Click here to view illustrations from the field guide in the DAM archive

My father was a passionate golfer. Throughout my childhood he played on weekends, sometimes 36 holes in a day. When he retired in 1982, he played five days a week until he died in 1997. I’ve never cared much for the game myself, but lately I’ve been spending a lot of time at Hanover Country Club. Or, to be precise, in the rough between the seventh and 15th fairways.

I go there because of the pugnacious, robin-sized falcons known as merlins. And the merlins go there because of the crows. None of us play golf.

During the past 30 years merlins have extended their breeding range out of the boreal forests of Quebec and Labrador south into northern New England because of two decidedly related events. First, we’ve carved suburban parks and golf courses out of solid forests. Second, crows have found our land use practices much to their liking.

Merlins can swoop at 60 m.p.h., grab a hapless warbler or a swallow out of the air and then pluck and feed without breaking stroke, eddies of feathers trailing behind them. They are superb aerialists and pester bigger birds, such as hawks and crows, swooping and diving and chasing. All the while screaming, always screaming.

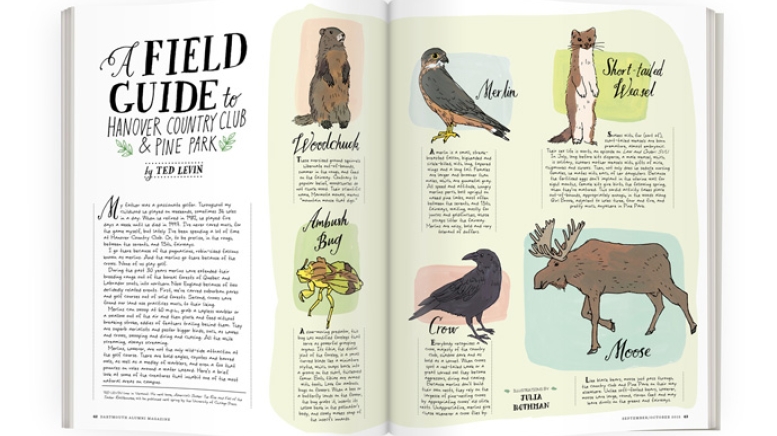

Merlins, however, are not the only wild-side attraction at the golf course. There are bald eagles, coyotes and barred owls, as well as a medley of warblers, and even a fox that pounces on voles around a water hazard. Here’s a brief look at some of the creatures that inhabit one of the most natural areas on campus.

Woodchuck

These oversized ground squirrels hibernate out-of-bounds, summer in the rough and feed on the fairway. Contrary to popular belief, woodchucks do not chuck wood. Their scientific name, Marmota monax, means “mountain mouse that digs.”

Ambush Bug

A slow-moving predator, this bug has modified forelegs that serve as powerful grasping organs. Its tibia, the distal joint of the foreleg, is a small curved blade like a miniature scythe, which snaps back into a groove on the short, thickened femur. Both tibiae are armed with teeth. Look for ambush bugs on flowers. When a bee or a butterfly lands on the flower, the bug grabs it, inserts its hollow beak in the pollinator’s body, and slowly makes soup of the insect’s innards.

Merlin

A merlin is a small, streak-breasted falcon, bigheaded and sickle-billed, with long, tapered wings and a long tail. Females are larger and browner than males, which are gunmetal gray. All speed and attitude, hungry merlins perch bolt upright on naked pine limbs, most often between the seventh and 15th fairways, waiting, mostly for juncos and goldfinches, whose scraps litter the fairway. Merlins are noisy, bold and very tolerant of duffers.

Crow

Everybody recognizes a crow, majesty of the country club, shadow dark and as bold as a hornet. When crows spot a red-tailed hawk or a great horned owl they become aggressors, diving and cawing. Because merlins don’t build their own nests, they rely on the largesse of pine-nesting crows by appropriating crows’ old stick nests. Unappreciative, merlins give chase whenever a crow flies by.

Short-tailed Weasel

Snakes with fur (sort of), short-tailed weasels are born premature, almost embryonic. Their sex life is worth an episode on Law and Order: SVU. In July, long before kits disperse, a male weasel, which is solitary, showers mother weasels with gifts of mice, chipmunks and shrews. Then, not only does he seduce nursing females, he mates with each of her daughters. Because the fertilized eggs don’t implant in the uterine wall for eight months, female kits give birth the following spring, when they’ve matured. This sordid activity takes place out-of-bounds, appropriately enough, in the woods along Girl Brook, adjacent to holes three, four and five, and pretty much anywhere in Pine Park.

Moose

Like black bears, moose just pass through the country club and Pine Park on their way elsewhere. Unlike soft-footed bears, however, moose have large, round, cloven feet and may leave divots on the greens and fairways.

Antlion

A bunker can be a fatal trap for ants of all kinds. Conical depressions in the loose sand belong to antlions (the larvae of the dobsonfly), which wait just below the surface, each one an ant’s personal prince of darkness. They’re about the size of your fingernail, with bulbous bodies and oversized, hollow, sickle-shaped mandibles. An ant that slips into a pit is pulled below the surface, its guts liquefied and then drained dry. Once an antlion is through feeding, all that’s left of its victim is a dried husk.

Red Fox

Foxes are the gymnasts of the canine world, airborne little dogs that float past the defenses of small mammals, particularly meadow voles. Once a fox pinpoints a vole by leaning into the sound, an ear cocked toward the ground, it leaps straight up into the air. At the height of the jump the red fox jackknifes and its front paws strike the ground first, pinning the vole beneath them. They can be seen in the morning and late afternoon, particularly in the rough and around the eighth-hole pond.

Garter & Milk Snake

A freshly shed garter snake is shiny green-black with a long yellow stripe. A milk snake may sound like a rattlesnake and look like a copperhead, but fear not. It’s as harmless as a short uphill putt. It lays seven or eight oblong eggs, often in a rotted log. Sporting an off-white base color, red-brown to brown blotched, with a cream-colored “Y” or “V” on the nape, a milk snake constricts and then eats small mammals, ground-nesting birds and other species of snakes.

Star-nosed Mole

Hairy-tailed moles prefer drier loam. Star-nosed moles prefer saturated earth. A star-nosed mole, which has 22 fleshy projections on its nose, looks as though an octopus grafted to its face. Both species are subterranean, nearly blind and have wide, forward-facing front paws with long claws. Their short, thick, front legs are rotated 90 degrees in the shoulder socket, which allows them to swim through the soil.

Black Bear

Black bears concentrate their activities in the woods, rooting for beetle grubs, ants and yellow jackets. More often than not they’re on their way to raid bird feeders along Occom Ridge and Rope Ferry Road or to visit Baker lawn, where one was once known to have passed time in a maple tree, studying activities on the Green.

Barred Owl

Famed for soft feathers, silent flight and the unerring ability to hear high-pitched sounds, barred owls nest in the woods, most often in tree cavities, from which they pounce on unsuspecting quarry, usually mouse, shrew or frog. In the late afternoon or on an overcast day listen for the barred owl’s doglike barks or maniacal caterwauling, reminiscent of the sound of someone muffing a three-foot putt. A barred owl’s more familiar call, however, is a string of hoots, high-pitched and hollow, that sound like, “Who cooks for you, who cooks for you all?”

Vole

This roly-poly hamster-like mouse has a hard-to-define breeding season. Any month of the year seems to work. If they survive long enough, eight to 10 litters a year with one to eight young per litter is the norm. At that rate, within just three years there would be enough meadow voles to stretch a vole-to-vole carpet across New Hampshire. Fortunately, everything from red foxes to milk snakes keeps them in check. Look for them along the edges of the fairways and in the thick grasses surrounding the eighth-hole water hazard.

Spring Peepers & Wood Frogs

Frog calling is all about mating. Males form the chorus. Females respond, selecting potential mates by the quality of their voices. Fertilization is external. During amplexus, the sexual embrace of frogs, the male (always the smaller of the two) climbs onto his mate’s back and grips her behind the forelegs to force out her eggs, which he then showers with sperm. Both wood frogs and spring peepers leave the woods and cross the fairways on the first warm, rainy night in April, heading to the eighth-hole water hazard, where they spawn. Wood frogs, which are 3 inches long and light to dark brown with a very dark mask, mate in a scrum, frog on frog on frog, kicking and squeezing. About an inch long, peepers are much more sedate. Although their breeding season extends into early July, it’s never a free-for-all, just a mind-numbing electronic ensemble. Females deposit eggs one at a time, here and there throughout the eighth-hole hazard.

Ted Levin lives in Vermont. His next book, America’s Snake: The Rise and Fall of the Timber Rattlesnake, will be published next spring by the University of Chicago Press.