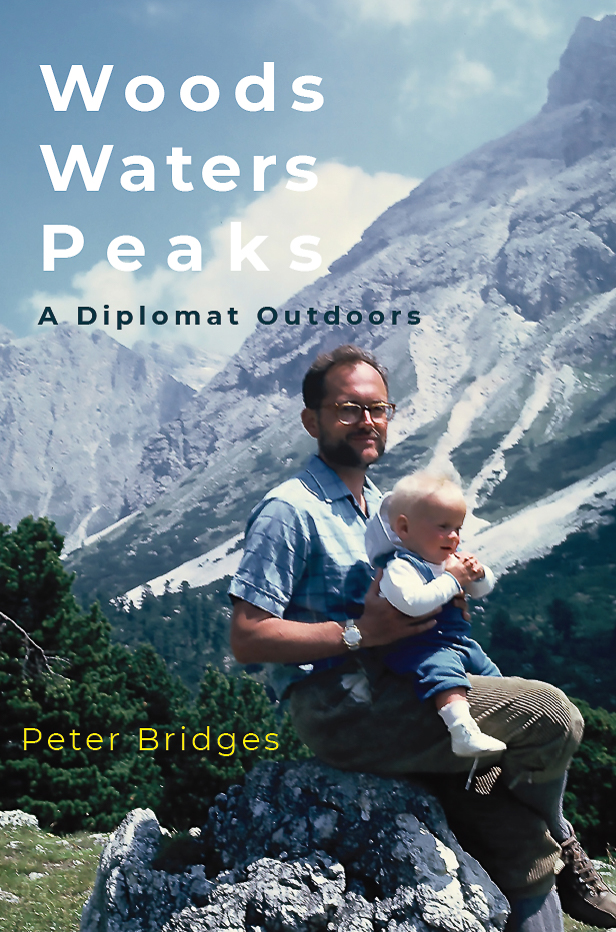

Peter Bridges ’53 has had a busy life. A career U.S. Foreign Service officer, he was posted in Panama, Russia, Czechoslovakia, and Italy before being appointed ambassador to Somalia by President Reagan. In his new memoir, Woods Waters Peaks: A Diplomat Outdoors, Bridges regales readers with tales of his international travels, focusing mostly on his personal, not professional, exploits. (His earlier autobiography, Safirka: An American Envoy, focused on his three decades in the Foreign Service.)

Peter Bridges ’53 has had a busy life. A career U.S. Foreign Service officer, he was posted in Panama, Russia, Czechoslovakia, and Italy before being appointed ambassador to Somalia by President Reagan. In his new memoir, Woods Waters Peaks: A Diplomat Outdoors, Bridges regales readers with tales of his international travels, focusing mostly on his personal, not professional, exploits. (His earlier autobiography, Safirka: An American Envoy, focused on his three decades in the Foreign Service.)

In this new book, he tells readers of his many mountaineering and hiking adventures. He climbed Moosilauke as a freshman and with classmates at their 50th and 60th reunions. In between, he summited the highest peaks in Colorado, New England, Scotland, and the Dolomites. After reaching age 70, he and his wife trekked across Austria, Corsica, Ireland, and Italy. Not one to shy from danger, he climbed Stromboli to watch fire erupt from its crater. He canoed into wilderness in Panama and met a wolf on a ridge in Mongolia.

In this excerpt, Bridges recounts his life in Somalia from 1984 to 1986, including a hike to the top of a forested mountain being ravaged by over-cutting.

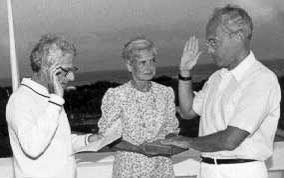

We spent three years in Rome, and then Mr. Reagan sent me as ambassador to Somalia, not a place where any Republican campaign contributor wanted to go. For a career Foreign Service officer to be named an ambassador is, for most of us who make it, a peak, the summit of the career, even if the country of one’s assignment happens to be Somalia, the eighth-poorest country on earth.

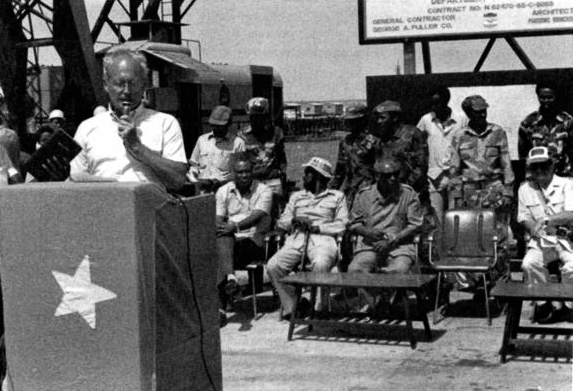

If Somalia was poor, it was large and strategically important, and I was responsible for our largest civilian and military aid program in sub-Saharan Africa, around $100 million a year. It was a difficult job, and I liked it. I had no further ambition, and so I decided no one could hurt me professionally. I carried out my instructions, and the State Department gave me a lot of leeway. I reported the scene as I saw it to Washington, whether or not that was what Washington might want to hear.

I think I had been in Mogadishu six months when I came upon my old volume of Plutarch. The great biographer wrote that when Julius Caesar once passed through some miserable village in the Alps, he remarked that he would rather be first in that village than second in Rome.

I laughed. I was no Caesar, but I had been second—in our embassy—in Rome, and now I was first in our embassy in Mogadishu!

Mogadishu was no miserable Alpine village, though many of its million inhabitants were desperately poor, and Somalia had become a police state. One saving grace was that it was not a totally efficient police state. Besides, there were indications that the country’s longtime dictator Mohamed Siad Barre would soon flee to enjoy the fruits of his corruption elsewhere, perhaps in Europe. A better regime would certainly ensue, or so I thought, as did many other foreigners and my Somali friends. Years later I made clear in my diplomatic memoir Safirka: An American Envoy that no one, Somali or foreigner, foresaw the horrendous civil war that began several years after I left Mogadishu.

I kept up my running in Mogadishu at dawn, the pleasant time called waaberi before the sun heats the capital that is two degrees north of the equator. I ran with my wife (when she was not working in Rome) from our three-bedroom hilltop villa down to the wide nearby beach. I coursed along the western edge of the Indian Ocean, while out at sea the rising sun lit up fine great thunderheads. Sometimes I would encounter my colleague the Soviet ambassador, a pleasant Uzbek, walking along the beach with a bodyguard.

One day when I went running in the dunes behind the beach, a dog began following me. He belonged to an unrecognized, handsome breed of short-haired, sandy-colored, medium-sized Somali dogs that lived in Mogadishu’s streets. Some Somalis, perhaps most of them, thought dogs were unclean creatures, but others liked and fed them. My driver Scerif Ahmed Maio had owned a dog until his neighbors made him get rid of it.

This dog followed me to the gate of our villa, no doubt wanting a handout. I did not give him one, but the next morning he met me again and almost every morning after that. We had a dog, Jethro, but he was in Rome. I thought it would be good to have a canine companion in Mogadishu, and I was tempted to take in this one, but finally I told him “No,” and he went to seek another master.

The Somalis had recently built a slaughterhouse not far up the coast from where I ran, and it discharged its offal into the sea. My predecessors had swum off that beach, but now sharks came. Somali children and adults nevertheless sometimes swam there, and sometimes they were attacked. One evening at a reception the Soviet ambassador asked me, “What would you do if you saw a shark attack somebody one morning?”

“I frankly don’t know,” I replied. “What would you do?”

“I don’t know, either, but I’ve thought about it.”

He had a chance to decide a month later. A shark took a foolish boy who was a few yards out from the beach.

“My comrade and I just stood there,” the ambassador said. “The boy was gone in a few seconds.

“Well, I suspect I would have done the same,” I replied. Fortunately for me, the occasion never arose.

I had an alternate running route that took me several miles along the city’s streets before the great sun rose. I did not worry about security. There were occasionally other non-Somali runners, and none of us wore names on our shirts. Then one morning I turned a corner, and there was a Somali teenager.

“Warhaye, Peter,” he said. I was not exactly unknown, even without a name tag, but I had to keep running.

The official sedan of the American ambassador to Somalia was a handsome blue Oldsmobile. My driver Scerif was an engaging Somali who became my friend. When I went to visit places in the countryside I sat next to Scerif as he drove and conversed with him in my halting Somali. For want of a capable teacher my language skills never got good enough for me to use with officials, who, in any case, were almost always fluent in English or Italian. With one Somali general, who had spent six years in the USSR and hated Russians, I spoke Russian as a sort of mocking joke between us.

Every month or so I would go see the dictatorial president, Mohamed Siad Barre. He lived and worked in a fortified hilltop palace called Villa Somalia. (It had been Villa Italia when colonial governors lived there.) Most often the appointment would be around midnight. Like his fellow dictator Josef Stalin, Siad kept late hours. A few minutes before the scheduled appointment Scerif would fix the two small flags—American and ambassadorial—on the front fenders of the Olds, and we would drive to Villa Somalia, not far from where I lived. The driveway went up a steep incline to the entrance. Scerif took it slow. The guards were armed with AK-47s, and it was hard for him to see the way ahead because they focused searchlights on the car. Siad’s guards came from his immediate clan, the Marehan, and I always thought they looked too young and too trigger-happy.

The president’s office always confirmed my appointment far enough in advance so Scerif could go home for dinner at the end of the regular work day and come back to take me to the president. Late one evening, though, I got a call to see the president right away. Why the urgency, I was not told. Of course I went, but without Scerif. He had no telephone at home and lived too far away for me to get him, if indeed I could have found his house in a part of town that lacked street lights.

I put on a clean shirt, stuck the flags on the Olds, and started off. I still remember driving slowly, slowly, up that incline into the searchlights’ blinding glare, and stopping when someone shouted. The young guards must have known whose vehicle it was—right? They held my car there a long while. Fortunately, they didn’t shoot. The next day I told the minister for the presidency, Abdullahi Addou, I was not going to repeat the experience. I was, I said, always pleased (not really) to see the president but, urgency or not, I needed a little more advance notice.

I traveled widely in Somalia, including its high country. Somalia has a long sea coast backed by arid grasslands almost the size of Texas, but it has highlands, too. I once visited Somalia’s last forest. It was in the nation’s only real mountains, above the Gulf of Aden. I went with my friends Bill and Arlene Fullerton. He was the British ambassador and his Cornell-educated wife was a native of Westchester County, New York. We stood in the cool air under 100-foot-tall pencil cedars atop a rocky escarpment 7,000 feet above sea level, looking down at the coast 10 miles away where the temperature can reach 120 degrees.

Alas, the forest was in the hands of the Somali prison guard corps, which was operating a sawmill there. They were cutting only dead trees, they said. I could see that was not so, and the goats and sheep they were grazing in the forest were devouring all the seedlings. Somalia was well on its way to becoming a thoroughly ravaged country, thanks to humans and their herds, even before the civil war came.

Another day found me 100 miles inland from Mogadishu in a curious landscape. It was a grassy plain many miles wide. Across from it rose great rounded monoliths of pre-Cambrian rock. Buur Eibi, the highest of these, rose 1,000 feet above the plain. At its base was a huge cavern that was the meeting place for the nearby village. A young American archaeologist, Steven Brandt, was methodically excavating the cavern’s floor and had found a dozen ancient skeletons and many artifacts. This cavern had been a meeting place for millennia, since the time when Somalia and the Sahara had both been green grasslands, good pasture for the cattle of old humans.

The archaeology of the place was fascinating, and the climb to the top of Buur Eibi was good, too. There was a little stone chapel on top. The local headman said it was the tomb of a Muslim saint. No doubt it was, but I stood on the summit looking over the great plain, and I could imagine humans standing there many millennia ago, long before Abraham or Christ or Mohamed, honoring gods who they believed brought good rains to what was then a land of milk and honey.

Reprinted with permission of Opus Self-Publishing, Politics and Prose Bookstore from Woods Waters Peaks: A Diplomat Outdoors by Peter Bridges