Dead on Arrival

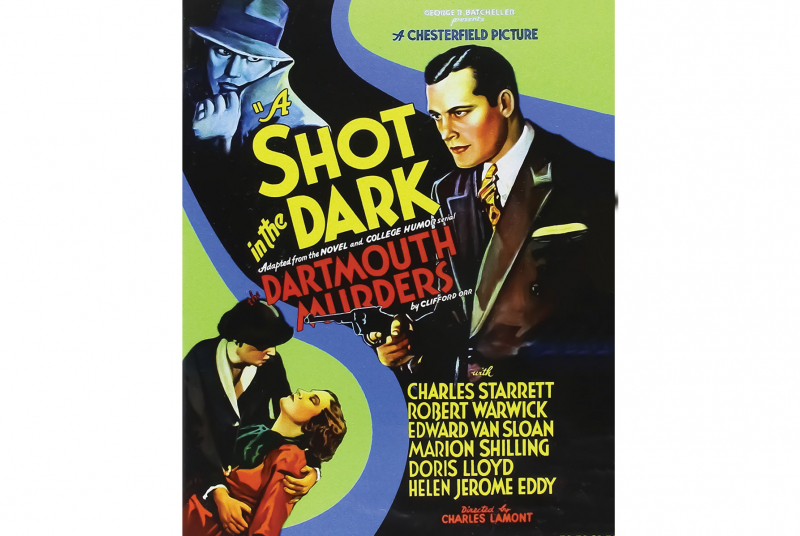

In February 1935, Chesterfield Productions released A Shot in the Dark, a 69-minute film shot at Universal Studios in Hollywood and directed by Charles Lamont (later of Abbott and Costello fame). The black-and-white feature starred famed actors Edward Van Sloan—from the 1931 Dracula—and Robert Warwick, the matinee idol who, three weeks after A Shot in the Dark premiered, appeared in The Little Colonel with Hattie McDaniel, Shirley Temple, and Lionel Barrymore.

A Shot in the Dark bombed. The audio and lighting were poor. The New York Times pummeled the film, noting that it had “an inability to be properly mysterious” and that it was “excessively routine.”

Andre Sennwald, the Times critic, issued a litany of complaints. The film “telegraphs its punches,” “contains enough corpses to populate an honest motion-picture abattoir,” and “in general there is a decided absence of liveliness both in the writing and the playing.” Sennwald concluded his piece with a deeply regrettable turn of phrase, saying that the leads, Charles Starrett and Marion Shilling, “subscribe to the wooden Indian school of acting.”

Starrett was a member of the class of 1926. He had played fullback on Dartmouth’s 1925 national championship football team, and his collegiate career inspired one of his earlier films, Touchdown! His acting career actually started when he and a couple of Dartmouth football players were cast the year after they graduated as extras in a silent comedy film, The Quarterback. Despite the scathing review of A Shot in the Dark, Starrett’s acting career survived. He filmed dozens of Westerns and starred in the Durango Kid series.

The Dartmouth connection to A Shot in the Dark runs far deeper than one alum’s lousy performance. Clifford “Kip” Orr, class of 1922, had written The Dartmouth Murders, a popular 1929 novel that was the basis for the film.

The plot was conventional. Three students are murdered in a November week: one in North Mass dormitory, one in Rollins Chapel, and one at an abandoned inn on River Road. The culprit (spoiler alert!) was a music professor. Orr dedicated his book to Franklin McDuffee, class of 1921, who later wrote the words to the song “Dartmouth Undying.”

“All events and all important characters in this story are entirely imaginary,” Orr wrote on the frontispiece of his book, published by Grosset & Dunlap in New York. But he clearly gives more than a nod to a murder that occurred during his sophomore year. In June 1920, a few minutes after a dispute in a North Mass dorm room, Bob Meads, class of 1922, a junior who sold bootlegged whiskey from Canada, fatally shot senior Hank Maroney, class of 1919, in Theta Delt.

It was an indelible event for Orr, an ebullient redhead from Portland, Maine, who lived in North Mass. With only 1,000 students on the small campus, Orr undoubtedly knew Meads and Maroney—prominent students who had returned to Dartmouth after fighting in World War I.

Orr set much of his novel in North Mass and captured the atmosphere of the stunned college campus. The book describes a flood of newspaper reporters and photographers descending on the campus and quotes one journalist as saying: “It was incredible. Why, college men don’t kill each other. They don’t even fight, seriously. And they don’t have enemies. Not real, deadly enemies.”

At college, Orr wrote plays for the Dartmouth Players and became the troupe’s president his senior year. He also edited The Bema, a monthly literary magazine.

For his first job out of college, he worked at the Boston Evening Transcript as a book reviewer and literary columnist. He then moved to New York City to work in public relations for Robert McBride publishing house but left after six months. “I was rotten at the job,” he said. When he was managing the Wall Street branch of Doubleday, Doran’s bookstore, he wrote The Dartmouth Murders. College Humor magazine serialized it in its September, October, and November 1929 issues with gorgeous illustrations by Benton H. Clark, a well-known artist who worked for The Saturday Evening Post for decades.

By the time the movie came out, Orr was an established literary man. He had joined the editorial staff at The New Yorker and in 1932 released his second novel, another detective tale, The Wailing Rock Murders, to good reviews. In two decades at The New Yorker, Orr wrote more than 400 “Talk of the Town” pieces and editorials, as well as many humorous sketches (“The Death of Santa Claus” among them) and short fiction, including his September 1933 satirical piece, “Savage Homecoming,” which was widely anthologized. He also contributed to radio shows and wrote popular songs, including the lyrics to “Same Old Moon,” “Builders of Dreams,” and “The Polka Dot” for a popular 1929 revue.

In June 1951 Orr left New York and retreated to a nursing home in Hanover, where he died four months later. He was 51.