Out of Nowhere

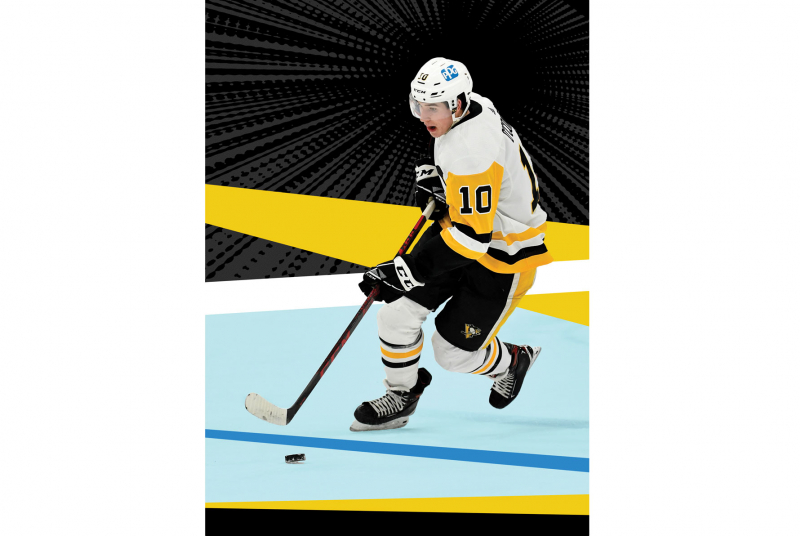

At 23, Drew O’Connor is the first Big Green player to crack an NHL roster since the last generation of veteran stalwarts Ben Lovejoy ’06, Lee Stempniak ’05, and Tanner Glass ’07 hung up their skates. Now in his second season with the Pittsburgh Penguins, the lanky winger with the hefty frame and boyish face is the first to say it: No one saw this coming, least of all him.

“It’s still something I’m not 100 percent used to,” O’Connor says, “the fact that I’m around some of these guys like Sidney Crosby or Evgeni Malkin—I grew up watching them, and now I’m having conversations with them.”

Drew’s father, Shawn, drove his boys to a Bayonne, New Jersey, rink in the predawn gloom every Saturday when they were kids. They took to the sport quickly, donning skates when they were still in diapers. Chasing his older brother, Jack, up and down the ice, Drew seemed to stand apart. By age 12, he was being invited to tournaments as far away as Edmonton, Canada, and Sweden. His youth hockey team made the U.S. national championships, and in the final game, Drew scored the winning goal.

“That’s where he was at 12,” his father recalls. “Then everybody grew—but he didn’t.”

O’Connor wanted to play for the elite team at Delbarton School, an athletic and academic powerhouse in Morristown, New Jersey. He was small but skilled and made the team, but he didn’t play much. During his junior year the squad reached the state championships. He spent most of the game on the bench.

His dream to play college hockey began to fade. He needed to be seen on the ice, or coaches wouldn’t come calling. As a senior, O’Connor left his high school team to play in a travel program. His game continued to improve. “I started to feel more confident, but I was graduating high school and had to decide whether I wanted to give up on hockey,” he says.

“He wasn’t getting any looks, even from Division III programs,” recalls his father, who suggested Drew move on with life and go to college. Instead, O’Connor decided to take a gap year and play more travel hockey.

During his first year playing juniors, he grew taller and, little by little, started to get noticed. Dartmouth assistant hockey coach John Rose spotted him at a tournament during the 2016-17 season and invited him to Hanover. The coach offered him a spot on the team—the only offer O’Connor received.

Dartmouth recommended a second year of junior hockey with the Boston Junior Bruins. O’Connor was 5-foot-10 when he left high school. A year later, he stood at 6 feet. Following a shoulder injury during a game, an ER doctor checking his X-rays told him he would grow another inch or two. By the time O’Connor arrived on campus in 2018, he had grown 3 more inches.

At his first game, against Harvard, he scored a breakaway goal and had three points in the 6-5 overtime victory.

By his sophomore year, O’Connor was no longer anonymous in the world of college hockey. He became the fourth player in Dartmouth history to win the Ivy League Co-player of the Year. A real highlight came back in New Jersey, where more than 40 of O’Connor’s relatives packed the Princeton arena for the Dartmouth game just after New Year’s in 2020. “The O’Connors were the loudest people there,” he recalls. He scored the game winner in overtime.

Scott Young, director of player development for the Penguins, remembers traveling north to Hanover to see this kid his local scouts had been pestering him about. “When a player puts up that number of goals, it just draws everybody’s attention,” Young says. He had heard rumors that O’Connor was talking to other clubs about leaving college. After the game, Young made his pitch: “If there’s any chance you would leave, we have to tell you how much we would love to see you in Pittsburgh.”

O’Connor wrestled with the decision to turn pro. His freshman seminar with professor Douglas J. Moody on mural art in Mexico had drawn him in, and he planned to major in sociology. He had forged fast friendships at Chi Heorot and enjoyed regular swims and kayak runs on the Connecticut River.

“But it was such a tough opportunity to turn down,” he says. “I decided maybe two weeks before our season ended. We lost to Princeton in the ECAC playoffs, and I signed two or three days later.” Then Covid-19 forced the cancellation of all Ivy League sports. “It was easier on me once I saw they weren’t going to play the next year,” he admits.

The pandemic also altered the Penguins’ plan for O’Connor—they had intended for him to play on a minor league team to help him adjust, then crack the roster in Pittsburgh the following year. Instead, he traveled to Norway to play a limited schedule of hockey in Oslo. It was the only place he could find real time on the ice.

He returned to the United States and played his first NHL game on January 26, 2021, against the Boston Bruins in an empty TD Garden. As his parents gathered at home to watch on TV, the doorbell rang. The Penguins had sent a gift basket and congratulatory note.

O’Connor played in 10 NHL games that first year. This season, he’s adapting to life in the pros. “Usually the planes are pretty fun—play some cards, things like that, hang out with the guys,” he says. One difference, though, is that he has continued to take classes via Zoom. “Other guys are playing video games or sleeping or trading stocks to pass the time,” his father says. “Drew was a full-time student.” O’Connor hopes to walk at Commencement with his class in June and finish any remaining credits this summer.

For a player whose career has far outpaced his expectations, O’Connor says he’s not going to guess what will come next. “I have no idea,” he laughs. “I’m playing in a league with all these players I watched growing up. From that perspective it’s pretty cool. But after this? I don’t know. I’m just going to enjoy being here right now.”