Keith Alexander was driving home after finishing his shift as a computer technician—one of three jobs the Caribbean immigrant held down—when he noticed a garage sale at a handsome house in White Plains, New York. Four years earlier he’d moved his family from Trinidad to the Bronx in New York City, and he was looking for something both “enriching and fun” for his eldest child. The wife of New York Mets ballplayer Tim Teufel owned the property, as it turned out, and she was eager to sell her son’s saxophone, which had rarely been used. Alexander paid $15 for the instrument and took it home to his 12-year-old son Stephon.

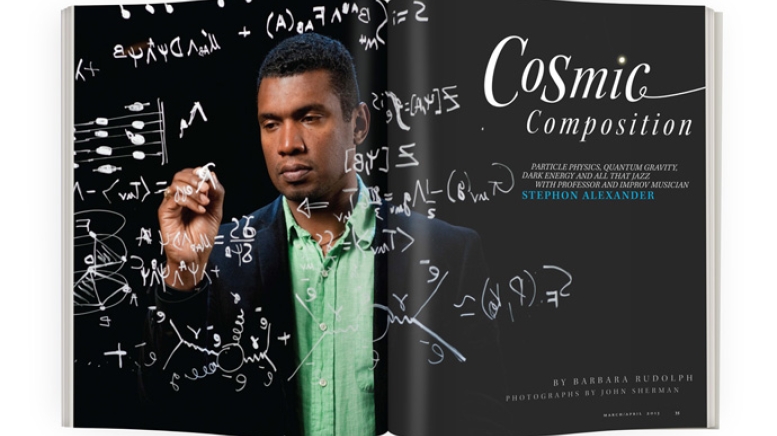

That “chance event” in 1984, recalls Stephon, the Ernest Everett Just 1907 Professor of Natural Sciences, sparked one of his two great passions: music. Now in the early days of his Dartmouth career, as Alexander pursues his research in theoretical cosmology—his second great passion—and plays gigs on tenor saxophone, an openness to improvisation lies at the heart of everything he does, including the new course he’s developed and a new album he’s working on.

“In music it’s important to practice and refine your technique. But when you get up to play you have to throw it all away,” says Alexander. Similarly, in physics research, “You learn the techniques, you master the math, but then there is a willful putting it all away,” he adds.

Alexander aims to explore the connection between quantum physics and jazz improvisation with a popular science book he’s writing. The subject is sure to come up in the undergraduate course, “The Music of Physics,” that Alexander will begin teaching this spring. It will be aimed at both non-science and science majors. “There will be very little math. Musicians Arto Lindsay and David Amram will come to talk,” Alexander says. The theoretical physicist first met Lindsay at a 2001 London dinner party that was hosted by musician-producer Brian Eno.

As the E.E. Just faculty chair, Alexander takes the helm of the E.E. Just Program, which, according to its website, seeks to engender a greater awareness and scientific excellence for students “with an emphasis on underrepresented groups in the sciences.” The chair and program are named after one of the College’s earliest African-American alumni, who graduated in 1907 and became a pioneering cellular biologist.

“The Just program is one of the big reasons I came to Dartmouth,” Alexander says. “I believe that with the right structures put in place I can help underrepresented students see Dartmouth as a home, where they can flourish into scientists while being themselves.”

Across three days in late September an energetic Alexander led the E.E. Just Symposium, which brought to Hanover distinguished physicists and astronomers to discuss their scholarly work and interests. The conference opened with a keynote speech by string theorist S. Jim Gates Jr., the John S. Toll Professor of Physics at the University of Maryland since 1998, a 2013 National Medal of Science recipient and one of the first African Americans to hold an endowed chair in physics at a major U.S. research university.

Alexander’s own research focuses on the interface between cosmology, elementary particle physics and quantum gravity. He wrestles with a profound question: “What is behind the cosmic composition?”

“[We ask] how the world of particle physics and quantum gravity effects can be tested using measurements in cosmology,” Alexander says. “We know there is dark energy and dark matter out there, but we want to know what their identity is and what fundamental physics says about that.”

Born in Trinidad in 1971, Alexander was 8 years old when the family—he has five brothers and one sister—moved to the Bronx. Three years later, his new saxophone in hand, he began playing in his middle school jazz band. Paul Piteo, a New York jazz musician who taught middle school and played gigs at night, led the class. “Paul told us all these stories,” Alexander recalls. “He’d say, ‘There are three things I hate the most—a lazy bum, a junkie and a liar.’

“I had a room in the attic of our house and at night I was able to dial around all the radio stations, and you know when you do this there’s all this static noise. Well, what happened was, what I thought was static noise was actually the music of Ornette Coleman. I got stuck on it. What is this sound?” (As an adult Alexander got to know Coleman—and take lessons from the jazz giant—through his friend Jaron Lanier, a computer scientist and virtual reality pioneer.)

In high school Alexander’s love of music deepened even as he was awakened to a new world: physics. His 10th-grade science teacher at DeWitt Clinton High School, Daniel Kaplan, opened the door to this new terrain. “There was always a presumption from Mr. Kaplan that you were smart,” Alexander recalls. “He talked as if his class were comprised of other physicists. His understanding of physics was so deep and he had this ability to engage and create a climate where you felt it’s okay to make a mistake and transform that mistake into the correct answer.”

Alexander attended Haverford College, majored in physics with a minor in sociology and graduated in 1993. He entered a physics Ph.D. program at Brown University, but after three years he had doubts about his life choice.

He took a leave from Brown and signed on to work as a biophysicist to research atomic scale virus structure determination at Harvard Medical School. After a year Alexander realized he did want to be a theoretical physicist, so he returned to Brown to work with cosmologist Robert Brandenberger.

“I had felt an urgency to use my science to make a difference in the world, and felt that theoretical physics was too abstract and removed from the problems facing society,” says Alexander. “I didn’t want to leave science.” He came to understand that applying his physics background to virus research could have an impact in HIV research. “During my time in the Harvard biophysics department I also learned how much the problems in biology and medicine are dependent on advances in fundamental physics,” he adds.

After earning a Ph.D. at Brown in 2000, Alexander conducted postdoctoral work at Imperial College, London, and the Stanford University Linear Accelerator Center.

In 2005 Alexander joined the faculty at Penn State University, which was “very big, very graduate student-oriented in terms of research,” he recalls. Three years later, “to answer my need to be more involved with undergraduate teaching, I went to the other extreme,” he says, by accepting a position at Haverford. “Then I realized I missed the kind of research I do, which is highly theoretical and requires advanced mathematics. I realized I wanted to have more balance and also be at a place where teaching was a top priority. Dartmouth met that uniquely.”

Dartmouth had contacted Alexander not long after Marcelo Gleiser, Dartmouth professor of physics and astronomy and the Appleton Professor of Natural Philosophy, met Alexander at the annual Isaac Asimov Memorial Debate, held in March 2011 at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Six physicists, including Gates and Gleiser, were invited by astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the museum’s Hayden Planetarium, to conduct the debate.

“We discussed the status of string theory and theories of everything in general,” recalls Gleiser. “It was a wonderful night, with some 2,000 people in the audience. Afterward Neil invited us to his office to drink some very nice wine. Stephon, a good friend of Neil and Jim Gates, was there.”

Gleiser realized that Alexander would be an ideal candidate both to join the physics department and serve as the E.E. Just chair. That night Gleiser asked Alexander if he might be interested in coming.

In March 2012 the College announced Alexander’s appointment. “Alexander’s work is outstanding, and it fits nicely with the other physicists in the department. He brings passion to his research, to teaching and in particular to student mentoring,” says David Kotz ’86, the Champion International Professor in the department of computer science and associate dean of the faculty for the sciences.

Alexander’s former students echo that praise. “He has been incredibly committed to my success as a student and a physicist,” says Garrett Vanacore, who studied with Alexander at Haverford and is now working on a dissertation on condensed matter physics at the University of Illinois. “He has been an exceptional mentor,” adds Martin Blood-Forsythe, who was Alexander’s thesis student at Haverford and is now a physics Ph.D. candidate at Harvard.

As a mentor and a teacher Alexander is both supportive and rigorous. “I’m exploratory, informal—and demanding. I have high expectations,” Alexander says. He always looks for new possibilities—the improvisational instinct at work. “He loves to make connections among people, ideas and disciplines,” says Nicole Yunger Halpern ’11, a physics major and co-valedictorian of her class. Although Alexander arrived on campus after Halpern graduated, she reached out to him and he was “happy to talk,” she says. He’s now advising Halpern, who serves on the alumni advisory board of the physics department, as she applies to graduate programs.

Theoretical physicists have many talents, but the ability to discuss their research with civilians is not always one of them. Explaining his work to someone with no background in physics, Alexander speaks in plain English, often drawing on musical metaphors. “All matter we know to exist in the universe in its past state was a form of radiation energy that was itself vibrating. As the universe evolved from that more simple vibrational state, those wave patterns had to organize themselves into an orchestra of planets, galaxies, solar systems and stars,” he says. “So a big part of the research in cosmology, my field, is to understand what is behind that composition, call it the cosmic composition or the cosmic orchestra.”

For his contributions to theoretical cosmology, Alexander received the 2013 Edward A. Bouchet Award from the American Physical Society in November. The organization cited, in addition to his research, his work in “communicating many ideas of this field to the scientific community and the public.”

Going forward, Alexander’s work will be informed by what he calls “the major discovery” of the Higgs boson, also called the Higgs particle. Part of the Higgs field, which permeates the entire universe, the Higgs boson is invisible to the human eye and is believed to endow all elementary subatomic particles with mass.

“About 85 percent of matter in the universe is unknown—what we call dark matter,” Alexander explains. “About 75 percent of energy is dark energy. We don’t know what it is, but we know it exists.

“A question we ask is, ‘What is the role of the Higgs field with regard to the dark energy problem?’ It will be amazing to see if this major discovery of the Higgs field and the discovery of dark energy speak to each other—and what type of new physics emerges.”

Taking periodic breaks from his physics research and teaching, Alexander is working with 22-year-old New York musician Erin Rioux on an album that will mix electronic and psychedelic dance music with traditional jazz, reggae and spoken word. On one cut, “Stephon explains the creation of the universe in three minutes,” Rioux says.

The two men met one afternoon in the summer of 2012 at the Variety Café in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Noticing that Rioux was working with music software on his laptop, Alexander struck up a conversation. The connection was immediate. “Stephon is a super-awake person who will say ‘Hello’ to anyone he thinks may be interesting,” Rioux says.

After about an hour of increasingly animated discussion, they left the café, stopped off at a nearby apartment Alexander was subletting, grabbed a sax and headed back to Rioux’s in-home music studio. “He started playing his sax and just tearing it up,” Rioux recalls. “At one point he said, ‘Let me get on a mike, I want to do something prophetic.’ ”

Alexander says much of the album is based on concepts in modern physics. That begins with the opening track, “Inside the Mirror,” which Alexander wrote. “Think about a mirror,” Alexander says. “You understand it from the perspective of being outside the mirror and looking at the mirror. But what’s going on inside the mirror? It’s also a metaphor for the mind.”

Then the theoretical physicist changes chords. “It’s a funky house song with jazz saxophone,” Alexander says.

On campus Alexander is still getting to know what defines a Dartmouth student. “They’re independent,” he says. “And they follow through on things. Maybe not immediately,” Alexander says with a laugh, “but they definitely follow through. One more quality—I guess it’s not surprising—but the level of school spirit stands out as unique to Dartmouth as an institution. Students refer to this as home.”

Of course it’s Alexander’s home now, too, and the ever-curious physicist-cum-saxophonist is happily busy, teaching undergraduates at Wilder Hall, tackling deep questions of cosmology—and blowing his horn.

Barbara Rudolph has been a writer and editor at Time and Forbes and is the author of Disconnected, a 1998 book about downsizing, work and identity at AT&T.