Kelsey Justis ’16, a first-generation student from Daytona Beach, Florida, never imagined he’d go to an elite college. At his inner-city high school, teachers didn’t expect most students to graduate, much less land in the Ivy League. Even his mother wasn’t eager for him to go to college. She struggled with financial and health problems and relied on her son’s help at home. Like the majority of first-generation college students, Justis comes from a low-income household. He excelled in high school and even took advanced science classes at local community colleges because he had placed out of the regular courses at his high school. He was lucky. Through the highly selective QuestBridge program, a national nonprofit that connects high-achieving, low-income students with top colleges, Justis received a scholarship to Dartmouth, a school he hadn’t considered.

Like many first-generation students who have beaten the odds to graduate from high school and gain acceptance to college, he faced a whole new world at Dartmouth. In his freshman year his dream almost fell apart. Justis found that even though he had been a top student in high school, he was at a disadvantage when competing with students from more privileged backgrounds. “My first quarter I withdrew from a class and got two B’s,” he says. “I kept trying classes that were too hard. Which was a big surprise because I got nothing but A’s throughout high school.” Justis considered dropping out, thinking he wasn’t suited for college. But he persisted. His hard work has him on track to graduate this spring with a major in physics, modified with computer science, and a minor in math.

Organizations such as QuestBridge help the College increase the socioeconomic diversity of the student body, which President Phil Hanlon ’77, in his Moving Dartmouth Forward plan, outlined as a key objective for the future. The number of first-generation students at Dartmouth is indeed increasing. In the past four years the number of first-gen students enrolled in the College has grown by a third. Dartmouth’s class of 2019 has the highest number since the admissions office began collecting the figure in 2004: 13.4 percent, or 149 students. This growth reflects a national trend. More first-generation students are being recruited and admitted to the Ivies and their peers than ever before.

Justis explains that he and other first-gen students face many obstacles on the way to academic success. At home, financial hardship pressures them to start earning money as soon possible. Underfunded, overcrowded public schools often prepare them insufficiently for college and, once there, students tend not to be aware of available resources. “I didn’t go to my first office hour until my sophomore year,” says Justis. “I didn’t know what the use of it was. I didn’t want to go to a prof and show that I was stupid!”

First-gen students can also miss networking opportunities and find themselves isolated because work and study leave little time to socialize. It can also be difficult to find common ground with more affluent students. Justis, whose father died when he was an infant and whose disabled mother lives on an income of less than $11,000 a year, felt uncomfortable hanging out with other students because he worried his hardships would put them off. “How do you sugarcoat that to sound like a nice, attractive personality, you know, someone other people want to hang around and not feel in the dumps about?” asks Justis. “You don’t want your life to depress other people.”

Juliet Morales ’18, a first-gen student from a farming town in eastern Connecticut, had never thought of herself as poor or underprivileged, but then she arrived in Hanover. It affected her self-image and confidence. “It made me feel isolated. People who are of higher socioeconomic status or who are legacies don’t even notice they’re saying or doing certain things that are insensitive,” she says. Morales recalls being mortified when a fellow student urged her to view online pictures of the student’s home. As the student pointed out her new pool house, Morales noticed the multimillion-dollar value of the property. “It was like she was rubbing it in,” Morales says.

Many students hesitate to discuss openly their first-generation status out of fear that they will quickly be dismissed as affirmative action beneficiaries. Legacies, on the other hand, speak with pride about their alumni relatives.

“They have a right to feel proud of that,” says Morales, who thinks that admitting legacies is just as much a form of affirmative action as recruiting disadvantaged students. (Both legacy and first-gen applicants receive special consideration in the admissions process.)

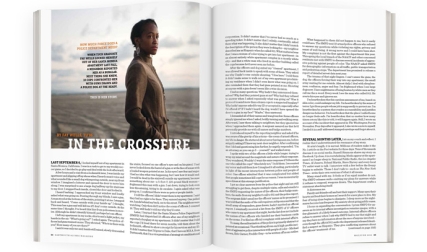

Like Justis, Morales has experienced situations in which other students flat-out dismissed her opinions because she acknowledged that she came from a working-class background. The social anxiety that Morales experienced as a freshman eventually triggered a panic attack that led to her admittance to Dick’s House, home to the College’s health services.

Another first-generation student, Micah Daniels ’18 from Utah, has struggled with stress. Daniels, whose family lives on the Navajo Reservation in Blanding, didn’t consider going to college until a high school counselor recognized her talent and encouraged her to reconsider. The counselor helped Daniels apply for MS Squared, a summer program at Phillips Academy that promotes math and science education for disadvantaged minority students.

About the time Daniels was accepted at Dartmouth her father lost his job due to medical problems, and as a freshman she found herself working two jobs so she could send money home to help her parents. “Sometimes I feel so overwhelmed that I just don’t even want to get out of bed,” she says. Daniels credits Dartmouth’s First Year Student Enrichment Program (FYSEP) with helping her through the most difficult times. “It’s the whole reason that I have the success that I have here,” she says.

FYSEP, a pre-orientation and yearlong mentorship program, was launched in 2009 as a student-led group and then funded by the dean of the College office with the goal of helping underprivileged first-gen students thrive at Dartmouth. “The focus is not whether or not our students graduate, but that they have every opportunity to thrive at Dartmouth,” says director Jay Davis ’90. According to the admissions office, Dartmouth’s six-year graduation rate for first-gen students is 93 percent, compared to a 24.9-percent nationally for first-generation students above the poverty line and 10.9 percent for those deemed low-income, as computed by the Pell Institute. Paradoxically, first-generation students are more likely to succeed at highly competitive elite schools than at large state schools, which offer fewer resources, such as FYSEP, to help them navigate college life.

“We’re most concerned about the quality of their experience while they’re here and how much they take advantage of the opportunities and how much the College meets their needs,” Davis says. “First-gen students often have little awareness that they are not alone in their struggle. FYSEP is a place where students can allow themselves to be vulnerable so they can see that struggle is normal.” FYSEP has limited resources and cannot accommodate all eligible students, but the program, which falls under the College’s student affairs budget, is growing, says Davis. (Student Affairs declined to provide FYSEP budget figures). Last year 80 students who were deemed most in need of support were invited to join.

Jordan Are’ ’15 from Houston, Texas, was among those invited during his freshman year. His parents always emphasized the importance of education and encouraged him to work hard to excel both academically and as an athlete. In his junior year in high school Are’ was recruited to play football. Coming from a predominantly black and Hispanic high school, he experienced some culture shock at Dartmouth.

“There was an adjustment period in terms of me being surrounded the majority of my life by people with whom I share a similar culture, traditions, behaviors and simple things such as language or whatnot,” says Are’. He also had to balance academic and athletic pressures. “FYSEP single-handedly instilled confidence in my ability,” says Are’, now an analyst with Morgan Stanley in New York City. “Seeing other first-generation college students with similar narratives, and a lot of things that they had been through and how they got to where they were today, resonated with my experiences.”

“FYSEP members aren’t scared to talk about subjects that others don’t want to touch,” says Cecilia Torres ’18, another participant. The daughter of a construction worker and a factory worker, Torres was born in Mexico City and immigrated with her family to Dallas when she was 5. Her parents used to tell her that she had to study hard and get an education so she could find a better job. Torres was indeed a top student at her predominantly black and Hispanic high school and was accepted with a scholarship to Dartmouth through the QuestBridge program. But once enrolled at the College, Torres found that her life experience was a taboo subject: “During orientation I remember people being really awkward when a subject was brought up that could be considered politically incorrect, such as racism or inequality of some sort,” says Torres. “Only in FYSEP were people willing to talk openly.”

Their sense of invisibility has inspired some first-gen students to launch initiatives that promote awareness of the socioeconomic divide at Dartmouth. “The norms that you encounter in an Ivy League school, where the majority of students come from wealthy backgrounds, can make you feel like you’re not part of the Dartmouth community in many ways,” says Hui Cheng ’16, the daughter of Chinese immigrants. With Emily Chan ’16, a co-director of Dartmouth Quest for Socioeconomic Engagement—a student-support group that initially started as a group for QuestBridge students—Cheng launched a Facebook page called Dartmouth Class Confessions, which facilitates an online conversation about difficult topics such as poverty and educational inequality at the College. The page profiles first-gen students and invites members of the Dartmouth community to anonymously share personal experiences.

The confessions reveal worries ranging from embarrassment about not having the funds to join friends for dinner at a restaurant and anxiety about student loans to shame about coming from a working class background and feeling guilty for indulging in pursuits that may not lead to financial security. One anonymous alumnus confessed to abusing drugs and alcohol to bury his shame at trying to conceal his own blue-collar background when he was a scholarship student at Dartmouth 50 years ago. “Be proud of your roots! You have accomplished so much more than those who were born with the silver spoon,” he wrote.

Similar projects have been launched at Columbia, University of Chicago and Northwestern. More recently Wellesley, Brown, Stanford, Pomona, Emory and Cornell have also started Class Confession pages. Students at Tulane cited the Dartmouth page as inspiration for the creation of their site.

“When you go through an elite institution like this, it’s easy to try to forget where you are,” says Ilenna Jones ’15, a co-director of Dartmouth Quest for Socioeconomic Engagement. “The American dream is all about forgetting or trying to push away your status as a poor person. It’s almost shameful, looked down on, valued less.” This is an attitude she wants to change.

Jones compares her own situation to the lives of her high school classmates who now work and take care of their families. “I’m here in my dorm,” she says, “which is a 10-minute walk away from my class, and all of my food is made for me. And, really, I think that I’m special, that I’m better than other people? What’s wrong with me?”

Juliet Morales, the student who experienced a panic attack during her freshman fall, is doing better. She sought counseling and realized that for her own mental health she had to seek out friends with whom she did not feel pressured to hide her background. She now feels happy at Dartmouth and hopes that one day she will be able to help her nephew become a legacy student. “He’s going to have those connections that I’ll help foster for him,” she says. “And knowing that I can help someone I love, that definitely helps me power through any rough time.”

Judith Hertog is a regular contributor to DAM. Lexi Krupp is a former DAM intern.