House Call

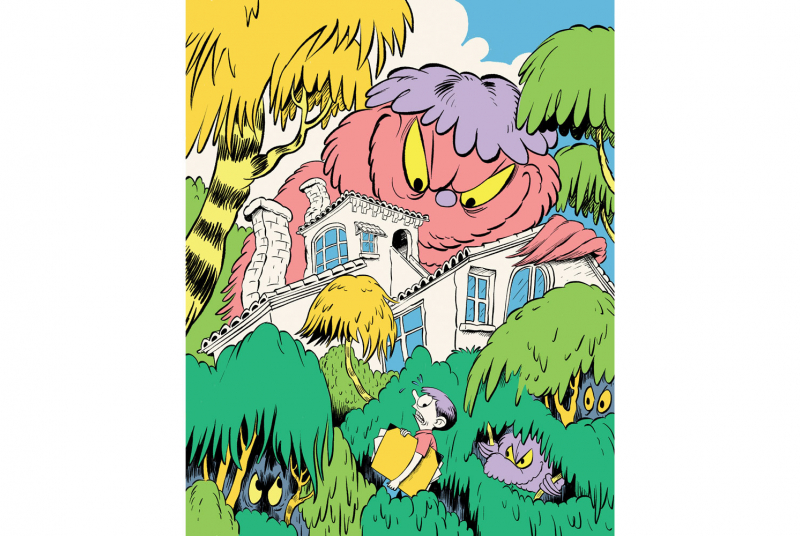

What kind of fantastical creatures might guard the property of Dr. Seuss? That’s what I was about to find out, one day back in 1985, as I stood fearfully before his home and contemplated my intention to willfully trespass.

In front of his magnificent hilltop home in La Jolla, California, I paused. Though the property wasn’t fenced, signs warned against entry and threatened a response by security. That’s when I got thinking about Seussian creatures that might be patrolling. I took careful steps across the immaculate lawn. I anticipated trouble coming my way, but until it did, I was determined to approach as close to the house as I could in hope of a lucky break.

After I left Dartmouth, my career goal was to become a restoration architect. Before graduating I secured a grunt job with a reputable contractor in Newport, Rhode Island, with hopes of getting field experience before moving on to an advanced degree. When I spoke to the architects there, however, they lamented the years they had to work before they got any career satisfaction. I sent a lackluster application to grad school and was denied entry.

When I got laid off, I resorted to doing something I always loved: drawing cartoons.

To turn cartooning into a paying job, I needed guidance. In the spring of 1984 I contacted legendary Rhode Island cartoonist Don Bousquet, who was enjoying success in Yankee magazine. I found his phone number and was pleasantly surprised when he answered my call. Flattery got me an invitation to his home. During my visit Bousquet, who remains a mentor and friend, showed me how he created his cartoons. He took a critical look at my work and advised me to find a place—any place—to get published and paid. Experience, he felt, would steadily improve my skills.

In the fall I played a long shot by writing to Theodor Geisel ’25, a.k.a. Dr. Seuss. I figured the odds of his replying would be shortened by the fact we shared an alma mater. I got his address from the alumni office and reverentially wrote a request for direction. I included copies of my best work.

Within a short time I received a special piece of mail. The stationery was light blue with a one-line return address: Dr. Seuss. In his two-page, typed letter Geisel encouraged my pursuit of a career as a cartoonist. He urged persistence and noted his own struggle to find a publisher for his first book. He told me to keep the mailman busy by sending work to prospective publishers. I was astonished that he would take the time for such a thoughtful reply. I had gained another mentor.

Dutifully following the advice of both men, I went on a quest for publication. I sold my first drawing in March 1985 to the Phoenix-Times Newspapers based in Bristol, Rhode Island. The drive to and from the office to pick up the $8 check likely consumed the proceeds, but at 23 I had become a professional cartoonist.

My modest success inspired a desire to meet my unmet mentor. In the spring of 1985 I planned a trip to southern California to visit friends with hopes of including my famous pen pal in La Jolla on the itinerary. I wrote Geisel to request a meeting, but I didn’t hear back.

I had his address. I had warned of my intentions. I felt justified.

I had his address. I had warned of my intentions. I felt justified. I went to his neighborhood and decided to risk offense by dropping in without invitation. Accompanying me was Dave “Weasel” Badger ’83, my four-year Dartmouth roommate. Badger, one of my California hosts, liked the idea of seeing where Seuss lived. I would go in alone and he would wait in the car.

I started across the lawn. When I got near a large picture window I saw a woman, possibly Audrey Geisel. By her expression and rapid grab of a phone, I concluded my luck had run out. Then a bearded, gray-haired man rose beside her and seemed to instruct her to hold off on the call. It was Geisel, who looked out to find me going into a pantomime to indicate that I was the guy who had written about visiting. He interpreted my act and waved me to the back of the house.

I nervously moved into a courtyard that featured an impressive pool and dramatic architecture. As I stood still on the pristine patio, Seuss came toward me. He looked grizzled, like a man who hadn’t left his house in a long time. He was kind in his approach, extending his hand as I identified myself. In a hoarse voice he let me know that he figured it was me. He had gotten my note. After initial pleasantries I asked if we could sit down and talk. He said it wasn’t possible. He had pneumonia and was headed for the hospital that afternoon. I understood and once again shook that marvelously talented hand, thanking him for his kindness. I then retired across the lawn, still jittery about what might be following me.

After returning home I received another piece of mail from Seuss. It was an apology sent by his secretary, letting me know that he had been very ill the day I visited and that he’d spent time in the hospital but was now much better. She wrote that Seuss wished he could have spent more time with me.

In July of 1991 I received my last note from Seuss, this one handwritten. That spring I had sent him a package that included a copy of my first nationally published cartoons. They appeared in Volleyball Monthly Magazine and were printed with a short biography. The bio mentioned that my own volleyball team was called the Cross-Eyed Flies. Geisel included a cartoon of his own. On his Cat in the Hat stationery, Geisel had drawn a dialogue bubble from his mascot with the announcement, “Our Favorite Team in the World of Sports is the Cross-Eyed Flies!” No doubt he sensed his influence in my choice of our team name. His note included a benediction for “the next six decades of upwardses and onwardses!”

Today when I’m drawing with hospitalized children in my role as resident cartoonist at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, I often hear, “Hey—that looks like something Dr. Seuss might have drawn.” My reply is always, “You couldn’t have given me a higher compliment.”

Steve Brosnihan lives in Rhode Island.

Illustration by Zohar Lazar