By 2011 only two of the world’s 50 highest mountains remained unclimbed. One of them, Gangkhar Puensum in Bhutan, was permanently closed to climbing by the government. The other, Saser Kangri II, rises from the eastern end of the remote, deeply corrugated Karakoram Range in the contested border territory between India and Pakistan, an area that had only recently been opened to climbing and the outside world. The mountain’s only possible ascents required highly technical climbing on both rock and ice—climbing that became steeper and more difficult as it approached the 7,518-meter (24,665-foot) summit. To all but a small class of alpine climbers, Saser Kangri II remained virtually unassailable.

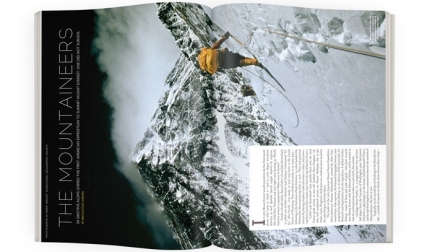

That summer the American team of Mark Richey, Steve Swenson and Freddie Wilkinson skied out of the Nubra Valley over a 20,000-foot pass and established an advanced base camp on the South Shukpa Kunchang Glacier in preparation for a try at the summit. In stark contrast to the commercially guided, fully supported ascents that had come to define modern high-altitude mountaineering, the alpinists were traveling light. They planned to make a sustained five-day summit push up the mountain’s sheer southwest face without fixed camps or ropes. They would carry all of their gear with them, calling on a full spectrum of mixed climbing and survival skills.

Two of the climbers, Richey, 57, and Swenson, 53, past and current presidents of the American Alpine Club, had stood on the flanks of Saser Kangri II once before. As part of a first attempt in 2009, the seasoned climbing partners had wasted precious time and energy searching the steep southwest face for ledges that could support the bivouacs needed for the multi-day push. They’d made it to 6,500 meters before being turned back by bad weather. Their experience on that failed expedition provided critical information for the 2011 attempt.

In filling out his new team Richey knew he would need someone whose strength and technical skill would be assets on the difficult climbing above 6,000 meters. Someone whose judgment and character could stand up to a place where the margin for error is as thin as the air.

He reached out to fellow New England climber Wilkinson, who at 31 was young enough to be Richey’s son—and young by mountaineering standards for high-stakes, high-altitude climbing. Wilkinson had climbed Denali via the Cassin Ridge while he was still a student at Dartmouth. In his 20s he’d established new routes on mountains on three continents. He’d joined the tiny fraternity of rock climbers who had completed Yosemite’s two iconic big-wall, multi-day climbs—Half Dome and the Nose on El Capitan—in less than 24 hours. He’d apprenticed himself with the world-class guides and volunteers in the Mountain Rescue Service near his home in New Hampshire’s notoriously inhospitable Mount Washington Valley. In an era when the pursuit of high places was becoming segmented into ever-narrowing niches of indoor climbing, bouldering, sport climbing, “trad” climbing, ice climbing, high-altitude mountaineering and ski mountaineering, Wilkinson was a throwback. He was skilled in all of it.

On Saser Kangri II, Wilkinson broke trail and did much of the heavy lifting that would be expected of the youngest team member. But his partners relied on his judgment as well, deferring to him on route-setting and, on the crucial second day of the summit push, following his advice to keep advancing as they looked for a potential bivy site to spend the night. He was the one who powered through the “Escape Hatch” on Day 3, a key passage that unlocked the upper portion of the climb. A day later, on August 24, Wilkinson was breaking trail on the final approach to the summit when he stopped and let Richey catch up and then pass him. “This was a mountain he had discovered,” Wilkinson later said. “I knew how much it meant to him to be the first one up.”

On its website, Alpinist called the achievement “one of the highest first ascents of a peak in alpine style in the history of mountaineering.” In Chamonix, France, the following spring, jurors for the prestigious Piolets d’Or selected two first ascents of 88 nominated from around the world that best embodied the spirit of exploring remote and technically difficult mountains, of pioneering imaginative new routes in lightweight and low-impact style, and of embracing the ideals of commitment and teamwork. The Saser Kangri II climb was one of the two. The judges called the expedition “an example of classic exploratory alpinism and committed alpine-style climbing at high altitude.” In the history of the award only five Americans had previously received the honor.

“For an alpinist,” Wilkinson said after the awards ceremony, “hiking into the eastern Karakoram was like walking into a candy store. Just getting to base camp was a full-blown adventure. The chance to go and climb a 7,500-meter peak, and making the first ascent alpine-style, was an opportunity I probably will never have again. To stand on the summit was incredible.”

In New Hampshire Rick Wilcox heard the news of the Piolets d’Or and took some pride in it. Owner of International Mountain Equipment (IME), with its highly regarded climbing school and guiding service, Wilcox remembered Wilkinson coming up from Connecticut as a 13-year-old to climb his first mountain. “Bad weather came in on Mount Washington,” Wilcox recalled, “and Freddie thought it was exciting. His father didn’t like having to dig out a snow cave, and Freddie loved it. There’s a certain sense of adventure that true climbers seem to be born with—Freddie had that from the start.” Wilcox later hired Wilkinson to guide for IME while Wilkinson was still studying history at Dartmouth and brought the young climber into the tight-knit community of guides and rescue volunteers who live in the Mount Washington Valley. “The thing I like about Freddie,” says Wilcox, “is that there’s a grounding in a style and a set of ethics that make him the climber he is. He never takes shortcuts or uses others to bring the mountain down to his level.”

“The award,” Wilcox adds, “is like winning the Super Bowl of climbing. Freddie’s broken into a level where he’s automatically respected by elite climbers around the world, which is very unusual at his age. It will be interesting to see where he goes from here. I have a feeling that 10 years from now we’ll be looking back at the 10 years Freddie’s just had, and we’ll all be saying, ‘Whoaaa....’ ”

There’s a saying among climbers: “The bigger the mountain, the bigger the ego.” There was reason to wonder if the experience—or the rarefied company that Wilkinson had suddenly joined—would change him. On a summer day last year in Evans Notch, near the New Hampshire-Maine border, watching and hearing Wilkinson climbing on a little-known crag with a couple of old friends, it was safe to say not much had changed. The three of them took turns scaling difficult, single-pitch climbs rated 5.11d and 5.12a/b in the climbers’ lingua franca. Their voices rang above the rush of a brook near the base of the cliff: “Way to go J.T.! You crushed it!” Wilkinson yelled as Jack Tracy, 55, finished off a textbook iron cross at the crux below a long scoop on the first route. Wilkinson took a turn and practically flew up the face, then paused before the crux. “Nice, brother. You got it. Slap it!” Tracy shouted.

Two decades younger than his climbing mates, Wilkinson looked the part of the dirtbag climber, scruffy, shirtless, lean and wiry. He wore a faded baseball cap when he wasn’t on the rock. He wore plaid shorts, along with a leather necklace with a ring hanging from it.

On the ground the three men bantered about the problems of fixed draws and congestion, about new ropes and other climbs they wanted to do together. Wilkinson had carried in a six pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon and left it cooling in the brook. They drank beer together as an afternoon shower moved in and sent them trudging back down the muddy trail. Wilkinson seemed animated, psyched to be outside, even in the rain. “That’s my first new 5.12 this year. I haven’t gotten out much,” he said to Tracy, grinning.

“Not bad coming off the sofa,” Tracy said, and for all the world the three of them seemed like equals.

But Wilkinson’s life was changing. The ring on his leather necklace was a silver wedding band; he’d recently married his long-time girlfriend, climber Janet Bergman. He’d been busy the past many months—wearing a tool belt more than a harness and swinging a hammer more than an ice ax—on a new home on their 13 acres in the town of Madison, New Hampshire, a real house with bedrooms and heat and running water that will replace the primitive 12-by-12-foot, one-room cabin the two have been sharing on the land since 2007. “I don’t mind hauling water, actually,” he says, “or the watering-can showers. But I can’t wait to be able to wash dishes in a sink like a normal person.” Bergman, after years of seasonal and freelance work, has started a nonprofit business.

Wilkinson is already making a full living around his climbing, something Wilcox estimates that only 1 or 2 percent of all climbers can pull off. He’s supported by corporate sponsors such as Mountain Hardware, Clif Bar and Sportiva in return for representing their brands and providing content for their marketing. In that sense he’s not a throwback at all, but a 21st-century professional adventurer with new, requisite technical skills that include sport photography and videography. His film of the Saser Kangri II expedition premiered earlier this year at the annual 5Point Film Festival in Carbondale, Colorado. The documentary isn’t as much a celebration of the team’s success as it is a tribute to the two remarkable amateur alpinists he climbed with, men in their 50s who have family lives and full-time jobs and have world-class adventures on their vacations. Wilkinson took for its title the name they gave the route up the mountain’s steep, unforgiving southwest face: The Old Breed.

He guides 40 to 50 days a year, most of it locally, with private clients. (“I like people who climb in the Northeast,” he says. “Plus I like the variety and extreme conditions, even while I can end up most nights back at home in my own bed.”) He gives a couple dozen talks and slide shows throughout the year—at high schools, on college campuses, for organizations. Perhaps most important to him is that he represents the conscience of a sport through his magazine articles and other writing. In November he embarked on a National Geographic-funded expedition to the mountainous interior of Queen Maud Land in East Antarctica, one of the most remote and expensive destinations on the planet.

His book about the 2008 tragedy on K2, where 11 lives were lost, put him on a different map: as a legitimate writer in his own right. One Mountain Thousand Summits (New American Library, 2010) is a dramatic, sensitively researched exploration of the cultural dynamics that played into the final disastrous hours of the K2 expedition. It tells the story of the climb in large part through the perspectives of the Sherpa guides whose roles had been overlooked or misreported in the media.

The genre of high-alpine literature flourished in the 1950s, when the model was single, “official” accounts of expeditions. It broadened in the 1970s when multiple accounts of the same expeditions added nuance and alternate perspectives—and exploded in the Internet age with real-time blog posts that seemingly captured the truth and immediacy of events that only in-the-moment reporting could deliver.

Wilkinson, having been there, pushed past that. He knew better, knew how unreliable real-time accounts from chaotic, hypoxic, sleep-deprived mountaintops can be. His book debunks many of the early Internet-based reports that flowed out of the K2 tragedy—reports that clouded later newspaper and magazine reporting. He showed that the need for self-promotion and the desire for speed in getting out the story had trumped all attempts at the more difficult task of piecing together what really happened—and made the task more difficult at the same time.

In a May 2012 op-ed for The New York Times, Wilkinson planted his flag on another controversial topic: the increasingly dangerous conditions on Mount Everest, where a warming climate has increased the risk of accidents, and the overwhelming number of unqualified climbers on the mountain almost guarantees them.

The current scene on Everest is a world away from the kind of pure alpine mountaineering Wilkinson is dedicated to, and some have wondered why he even bothers himself with it. The fact that he cares sets him apart. He is distinguished from his peers, perhaps, not only by the breadth of his climbing skills, but also by the moral compass that guides him.

At a literature festival in Banff, Alberta, he gave a reason for caring. “We all have a stake in the stories that get told about these 8,000-meter mountains,” he told the audience. “Whether we like it or not, the general public will always see them as representing climbing. Our stories show the world what our ethics and values are as a sport—and as a community.”

Jim Collins is a former editor of Yankee magazine. He lives in Seattle and Orange, New Hampshire.