seemed unlikely. Victims who said Hastert abused them during their school days began stepping forward with stories. One announced he wanted to speak about his sexual abuse in open court. Green realized his client was in trouble. “It was like a dike with a new hole every hour, and we ran out of fingers.”

In newspaper interviews and in a lengthy pre-sentencing report, Green repeated Hastert’s statements of remorse and regret. He spoke of Hastert’s lifetime dedication to public service and of his heartfelt effort to correct the wrongs of his past. “He is overwhelmed by the guilt he feels for his actions, for the harm he caused by his misconduct, and for disappointing those who have supported him for so long,” Green wrote of Hastert, 74, in an April sentencing memorandum. With the sentencing date imminent, Green began peppering the court with evidence of Hastert’s rapidly declining health—after surviving an almost-fatal blood infection last fall, the former congressman suffered a stroke that had confined him to a wheelchair. Green argued these factors would make his client ill suited to a long stretch behind bars.

But there would be no Hollywood ending for Green and his client. Just days before Rhimes and the cast of Scandal would tour the White House to promote their show, Hastert stood before Judge Thomas Durkin and expressed his shame. The judge was unmoved. “If I’m going to consider the good history and characteristics of the defendant, I must also consider the bad, which is that the defendant is a serial child molester,” said Durkin.

He then handed down Hastert’s sentence—15 months in prison—indicating Hastert would likely be placed in a medical referral center operated by the Bureau of Prisons. “I’ll agree with you, Mr. Green, that this is a tragic and sad case,” Durkin said.

It was not a typical outcome for Green. Still, if his past cases are any guide, this may not be the end to his lawyering in the case. Not every scandal can be solved with a well-placed threat or the intervention of a powerful ally—or with Olivia Pope uttering her catch phrase, “It’s handled.”

Matthew Mosk, an Emmy Award-winning investigative journalist for ABC News, lives in Annapolis, Maryland.