The 1970s were an electric decade for Dartmouth. With war protesters crowding Parkhurst Hall, dissent rising over the College’s use of Native American imagery and women enrolling for the first time, campus life reflected the charged climate of the nation. Yet as some were getting fired up, going toe-to-toe with the establishment, others, such as Massachusetts-born Garson Fields ’73, were out fighting real flames.

Just moments after arriving on campus, Fields decided to become a volunteer fireman. “I walked downtown just to get the lay of the land and there was a sandwich board out in front of the fire station,” he says. “I walked in and signed up.” At first Fields failed to realize he was joining a long line of Dartmouth men who had once served as firefighters.

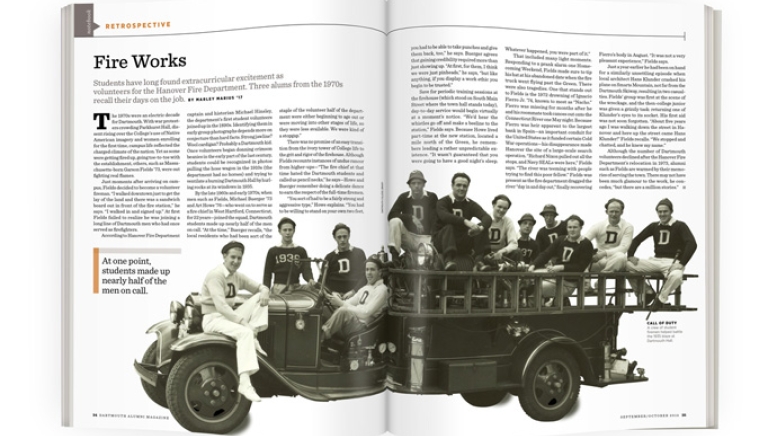

According to Hanover Fire Department captain and historian Michael Hinsley, the department’s first student volunteers joined up in the 1890s. Identifying them in early group photographs depends more on conjecture than hard facts. Strong jawline? Wool cardigan? Probably a Dartmouth kid. Once volunteers began donning crimson beanies in the early part of the last century, students could be recognized in photos pulling the hose wagon in the 1910s (the department had no horses) and trying to ventilate a burning Dartmouth Hall by hurling rocks at its windows in 1935.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, when men such as Fields, Michael Buerger ’73 and Art Howe ’76—who went on to serve as a fire chief in West Hartford, Connecticut, for 22 years—joined the squad, Dartmouth students made up nearly half of the men on call. “At the time,” Buerger recalls, “the local residents who had been sort of the staple of the volunteer half of the department were either beginning to age out or were moving into other stages of life, so they were less available. We were kind of a stopgap.”

There was no promise of an easy transition from the ivory tower of College life to the grit and rigor of the firehouse. Although Fields recounts instances of undue rancor from higher-ups—“The fire chief at that time hated the Dartmouth students and called us pencil necks,” he says—Howe and Buerger remember doing a delicate dance to earn the respect of the full-time firemen.

“You sort of had to be a fairly strong and aggressive type,” Howe explains. “You had to be willing to stand on your own two feet, you had to be able to take punches and give them back, too,” he says. Buerger agrees that gaining credibility required more than just showing up. “At first, for them, I think we were just pinheads,” he says, “but like anything, if you display a work ethic you begin to be trusted.”

Save for periodic training sessions at the firehouse (which stood on South Main Street where the town hall stands today), day-to-day service would begin virtually at a moment’s notice. “We’d hear the whistles go off and make a beeline to the station,” Fields says. Because Howe lived part-time at the new station, located a mile north of the Green, he remembers leading a rather unpredictable existence. “It wasn’t guaranteed that you were going to have a good night’s sleep. Whatever happened, you were part of it.”

That included many light moments. Responding to a prank alarm one Homecoming Weekend, Fields made sure to tip his hat at his abandoned date when the fire truck went flying past the Green. There were also tragedies. One that stands out to Fields is the 1972 drowning of Ignacio Fierro Jr. ’74, known to most as “Nacho.” Fierro was missing for months after he and his roommate took canoes out onto the Connecticut River one May night. Because Fierro was heir apparent to the largest bank in Spain—an important conduit for the United States as it funded certain Cold War operations—his disappearance made Hanover the site of a large-scale search operation. “Richard Nixon pulled out all the stops, and Navy SEALs were here,” Fields says. “The river was teeming with people trying to find this poor fellow.” Fields was present as the fire department dragged the river “day in and day out,” finally recovering Fierro’s body in August. “It was not a very pleasant experience,” Fields says.

Just a year earlier he had been on hand for a similarly unsettling episode when local architect Hans Klunder crashed his plane on Smarts Mountain, not far from the Dartmouth Skiway, resulting in two casualties. Fields’ group was first at the scene of the wreckage, and the then-college junior was given a grizzly task: returning one of Klunder’s eyes to its socket. His first aid was not soon forgotten. “About five years ago I was walking down the street in Hanover and here up the street came Hans Klunder!” Fields recalls. “We stopped and chatted, and he knew my name.”

Although the number of Dartmouth volunteers declined after the Hanover Fire Department’s relocation in 1973, alumni such as Fields are warmed by their memories of serving the town. There may not have been much glamour to the work, he concedes, “but there are a million stories.”