If I had to identify my first footstep in my journey from American emigrant to Canadian immigrant, it would have to be April 14, 1966, and the arrival on campus of Gen. Lewis B. Hershey, director of the Selective Service, the U.S. draft. Vietnam, once the name of a country, was now indelibly the name of a war. It was on all of our minds, politically and personally. But these were very early days.

Protesters outside the Hopkins Center wore jackets and ties, and Hershey received a generally polite reception. Spaulding Auditorium was jammed. Most of us were there to learn about the various deferments that might keep us out of the war. I remember very little of the ground Hershey covered, but I do remember, viscerally, the question-and-answer period that followed.

The first questioner asked why the rest of the country should remain commit-

ted to a war that our government clearly couldn’t contain. Hershey’s answer went something like this: “You must remember that the president is not only our commander-in-chief. He’s also like a quarterback in a football game. You don’t replace the quarterback in the middle of the game merely because a few of his plays don’t work. Next question?”

A voice cried out, “Oh yeah? Well let’s hear it for Hitler, Himmler, Goebbels and Göring, whose brilliant teamwork won them 6 million touchdowns!”

I would so love to learn whose voice that was. His heckle became a pivot-point that shaped the rest of my life.

It’s been said since that the instant a debater attempts to compare some contemporary evil with the Holocaust, all reasonable discussion is over. But in the 1960s the comparison still had resonance, especially when it came to blindly following orders—a defense clearly rejected at the Nuremberg trials.

I began paying close attention to the war, where it came from and where it was taking my country and, possibly, me.

On my next trip home to New Jersey, I picked up a conscientious-objector application at my local draft board. After three hostile hearings, my draft board granted me 1-A-O status. This meant I could be drafted at any time, but once in the military I would not be issued a weapon. Instead, all 1-A-Os were shipped off to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, and trained as hospital corpsmen or battlefield medics.

I rolled the VW a few more feet into the promised land, got out and kissed the ground.

I’d come to Dartmouth with the vague idea of learning about theater, but I was spending less time at the Hop and more at Robinson Hall and the studios of WDCR. I saw in radio a chance to learn both an art and a craft that I might shape into a serious career. Actors might wait a decade between good parts, but in radio I could be on every day, with that day’s tape as my feedback loop. Plus, in radio I would never lose out on an audition because I didn’t “look the part.”

My Dartmouth education would be invaluable throughout my career, but it was my extracurricular time at WDCR that gave me a sense of what I might actually do with that education, while giving me a safe place to make all my on-air mistakes. At the end of my senior year I went right to work at the obligatory 500-watt starter station, in Hartford, Connecticut. In less than a year I’d graduated to 50,000 watts, in Washington, D.C.

In April of 1969 I was drafted and sent to Fort Sam to train as a medic. By this time the war was chewing up lives by the thousands, and many of the medics who trained before me were returning home in body bags. In late 1969 I got my orders to report to Fort Lewis, near Tacoma, Washington, on December 23 for shipment to Saigon.

Back at my parents’ home, advice flooded in. Some Boston lawyers suggested I stay put, go limp and refuse to be moved. I might be put in the stockade for a couple months, but they would soon plea-bargain me out of the Army. A Manhattan psychiatrist’s contribution to the cause was to write letters predicting a mental breakdown should the Army send his patients into combat.

What could I do? Sweden, I knew, was welcoming war resistors by the hundreds. My wife-to-be, Mary Cone (Sarah Lawrence, class of 1967), had lived in Stockholm on a high school exchange and spoke some Swedish. It was a possibility. Canada was accepting draft-dodgers by the thousands, but as we’d been warned many times at Fort Sam, AWOLs were being turned back at the border. What the brass at Fort Sam didn’t know, or didn’t want us to know, was that Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government had announced that all mention of military service would henceforth be removed from Canada’s immigration policy.

The American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker pacifist group, saw to it that word went out to soldiers at U.S. Army bases all over the world. As a consequence, thousands of GIs—including me—made their way to Canada.

I’d never been there and had no idea what the situation at the border would be. All I knew about escaping dissidents came from the daily stories of Germans virtually imprisoned behind the Berlin Wall. Like them, Mary and I thought we’d be stopped by American military police, who would turn us back if our papers were not in order.

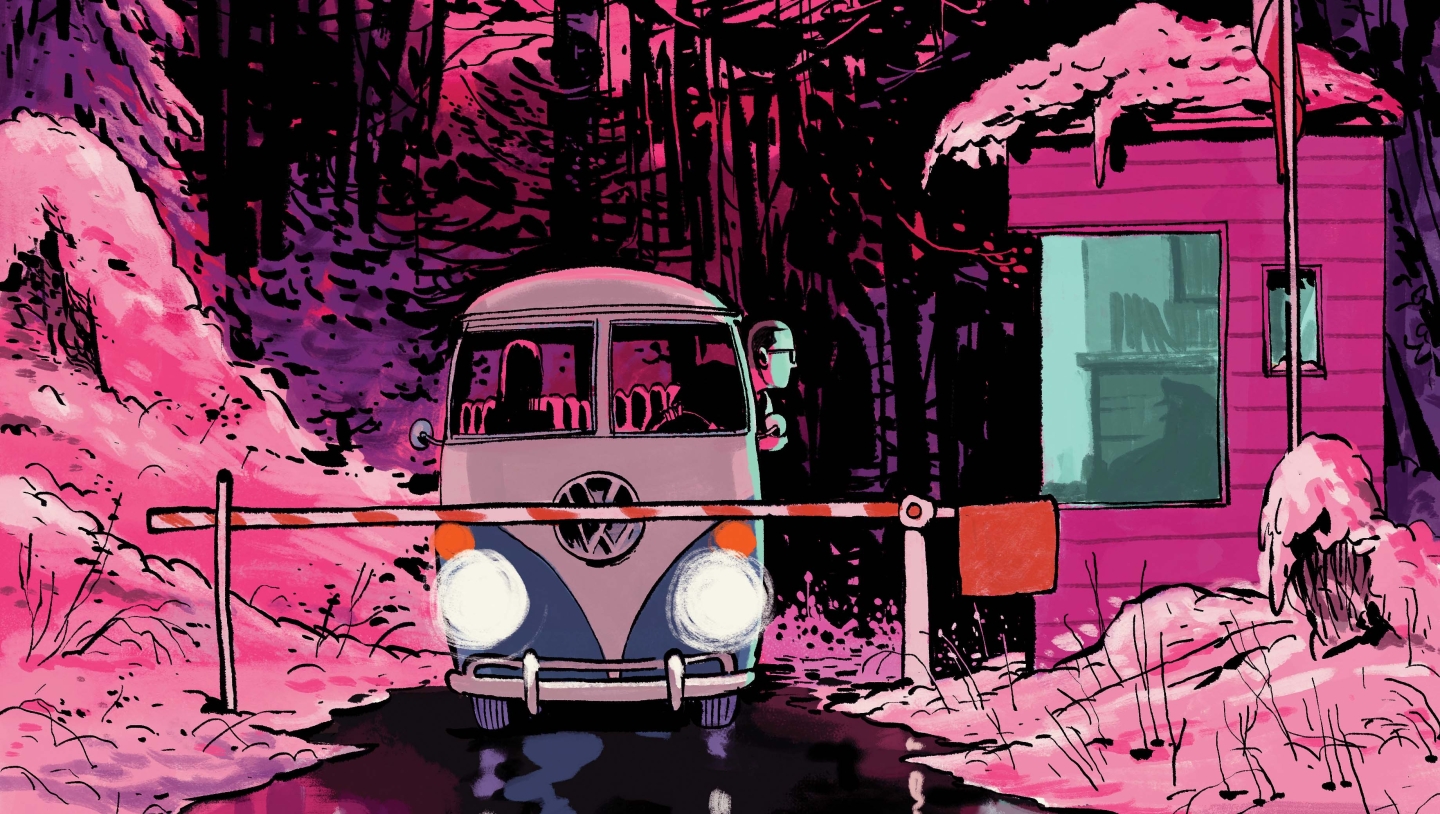

At Derby Line, Vermont, chosen because it was said to be the least-traveled border point for hundreds of miles, we were to make our stand. I was prepared to gun my VW’s engine and barrel through any obstruction. This would be our Checkpoint Charlie. As absurd as this might seem now, nothing prepared us for the mindset of refugees on the run.

If you’ve ever traveled by car to Canada, you know you see no officials until you’ve actually left U.S. soil. As the border disappeared under our wheels, we found the single Canadian officer snoozing at his desk. Waking him up, we volunteered that we were on our way to a ski holiday. “Have a good time,” he said, and waved us on.

And that was it. I rolled the VW a few more feet into the promised land, got out and kissed the ground.

By Christmas Day I’d found a place to live, splitting a $9-a-week room near McGill University with a guy I’d met in a coffee shop. That week I met a reporter from CJAD, Montreal’s top radio station, and wound up in the office of its general manager, Hollis T. “Mac” McCurdy. When he asked what brought me to Montreal, I said I’d deserted from the U.S. Army to stay out of Vietnam. I expected a trapdoor would open, depositing me outside on the sidewalk. But without skipping a beat, McCurdy asked my age, marital status, etc. Only later did I learn that he was a WW II veteran who had trained pilots in England for the Royal Canadian Air Force.

McCurdy asked me to audition that day. I was told my American accent was too strong. I would have to work on it. By April my “outs” sounded sufficiently closer to “oots” that I could be safely offered the munificent sum of $75 a week to do the station’s weekend all-night show. For months I’d read voraciously about Canada. I learned about the pros and cons of parliamentary government and went to work on my French, after risking near death on-air by pronouncing the last name of Montreal hockey player Rocket Richard like Richard Dreyfus pronounces his first name.

In the fall of 1970 the October Crisis, as it was called, rocked Canada to its bicultural roots, beginning with the kidnapping of a British trade officer, the murder of a provincial cabinet minister and the eventual exile to Cuba of the Quebec separatist extremists who had carried out the plot. Martial law was invoked. Tanks rumbled in the streets. Less than a year after arriving in Montreal, during the worst constitutional crisis in Canada’s history, I was promoted to host the mid-morning show on the city’s most-listened-to station.

As the war raged on in Vietnam, I had the eye-opening experience of absorbing the news from the perspective of a not-so-foreign country. As I recall, there was no real debate in Canada over whether the events at My Lai and Kent State were atrocities, just a mixture of anger and sadness over the slide into chaos “the States” were enduring. As far as I was concerned, whatever social contract that existed between myself and the country of my birth had been severed. I had no interest in President Gerald Ford’s offer of amnesty, a bone thrown to the left after Ford granted a full pardon to former president Richard Nixon. I also ignored President Jimmy Carter’s offer of amnesty, although I was able to express my appreciation when I interviewed him in Toronto years later.

In 1975 the Army started to quietly discharge Vietnam-era deserters (a story I’ve never seen told in the U.S. media). I flew down one weekend, turned myself in at Fort Dix, New Jersey, and by Monday morning, discharge in hand, I was no longer a fugitive. The barracks where I and 30 other returnees were billeted had a Coke machine with a sign warning that it didn’t accept Canadian quarters.

There are no verifiable numbers on how many men, women and children left for Canada during the Vietnam era. Some estimates are as high as a hundred thousand, with about half that number returning when they were able. Another 60,000 mostly Vietnamese refugees, the “boat people,” were given sanctuary in Canada after the war.

The first 30 years of my 45-year career in broadcasting were spent in commercial radio. I did good work, but there was always the sense that the real goal was selling listeners to advertisers. So in 1995, when I was invited by the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. to host Metro Morning, its daily commercial-free current affairs show, I was thrilled. By the time I retired 15 years later, it had, for the first time in its history, become the most-listened-to morning show in the city.

Meanwhile, my only academic credential is an honorary doctorate from Toronto’s York University. At Dartmouth I’d botched my comprehensive exams so badly that I never earned a degree. I got caught up in my career and never did collect my A.B., but framed and hanging where it might otherwise be is my Order of Canada, the highest civilian honor this country awards. I treasure it as an affirmation of Robert Frost’s definition of home as “the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.”

Mary went on to get a master’s and a Ph.D., capping a brilliant career as the director of the school of continuing studies at the University of Toronto. She died of lung cancer in 2009. Our daughter, born in 1976, was recruited to a wonderful job in the States 10 years ago. She has a master’s and doctorate of her own.

She and her son have dual citizenship, just in case.

Andy Barrie retired in 2010. He lives in Creemore, Ontario.