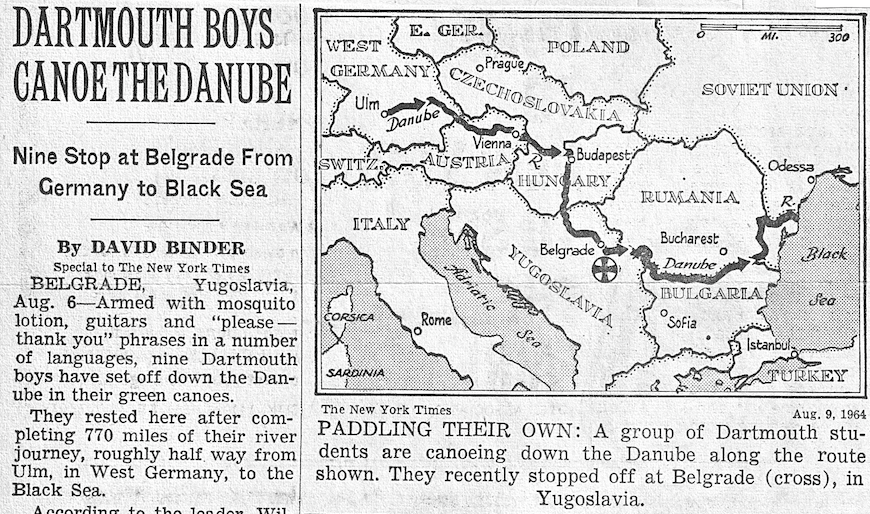

In the summer of 1964 nine Dartmouth students steered their canoes behind the Iron Curtain in an effort to promote cultural exchange between East and West. The 1,650-mile trip down the Danube started in Ulm, Germany, and ended in the Black Sea, at the border between Romania and the former Soviet Union. DAM recently spoke with the trip’s leader, Dan Dimancescu, about his Ledyard-inspired journey.

Article on the Danube expedition in the New York Times, August 9, 1964

Where did the idea for a Danube River canoe trip originate?

The origin of the idea came in the fall of 1963. I took a solo canoe trip on the Connecticut River—it was one of those nice fall mornings when there’s a little bit of fog on the river—and the idea of canoeing down the Danube just came, literally, out of the blue.

Had you ever been to the Danube before?

No. I was born of Romanian parents during World War II in England. I had never been to Romania, but at home there was always an awareness of wanting to go to Romania. This was one of those magical moments where it was like, “Why not get there by canoe?”

Did you have any prior experience with long canoe expeditions?

No, my canoe experience was all at Dartmouth. I was a transfer student and came to Dartmouth my sophomore year. I met Chris Knight ’65, who was already an avid kayaker, and he introduced me to kayaking in the middle of winter on the Connecticut River, which is not something I recommend to anyone. I then teamed up with Bill Fitzhugh ’64 and we became whitewater canoe enthusiasts. I joined the Ledyard Canoe Club and we competed a lot in whitewater races. My longest trip was actually the famous downriver “Trip to the Sea,” which I did one time.

Dimancescu and Edmund “Terry” Fowler ’64 (Romanian National Tourism Office)

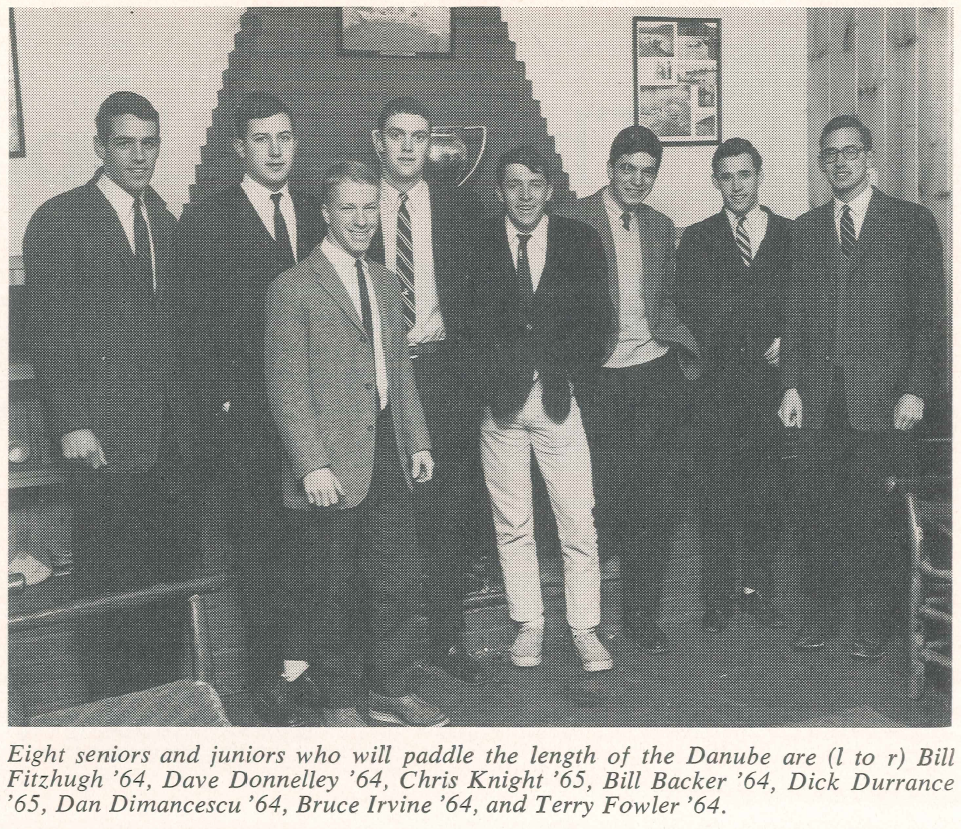

How did you select the members of the Danube expedition team?

Fitzhugh was the first obvious teammate. We started inviting people who weren’t necessarily Ledyard Canoe Club members but who could bring different assets to the trip for fundraising and photographic skills. Knight was a good photographer. Dick Durrance ’65 came on board and then others—some with musical talents, some with medical skills. We built the team around talents rather than actual membership in the club.

Members of the expedition featured in DAM, February, 1964

Did your parents or professors worry about you making a trip behind the Iron Curtain?

My parents were from a much older generation. My father was born in 1896. He left Romania because of the communist takeover. I think, for my parents, there was never any thought of returning there for themselves, and they looked upon this trip with great pride, not trepidation. Given that we eventually got National Geographic support, that was a comfort level. And the U.S. State Department was extremely helpful, so that added another layer of security to our trip.

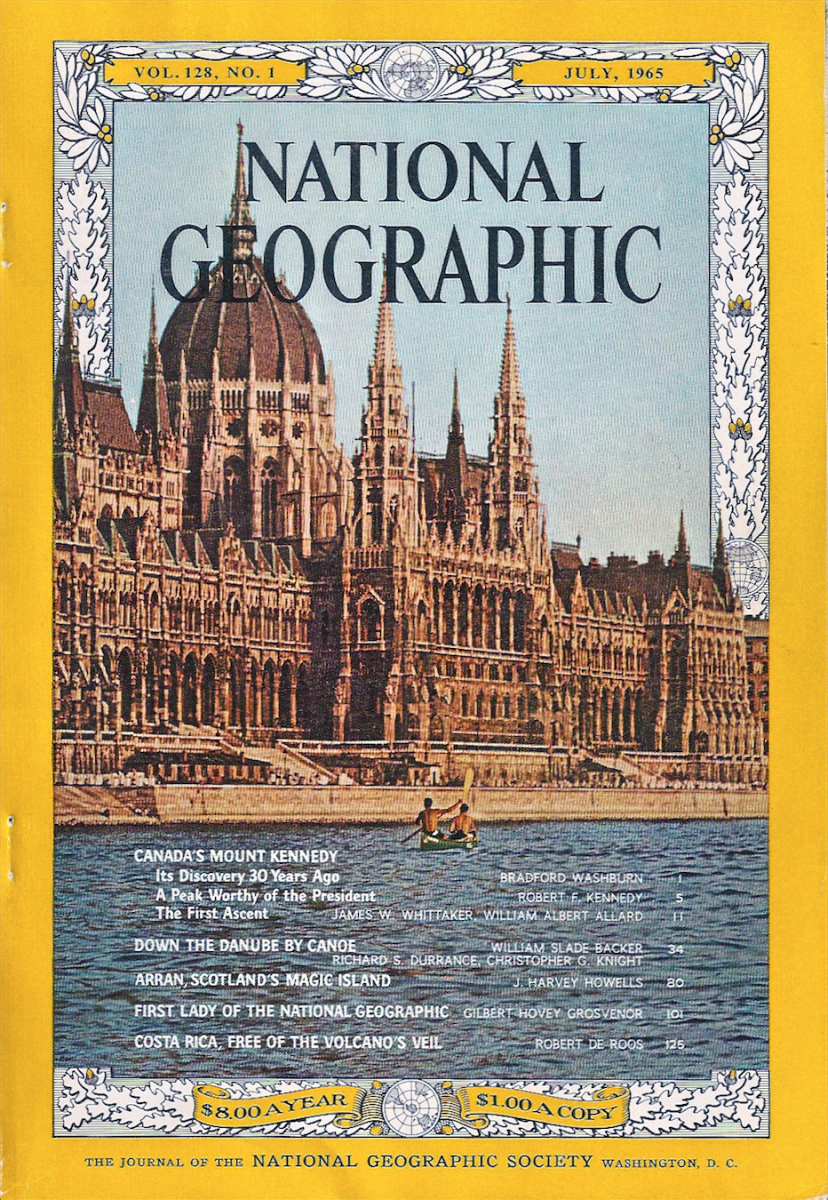

Cover story on the Danube expedition, National Geographic, July, 1965

How did National Geographic get involved with your expedition?

That was one of those lucky breaks. Both Knight and Durrance are from well-known photographic and film families, and both had relationships with National Geographic. That opened the door for the photographic editors who make decisions on these kinds of trips. The way the Geographic works, if the photographers are good and the story sounds good, then they come on board. The writing becomes secondary. They don’t choose stories by writers but by the quality of the photographers. So we were very lucky that Chris and Dick had professional skills at a young age.

How did you acquire funding?

That was another reason why we chose some of the team members. I became roommates with David Donnelly ’64, who came from a well-known family that owned one of the country’s biggest printing companies. Donnelly was very effective in helping us fundraise.

The February 1964 issue of DAM reported that one of the members of your team was in a liquor store, chatted up a few women, and they gave him $500 on the spot for the trip. Is that true?

That was Donnelly. I assume that’s a true story. That’s the way he told it.

DAM also reported that they offered him another $500 if he became fluent in German before the trip.

Well, we probably did not get that second check.

Did you need special permission from the State Department to gain entry to the communist countries?

Absolutely. We had a couple of lucky breaks. The first was ex-ambassador Ellis O. Briggs ’21, who had retired in Hanover. He was our introduction into the State Department. They didn’t do anything exceptional for us other than bless the trip and make sure that along the way we would be taken care of. The second break was rather unusual. We had a travel agent in New York who catered to East European tourism, including the communist countries. At the very end of our pre-departure we still didn’t have visas for a couple countries, and he managed to negotiate those for us at the last hour. It was those kinds of details that made the trip possible.

Bruce Irvine ’64 and William “Slade” Backer ’64 (Richard Durrance and Christopher Knight)

Did you undergo any physical training or language studies to prepare for the trip?

We didn’t do anything physical, because canoeing is not exceptionally hard. It’s just endurance rather than extreme effort. Each one of us took a country and then spent effort trying to make contacts, trying to find canoe clubs and learning a bit of language. That took a lot more preparation. Fitzhugh was really good in preparing the canoes. It took a lot of effort to create what are called “wanigans” (wooden cases) to store our equipment. We also had special water-covers on the canoes. All of that took a lot of thinking and made a huge difference.

Why did you bring canoes from the United States instead of using what was available in Europe?

It made sense that if we’re Americans then we should go with American canoes. One reason that we used American canoes is that they’re extremely comfortable for long trips. You can carry a lot of equipment, you can lie down in them, you can jump in and out—they are very versatile boats. We got in touch with the Old Town Canoe Company in Maine, and they were very generous to donate the canoes.

Did you sleep in the canoes?

No, we wouldn’t sleep in them at night, but during the day we’d just drift with the current. We’d lie down and drift in the current or have lunch, or whatever.

What did the locals think of a group of men canoeing past their homes?

In the western part, meaning Germany and Austria, people just couldn’t believe we were going all the way to the Black Sea. First, because of the Iron Curtain, and second, because of the distance. They were awed that we were going that far. In Eastern Europe it was very different. On one level, you get the authorities, meaning border guards and officials, who didn’t know what was going on. We had all the official authorizations, so that got us through. With local people, it was just pure fascination that some American guys were showing up at their canoe club or in a village. That enthusiasm grew the further down the river we went. As we got into [former] Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Romania, huge crowds would gather wherever we camped out. They would touch the textile fiber of the tents, they would look at our clothes—it was just like people from another world appearing in their villages.

Crowd gathered in Bulgarian village (Richard Durrance and Christopher Knight)

Did you have guides to help you navigate any of the territory?

In the communist countries we always had to have someone accompanying us, usually young people in boats, who had to report to the authorities what we were doing. All of them were very nice people. They never interfered. They didn’t really serve as guides as much as translators and door-openers if we had to get an official stamp for a visa or permit. They were all very open-minded and not obstructive. When we finished the trip, we invited several of them to come to the states and we did a Hudson River trip a year later to thank them. The only country that didn’t allow us to enter its territory was the Soviet Union, which bordered the delta at the end of the trip.

What was the most challenging aspect of the whole trip?

Just enduring the distance. I think on our maximum day we paddled 80 miles. Just from a physical exertion point of view, that’s a lot of miles. Further down the river gets very wide, very boring, and so you’re putting in long days under the sun. I don’t think we ever complained about the physical effort. The only minor and almost humorous part was when we reached the delta of the Danube, which is a pretty wild area, and we ran out of food. The real crisis was for Durrance, who ran out of peanut butter. He was very, very sad not to have peanut butter. That’s the part of the river where we ate frogs for dinner.

Dimancescu, Fitzhugh and Backer on Mount Strbac, the highest point along the Danube (Richard Durrance and Christopher Knight)

Did you select any members of your team for their cooking abilities?

No. All of us had had camping experience, which is a Dartmouth thing, so if we cooked over a fire it was Dartmouth-style and everybody would pitch in. The best job on the trip was to go buy food in villages because you could stuff yourself before you got back to the campsite.

Did you make contact with any of your Romanian relatives?

Absolutely. On my mother’s side there was a very large family who go back about 500 years in Romania. On my father’s side there were less people because there had been abuse of the family during communist times. At one point in the trip I took two days off and went up to Bucharest just to meet my family.

What did the expedition achieve?

In a modest way, our trip brought into view a profile of young Americans to many people who had either never seen Americans or who had hoped for a never-to-come American rescue from communist rule. On a personal level, the expedition was life changing for all nine of us.

What is your favorite memory from the trip?

The favorite memories are river-side camps, particularly in the communist countries, where our presence would create spontaneous crowds. This would quickly turn into musical events paced by our guitars, singing and friendly encounters. Much of this was outside the control of government handlers, given the remote villages sites we encountered. Also memorable was a side trip to experience the famed and dramatic rapids of the Drina River in Yugoslavia. A 14-hour steam-train ride took us and our canoes up into the mountains to a launch down the deep gorges and fast waters of the Drina. Little could one guess that decades later the same river valley would see such incredible violence and bloodshed during the Bosnian/Serbian war.

Do you have any other big expeditions planned for the future?

In recent years my adventures have been more in the category of documentary filming—though, they could be called “expeditions.” My son started a film company in 2008. I organized and he directed two feature films, and then started a third in Romania. Tragically, he died accidentally at age 26 during filming in the Carpathian Mountains in 2011. His young colleagues and my family decided to keep his Kogainon Films company going. We’ve since done more production work and look forward to the next adventure.

Dimancescu at the 50th anniversary exhibition at the National History Museum of Romania, June 2014 (Courtesy Dan Dimancescu)

James Napoli is Digital Editor at Dartmouth Alumni Magazine.

Top photo: Canoes in mid-river of the Iron Gates between Yugoslavia and Romania, 1964 (Richard Durrance and Christopher Knight)