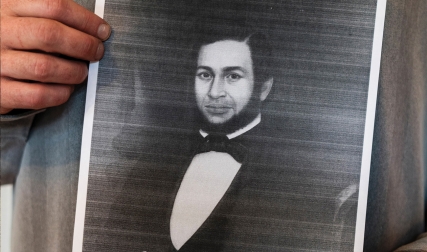

I ’ve never met Leon Burr Richardson, class of 1900, but I know him well. He was 5-foot-8, around 165 pounds. He was a “whole-hearted Republican” and professed “no particular belief.” He could trace his family back to Samuel Richardson, born 1610. I’ve held Leon’s birth certificate, his wife’s birth certificate, his passport, his mother’s will. I’ve paged through menus from his favorite restaurants. I’ve seen his family photographs. I’ve looked at pictures of him at 3 months old, at 6 months, at 4 years, at 8. I’ve seen his pay stubs, and I know when he got a raise. I’ve held the deed from Glenwood Cemetery, where he and his family are buried. They rest in Lot 9.

Joshua Lascell, assistant archivist for acquisitions and collections, assigned Richardson’s files for my first processing project as a Special Collections fellow. In the archive world, “processing” refers to the surveying, reorganizing, and describing of archival materials. As I sort through the packet, Josh tells me that I should replace metal paper clips with nondamaging plastic ones and keep an eye out for dry mold and squirrel urine (a genuine problem, he confirms).

Josh advises me to skim—not read—the materials. There are too many files and no real reason to know too much about Leon Burr Richardson, or L.B., as his friends called him.

Here’s what a skim reveals:

Richardson grew up in Lebanon, New Hampshire, and after he graduated from Dartmouth, he taught as a professor in the chemistry department for 46 years.

He wrote a few textbooks and the two-volume History of Dartmouth (1932).

He had a reputation for grumpiness. His nickname, used both affectionately and derisively, was “Cheerless.”

He died a year after his wife’s death. He had a heart condition.

Skimming, unfortunately, requires too much restraint. Reading through this collection is like eavesdropping on a thin sliver of history. It’s metaphorical grave robbing: simultaneously intimate, sweet, nostalgic, and sad work.

Sometimes, I feel I am invading Leon’s privacy. At other moments, I feel like I am somehow honoring him. When else might someone squint at his small, neat handwriting and study his two grandfathers’ matching white beards?

I’m moved by the exquisite ornaments and accessories of his relatively ordinary life. I read, for instance, the letter Leon’s grandmother sent him when he was only 2 months old. “My little Grandson,” she writes, “How is your little face?” Yesterday, she adds, she saw a baby who looked just like him. Grandpa is sick but getting better. The mare is refusing to eat her hay. Her handwriting is scratchy and full of misspellings. He kept this letter all his life. He put it in his scrapbook.

I know, for instance, that at his graduation from Lebanon High School, he was given seven bouquets and six baskets of flowers (pansies, yellow lilies, roses, carnations). Five books. A silk handkerchief ($5). On graduation day, he expected he would grow up to become a criminal lawyer. He noted his bad habits of “smoking, chewing, and use of strong language.”

I read the letters he later sent his wife, Millie, from his travels across more than two decades. They are sweet, simple, devoted. In one, written from London, he describes the sky as either heavily overcast or dripping rain: “The reason why the English have been so venturous in exploration is a reasonable desire to get away from their weather.” “P.S.,” he adds at the end, “Aha! The sun is out as I write.” He follows with P.S. #2: “15 minutes later. It is raining.”

All his letters to Millie begin “My dear wife” and end “With much love.” I think he loved her, but I don’t know for sure. I can’t help the conjecture.

Leon kept his grandmother’s terse diary entry on his wedding day pasted on a page in his scrapbook. It reads, simply, “I suppose at 8 o’clock tonight Leon will be a married man.” A year later, in the same diary: “Leon’s birthday and Millie made him a present of a nice 8 lb baby boy, born about 4 o’clock this morn all doing well.” Another year later, she writes that she made succotash and, coincidentally, it seems, “Leon’s second baby born this afternoon.”

“For the hours that I am engrossed in the files, I say nothing, but my mind is loud.”

While visiting Hanover a few weeks ago, a friend of mine made a remark about archival research that stuck with me. She called this kind of research “social.” She described leaving the archives after a lengthy session as a slow emergence from a haze or coming up for air after a long time underwater. It’s true. It takes only ten minutes of head-hunched paging through Leon’s files before I am swallowed, deafened, by the chatter of his letters, essays, pamphlets, and all his ephemera.

In that noise, I can’t help filling in gaps, seeing his life as I imagine it. I also can’t help but notice what’s missing. He kept clippings of newspaper articles that mentioned his work, but he never saved one artifact from his children. There are all the carefully preserved letters he wrote his wife—but where are the letters she wrote back? His scrapbook is only half full. There’s a stack of papers in the center, items he never got the chance, or took the time, to paste onto the pages. His history, as he wanted to document it, is only half written. No one will ever finish it.

In 1951, the world had just passed the halfway mark of the century. Children were playing with Silly Putty. The Korean War was in full swing. Salinger published The Catcher in the Rye in July, and A Streetcar Named Desire premiered in September. On October 25, at Dick’s House, Leon died.

No more files. No more notes. His name will join countless others in archive and manuscript databases. At Rauner, he’ll become MS-505: the Leon Richardson Papers.

At the end of my workday, I will leave my desk and come up for air to return to the 21st century. Next week, Josh will hand me a new processing project, a new person’s files to “skim.” I’ll once again head-hunch into the files, back into that haze. And I’ll tell anyone who will listen that the sci-fi movies have it wrong: This is the closest thing we have to time travel.

Kira Parrish-Penny is the 2024-25 Edward Connery Lathem '51 Special Collections Fellow at Rauner Library.