In preparation for his beloved annual spring canoe trip to northern Minnesota, all winter long Steve Posniak could be seen walking through the alleys of his Washington, D.C., neighborhood carrying 50-pound weights. As a stocky man in his 60s, Posniak wanted to be sure he was strong enough to portage alone, carrying gear on his back and a canoe overhead across miles of trails that connect more than a thousand lakes sprinkled throughout the Superior National Forest. The Boundary Waters Canoe Area “offers freedom to those who wish to pursue an experience of expansive solitude, challenge and personal integration with nature,” according to the National Forest Service website. Get away from it all, then keep heading north.

Posniak sought that solitude. He made the trip to the Boundary Waters nearly every year for 25 years, usually in early May to get to the already remote wilderness hugging the Canadian border ahead of the tourist season, so it would be mostly moose traipsing the trails. On one of his first canoeing trips to the region he awoke one morning to the sound of loud throat clearing outside his tent. Disappointed that another camper had encroached upon his quietude, he stepped out to discover a large bull moose standing there. “I go right after the ice melts but before the flies and fishermen come out, so I can share it with the moose and the loons,” Posniak once explained. Some years he went so early that snow would be on his tent when he woke in the morning. Sometimes thin slabs of ice floated on the lakes as his canoe slipped through the pristine waters.

Although she also loves the outdoors, Posniak’s wife, Jane Comings, never joined him for the canoe trips. The lack of hot water and camping on cold ground had little appeal for the now-retired preschool teacher, and she didn’t want her inevitable complaints to diminish her husband’s experience. One year Posniak convinced his then-13-year-old daughter Beth to accompany him. “It rained the whole time, so she sat in the tent and read lots of books,” recalls Jane with a chuckle. “But afterward her reward was to go to the Mall of America. That would be more like a punishment for me or Steve.”

For Posniak’s 2007 trip the retiree arranged to rent gear and obtain his forest permit through Tuscarora Outfitters, as he did every year. He set out on a five-day, four-night journey that extended several miles along Gunflint Trail and Ham Lake. Each evening Posniak camped at a reserved, bare-bones site after a day of paddling along serene waterways surrounded by pine trees and portaging with his pack and 40-pound canoe along forest trails measured in canoe lengths.

On the third morning of his trip, Saturday, May 5, strong winds greeted Posniak when he awoke—winds that would forever change his life. He pulled on his faded-green Dartmouth sweatshirt and built a campfire. Although the region was experiencing extreme drought conditions that spring, and 30-mph gusts were forecast, the U.S. Forest Service had not issued a ban on campfires. A pair of canoeists paddled past his site and waved but didn’t stop to speak as they struggled to make headway against the unusually strong winds.

Exactly what happened next in Posniak’s camp is unclear. Did a burning scrap of paper or leaf from his campfire float up into the parched treetops? Did a last spark from doused embers blow off and ignite nearby bone-dry underbrush? Somehow, flames may have escaped from his fire ring and, triggered by the wind, ignited the nearby brush. What is known is that Posniak discovered a large fire burning behind his campsite. He began a desperate attempt to extinguish it, using a small cooking pot to carry water, but the fire spread quickly to nearby brush. Smoke soon filled the air and flames reached higher branches, which crackled and fell to the forest floor, igniting more debris. Hot gusts blew in from the southeast and the fire began to race across the dry treetops.

Posniak continued dousing the area but began to lose hope as it became clear the fire was beyond control. Distraught, he realized he had to leave.

Posniak packed his belongings, heaved the canoe upside down overhead and rested the yoke on his shoulders. Carefully and slowly making his way through smoke and falling ash, with flames on either side of the trail, Posniak spent several fearful hours portaging and then paddling out of the roaring destruction. (On a normal day he was about a 90-minute journey from the outfitters.) With high winds pressing against him, the physical effort of canoeing out proved painfully difficult, but at last he returned, exhausted and disheartened, to the site of the outfitters under a reddening sky.

With firefighting efforts in the area well under way, everyone present was ordered to evacuate the property. The owners rushed to load up expensive Kevlar canoes and personal items. As Posniak spread out his equipment on a picnic table to repack, the county deputy sheriff approached him. The deputy was trying to account for all campers in the area. He interviewed Posniak and several other people about what they had seen and where they had camped. Surrounded by the commotion of firefighters working along the burning perimeter of the outfitter’s property, Posniak was detained at the picnic pavilion for a second questioning by two U.S. Forest Service officers. When he was asked where he had camped the previous night, Posniak gave incorrect information, stating he had camped at Cross Bay Lake and had come upon a fire already burning out of control at a Ham Lake campsite. The officers requested that he surrender his camping permit and asked to take his photo. When the camera failed, Posniak agreed to meet them the following day for the photo and gave them the address of his motel.

Posniak removed a layer of ash from his car, gathered his belongings and drove to the motel for a fitful night’s sleep. The next morning he was met by the two officers and read his Miranda rights, at which time, now under oath and perhaps a little more rested, he said that indeed he had camped at Ham Lake the night before the fire. He was allowed to return home to Washington. Later he would learn that he had been identified by the two canoeists who spotted him at the site where it was believed the fire had originated; they had described him as a “portly man in his 50s wearing a Dartmouth sweatshirt.” (His wife, Jane, imagines he was flattered by people thinking he was a decade younger than he was.)

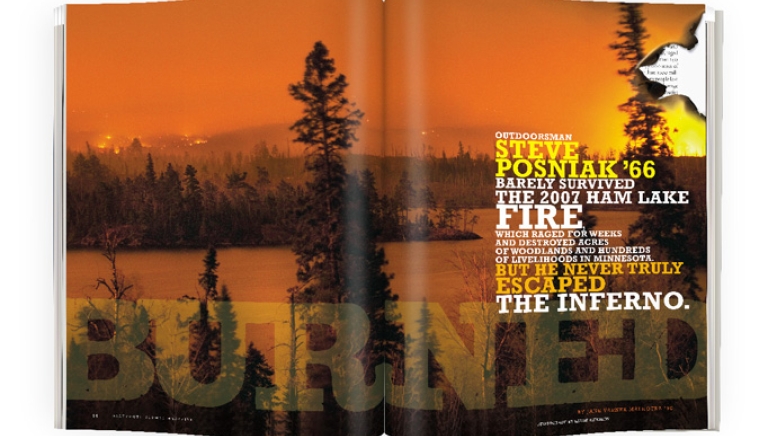

The blaze, which became known as the Ham Lake Fire, raged for two weeks and crossed the Canadian border. More than 140 structures in Minnesota were destroyed, as were 75,000 acres of woodlands. Reports estimated damages at more than $100 million. Firefighting costs alone totaled $11 million. Many people lost homes, others their livelihoods. The charred scenery and damage to outfitters’ buildings and equipment hit the summer tourist season hard. Although no one was killed, the Ham Lake Fire was devastating for the Boundary Waters. And though he made it to safety, it was even more devastating to Posniak, who, it turns out, would never truly escape the inferno.

As a young boy growing up in a quiet Washington, D.C., neighborhood, Posniak sought connection with the outdoors wherever he could find it. Active in the Boy Scouts, he enjoyed camping and hiking in the Appalachians or near his home in Rock Creek Park, and he biked alone on the C&O Canal towpath 60 miles to Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, in his early teens. He ran cross-country at Wilson High School and Dartmouth, where he also became active in the Outing Club.

Posniak became politically active at a young age. At All Souls Unitarian Church in downtown D.C. he participated in the choral group and served as president of the youth group, leading pickets of segregated department stores in the area. He grew close to his mentor, Jim Reeb, assistant minister at All Souls. Reeb’s murder in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 deepened Posniak’s commitment to civil rights work. In college Posniak joined the political action committee of the Dartmouth Christian Union. The summer after his freshman year he served as a marshal in the 1963 March on Washington. After graduating with a degree in government he participated in Upward Bound at Talladega College and helped register Alabama voters.

Bob Burka ’67, who attended middle and high school with Posniak before the two attended Dartmouth, remembers him as a thoughtful young man, deeply concerned about the political issues of the time, including civil rights, the buildup to the Vietnam War and home rule for the District of Columbia. Steve’s younger brother, John, describes the teenage Steve as a loner, always hardworking and writing for teen magazines to earn money—and as an athlete dedicated to cross-country and canoeing. In college he also developed a love of snowshoeing. “And Steve was eccentric, a little counterculture,” adds John, smiling.

Graduate school in public administration brought Posniak to the University of Minnesota in 1966. He then taught political science at Carthage College in Wisconsin for four years, where he met Jane, a French professor from Oberlin, Ohio. They moved to Washington, married, and had their daughter Beth in 1979. “Steve was always a very involved and loving father,” recalls Jane fondly. “Maybe a little disappointed when she chose Oberlin over Dartmouth.” During his career he worked in various jobs with the federal government, including 20 years in the information technology division of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), before he retired in 2006.

Posniak first discovered the Boundary Waters in the late 1980s, when EEOC colleagues from Minnesota encouraged him to take a trip there. Although Jane, Steve and Beth made regular trips to visit family in Michigan, where they enjoyed canoeing and hiking together, spring in the Boundary Waters soon became Steve’s special escape and the highlight of his year.

On a few occasions Posniak went to the Boundary Waters with friends. “He often asked me to join him on the trip,” says Chuck Sherman ’66, who lives in Vermont. “I’m from Minnesota and I’ve been to the Boundary Waters, but I was never able to go with Steve. He usually went solo and never took a fishing rod, just went with a camera, looking for moose.”

Always a quiet guy, in the months after the fire Posniak withdrew even more and, according to Jane, he didn’t sleep much at night. He hadn’t told her about the fire until about two weeks after his return, when he needed to explain the many phone calls from lawyers. News of the blaze was prominent in Minnesota but not in Washington. Posniak kept details of the incident and the ongoing legal issues from both family and friends. Beth, who lived nearby in Virginia, became engaged, and he made plans for a 30th wedding anniversary Elderhostel trip to Wyoming with Jane to learn more about moose. He organized a successful event for the Dartmouth Club of Washington, D.C., featuring an evening with classmate Jim Cason ’66, the retiring U.S. ambassador to Paraguay.

Nearly a year and a half after the fire the United States filed criminal charges against Posniak. On October 20, 2008, he was indicted in federal court in Duluth, Minnesota, on three counts: one felony for willfully setting timber on fire and two misdemeanors for leaving the fire unattended and for giving false information to a forest officer about where he had camped. Although campfires were permitted at the time, trash fires were not, according to rules listed on the back of the permit. Because U.S. Forest Service officers thought Posniak had put paper in his fire, they considered it an illegal trash fire. A guilty verdict would mean up to six years in prison and a $250,000 fine.

Jane recites these charges, sadly shaking her head. “He certainly didn’t deliberately set brush on fire, nor did he abandon it wantonly,” she says. “He stayed as long as he could, trying to put it out.” The final charge, giving false information to a forest officer, seemed particularly unfair in Jane’s eyes. “Although he had misrepresented himself the day before, the next day when they were talking officially on record, he gave the correct information. His lawyer tried to [get the government to] drop that charge, but they wouldn’t, which I believe was somewhat unfair because when he came out he was exhausted and traumatized. I don’t think he was deliberately lying.” She pauses. “He was simply overwhelmed.”

According to news reports and blog postings at the time, reactions in Minnesota to the indictment were mixed, but many were sympathetic. Longtime residents of the area recognized that conditions were ripe for a fire, whether ignited naturally or accidentally. “I’d rather not know who did it. I feel bad for [Posniak], actually,” Jan Sivertson, who lost her home in the fire, told the Duluth News Tribune. “With it as dry as it was, it could have happened to anyone. There was no fire ban on. And for all we know he may have tried to put it out. We’ve all had fires we thought were out that spring back up. It’s not going to help anyone to punish this man any more.”

Posniak made the 20-hour drive from D.C. to Minnesota twice in two months for court appearances in Duluth, working with his lawyer in Minnesota to remove the word “willfully” from the felony charge and to dismiss his initial, incorrect statement. With an aggressive prosecution under way, defense costs were growing, adding stress to an already desperate situation.

On December 15, 2008, as Jane explains, he faced “a double whammy.” That day the federal court in Duluth announced its decision to uphold the felony charge as written, rejecting several motions to have charges reduced and evidence dismissed. The same day, he received a package of paperwork from his lawyer to finalize a lien on Jane’s family cabin in Michigan to secure payment for mounting legal fees. With his trial set to begin in January, he had become uncharacteristically organized. Soon Jane was to discover that he had been doing more than just preparing for his trial. Not only had he paid all their bills through the end of the month, he had also written down for Jane detailed information about everything from their financial picture to his wish to have his body donated to Georgetown University’s medical school.

And then, on December 16, he wrote a note for Jane and duct-taped it to the front door. It warned her to be prepared for a surprise in the back yard when she returned from a work meeting for preschool teachers that evening. When Jane came home and saw the note, she thought perhaps he’d finally trimmed the hedge out back as she’d been asking him to do for months. What she discovered instead left her and Posniak’s friends and family devastated: Posniak had taken his own life with a shotgun she didn’t know he owned. He left another note for the police explaining that he would try to turn the safety back on after using the gun on himself, to minimize danger to others.

“I’m not sure why he did what he did,” Jane says. “At first I thought he was just too distraught about everything that had happened, but looking back, I think he was simply doing it to protect Beth and me.”

More than 200 people attended Posniak’s memorial service at his Unitarian church in Bethesda, Maryland, including childhood friends, EEOC colleagues, neighbors, Jane’s preschool teacher friends, council members from the neighborhood advisory commission on which Posniak had served and Dartmouth alumni. For a man many described as a quirky, private person, he clearly had many devoted friends. A eulogy from Beth recalled childhood memories of building an igloo with her dad, who eventually had to coax her out with the promise of hot chocolate. When she spoke of the igloo that her father had built for himself in those final months, those gathered in his memory cried together. Jane asked that in lieu of flowers, donations be made in Posniak’s name to the Class of 1966 Cabin to honor his love of Dartmouth and the outdoors.

As both a lawyer and his longtime friend and neighbor, Burka wishes he had known about Posniak’s legal woes before he died. “As I’ve done for friends in the past, at least I could have helped explain the legal process to him. And if appropriate I would have sat with him at the trial just to hold his hand—not to take the place of his lawyer, who I have no reason to doubt was perfectly competent. He knew what he was doing,” Burka says. “It was a very over-prosecuted case. And when you deal with the federal bureaucracy in court, they have incredible resources relative to an individual. In many ways Steve was a sophisticated person, but in this setting, with jurors and bailiffs and the weight of the whole federal government coming down on him, it can be overwhelming.”

Minnesota outfitters were also heartbroken by the news of Posniak’s death. Sue Ahrendt, co-owner of Tuscarora Outfitters, told reporters that in the end Posniak became the single casualty of the Ham Lake Fire. Posniak’s attorney, Mark Larsen, vehemently accused the federal government of going too far. “This is something that people in my line of work call overcharging,” Larsen told the Associated Press at the time of Posniak’s death. He said he had planned to introduce evidence of possible alternative sources for the wildfire, and that even if it had originated from Posniak’s campsite, it was not started willfully.

Sherman wonders why Posniak was pursued so aggressively. “The prosecutor ought to be punished for overcharging in this case and putting Steve over the edge,” Sherman says. “He didn’t know his target. I wonder if he ever even met Steve. He was such a gentle, harmless guy.”

In the days following Posniak’s suicide, however, prosecutor William Otteson stood his ground and defended the U.S. attorney’s office. After expressing his sympathy in a call to Larsen, Otteson issued a public statement that Posniak had been “properly charged with a felony and two misdemeanors arising out of admitted conduct,” and added that “his defense counsel’s suggestion that the United States is to blame for his unfortunate outcome is simply unwarranted.”

Four years after the fire, the Boundary Waters boreal forest is regenerating. Part of the natural cycle in the region, fires are needed to reseed native trees such as jack pine, whose seed cones burst open only when exposed to intense heat. Signs of renewal were evident just months after the fire. In July 2008 one enthusiastic naturalist posted a description online of the beautiful deep-green carpet on the forest’s fertile floor, enriched by the ash and nurtured by additional sunlight. Another posted a picture of a bull moose standing in tall, glowing green grass amid a few blackened tree stumps. Although the landscape had changed dramatically, nature’s process of rebirth had begun anew, with hope for a verdant future—one that Steve Posniak would be glad to see.

Jane Varner Malhotra is a freelance writer and editor. She lives with her husband, Amit Malhotra ’90, and four children in Washington, D.C. This is her second story for DAM.