Campbell’s Coup

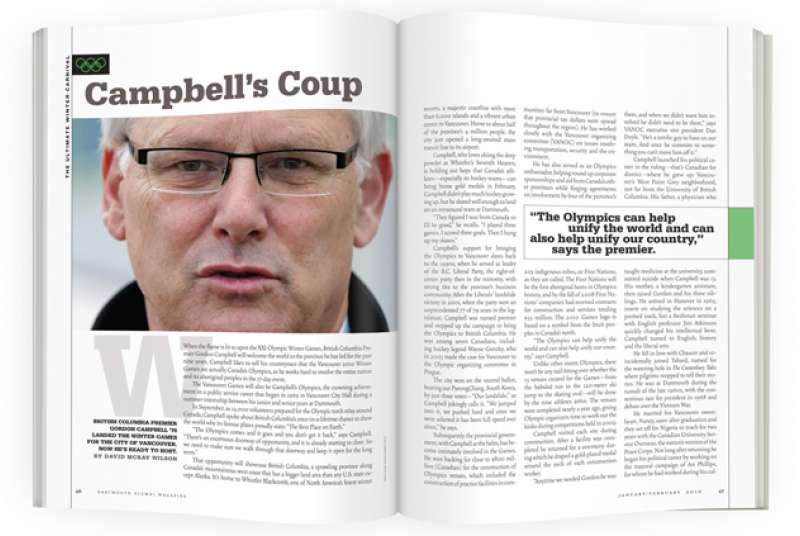

When the flame is lit to open the XXI Olympic Winter Games, British Columbia Premier Gordon Campbell will welcome the world to the province he has led for the past nine years. Campbell likes to tell his countrymen that the Vancouver 2010 Winter Games are actually Canada’s Olympics, as he works hard to involve the entire nation and its aboriginal peoples in the 17-day event.

The Vancouver Games will also be Campbell’s Olympics, the crowning achievement in a public service career that began in 1969 in Vancouver City Hall during a summer internship between his junior and senior years at Dartmouth.

In September, as 12,000 volunteers prepared for the Olympic torch relay around Canada, Campbell spoke about British Columbia’s once-in-a-lifetime chance to show the world why its license plates proudly state: “The Best Place on Earth.”

“The Olympics comes and it goes and you don’t get it back,” says Campbell. “There’s an enormous doorway of opportunity, and it is already starting to close. So we need to make sure we walk through that doorway and keep it open for the long term.”

That opportunity will showcase British Columbia, a sprawling province along Canada’s mountainous west coast that has a bigger land area than any U.S. state except Alaska. It’s home to Whistler Blackcomb, one of North America’s finest winter resorts, a majestic coastline with more than 6,000 islands and a vibrant urban center in Vancouver. Home to about half of the province’s 4 million people, the city just opened a long-awaited mass transit line to its airport.

Campbell, who loves skiing the deep powder at Whistler’s Seventh Heaven, is holding out hope that Canada’s athletes—especially its hockey teams—can bring home gold medals in February. Campbell didn’t play much hockey growing up, but he skated well enough to land on an intramural team at Dartmouth.

“They figured I was from Canada so I’d be good,” he recalls. “I played three games. I scored three goals. Then I hung up my skates.”

Campbell’s support for bringing the Olympics to Vancouver dates back to the 1990s, when he served as leader of the B.C. Liberal Party, the right-of-center party then in the minority, with strong ties to the province’s business community. After the Liberals’ landslide victory in 2001, when the party won an unprecedented 77 of 79 seats in the legislature, Campbell was named premier and stepped up the campaign to bring the Olympics to British Columbia. He was among seven Canadians, including hockey legend Wayne Gretzky, who in 2003 made the case for Vancouver to the Olympic organizing committee in Prague.

The city won on the second ballot, beating out PyeongChang, South Korea, by just three votes—“Our landslide,” as Campbell jokingly calls it. “We jumped into it, we pushed hard and once we were selected it has been full speed ever since,” he says.

Subsequently the provincial government, with Campbell at the helm, has become intimately involved in the Games. He won backing for close to $800 million (Canadian) for the construction of Olympics venues, which included the construction of practice facilities in communities far from Vancouver (to ensure that provincial tax dollars were spread throughout the region). He has worked closely with the Vancouver organizing committee (VANOC) on issues involving transportation, security and the environment.

He has also served as an Olympics ambassador, helping round up corporate sponsorships and aid from Canada’s other provinces while forging agreements on involvement by four of the province’s 203 indigenous tribes, or First Nations, as they are called. The First Nations will be the first aboriginal hosts in Olympics history, and by the fall of 2008 First Nations’ companies had received contracts for construction and services totaling $53 million. The 2010 Games logo is based on a symbol from the Inuit peoples in Canada’s north.

“The Olympics can help unify the world and can also help unify our country,” says Campbell.

Unlike other recent Olympics, there won’t be any nail-biting over whether the 15 venues created for the Games—from the bobsled run to the 120-meter ski jump to the skating oval—will be done by the time athletes arrive. The venues were completed nearly a year ago, giving Olympic organizers time to work out the kinks during competitions held in 2009.

Campbell visited each site during construction. After a facility was completed he returned for a ceremony during which he draped a gold-plated medal around the neck of each construction worker.

“Anytime we needed Gordon he was there, and when we didn’t want him involved he didn’t need to be there,” says VANOC executive vice president Dan Doyle. “He’s a terrific guy to have on our team. And once he commits to something you can’t move him off it.”

Campbell launched his political career in the riding—that’s Canadian for district—where he grew up: Vancouver’s West Point Grey neighborhood, not far from the University of British Columbia. His father, a physician who taught medicine at the university, committed suicide when Campbell was 13. His mother, a kindergarten assistant, then raised Gordon and his three siblings. He arrived in Hanover in 1965, intent on studying the sciences on a premed track, but a freshman seminar with English professor Jim Atkinson quickly changed his intellectual bent. Campbell turned to English, history and the liberal arts.

He fell in love with Chaucer and coincidentally joined Tabard, named for the watering hole in The Canterbury Tales where pilgrims stopped to tell their stories. He was at Dartmouth during the tumult of the late 1960s, with the contentious race for president in 1968 and debate over the Vietnam War.

He married his Vancouver sweetheart, Nancy, soon after graduation and they set off for Nigeria to teach for two years with the Canadian University Service Overseas, the nation’s version of the Peace Corps. Not long after returning he began his political career by working on the mayoral campaign of Art Phillips, for whom he had worked during his college internship.

Today, Campbell, 62, known as “Gord” among friends, sports a shock of snow-white hair combed to the side and dark-framed glasses and often appears without a tie. He enjoys getting out in public and doesn’t shy away from dressing up—or down—for the occasion. To kick off a school hockey tournament he’ll come dressed in a Vancouver Canucks jersey. To promote cancer research he’ll don his cycling togs, bike cleats and helmet to ride alongside Lance Armstrong.

He finds respite from the pressures of public service at his summer cottage at Half Moon Bay, nestled on the coastline about 60 miles north of Vancouver. There he has been spotted in his Dartmouth sweatshirt and cap, paddling along the coast where seals sun themselves along the rocky shores.

“Up there he’ll let his hair down and be completely relaxed,” says Jim Moodie, a longtime friend. “He has two personas—Gordon, the premier who is very driven and very professional, and Gord, who likes to paddle around with a group of friends for an hour or two.”

On the public stage he’s known as a decisive leader who often delivers speeches without notes, encourages lively debate behind closed doors among cabinet ministers with differing opinions, and has won legislative approval for North America’s first carbon tax in 2008. The tax, set at $10 per metric ton and scheduled to rise $5 per year to $30 in 2012, is designed to cut the use of fossil fuels and address concerns about global warming. It should help reduce carbon emissions in Canada by a third by 2020, according to the British Columbia Ministry of Finance.

“Every once in a while you’ve got to ask: What’s the best thing to do? and then get on with it and take the consequences,” says Campbell, who won his third term as premier in May, when his party won a majority of 11 seats. “If you don’t believe in what you stand for there’s no reason anyone should back you up.”

After the election he pushed through legislation that combined the federal goods and services tax with the provincial sales tax to create a 12 percent sales tax in the province. The new tax, which will save businesses up to $2 billion and improve the province’s international trade, spurred thousands of B.C. residents to 20 protest rallies, where they demanded that Campbell’s Liberal Party change its position.

“There is a natural tendency in public life to postpone the difficult decisions, but Gordon has never done that,” says B.C. Attorney General Michael de Jong, a longtime Campbell friend. “He is someone who is drawn to difficult decisions and he has a passion for engaging people on these issues.”

When February arrives in 2010, more unforeseen difficult decisions are certain to arise as the world’s eyes settle on British Columbia—and Campbell.

“This will be the first time I give a speech to 3 billion people,” he says, noting the anticipated worldwide audience for the opening ceremonies. “The Olympics spawns hope in people. It has created such an opportunity for us, and it’s important for us to build on that.”

David McKay Wilson, a New York-based freelance journalist, has contributed to DAM since 2004.