Eighteen years after becoming the first Dartmouth varsity crew to beat Harvard and win Eastern Sprints in the same year, the 1992 heavyweights were a dark-horse entry at the 2010 Head of the Charles, the world’s largest regatta.

Among the other contenders in the alumni eight men’s event were a talented young crew from Cornell, a Northeastern boat stacked with recent national team rowers from six countries, and a Dartmouth all-star squad that included a 2008 Olympic gold medalist from Canada, four former U.S. national team oarsmen and two Oxford Blue Boat alums.

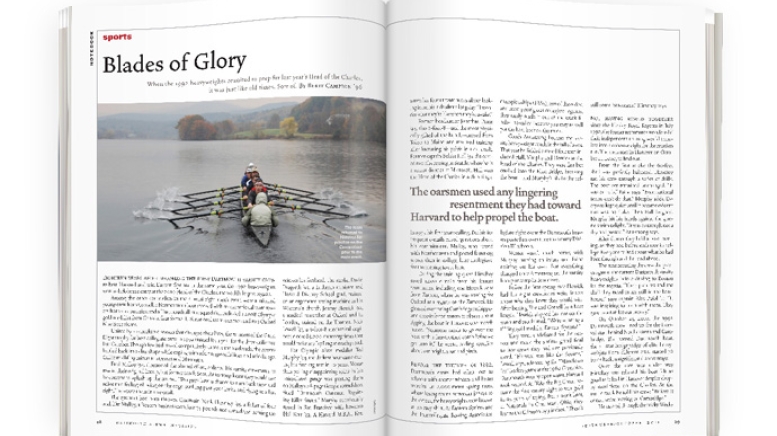

United by a remarkable season that changed their lives, the winners of the Great Eight trophy for best collegiate crew in 1992 trained for a year for the three-mile race last October. Though few had rowed competitively in more than a decade, the rowers battled back into elite shape while coping with adult responsibilities and middle age. Call it midlifing minus mistresses and Maseratis.

Fred Malloy ’94, director of the alumni effort, enlisted his varsity crewmates to row in their original lineup, but former coach Scott Armstrong knew they would not be content to splash up the course. “You guys have a chance to turn back time and relive that feeling of being on the edge, pushing past your limits and flying in a fast eight,” he wrote them in an e-mail.

The gauntlet had been thrown. Coxswain Mark Hirschey ’93, a father of four and, like Malloy, a Boston businessman, lost 35 pounds and considered naming the vein on his forehead. The stroke, David Dragseth ’93, a Lutheran minister and Harvard Divinity School grad, trained on an ergometer rowing machine in his Wisconsin church. Jeremy Howick ’92, a medical researcher at Oxford and in London, trained on the Thames. Nick Lowell ’93, a 6-foot-8 mechanical engineer, clocked 5,000-meter erg times that would make any Ivy League coach proud.

For Olympic silver medalist Ted Murphy ’94, the darkest hour came during his first erg test in 10 years. Worse than pulling disappointing splits in his uninsulated garage was posting them on Malloy’s 28-page Google spreadsheet titled “Dartmouth Oarsmen Regaining Killer Status.” Murphy occasionally rowed in San Francisco with bowman Phil Kerr ’92. A Harvard M.B.A., Kerr wrote his former teammates about looking in on his kids after a long day: “I wonder what they’re like when they’re awake.”

Former headhunter Jonathan Paine ’94, also 6-foot-8—and the most physically gifted of the bunch—moved from Tokyo to Maine and resumed training after fracturing his pelvis in a car crash. Former captain Sohier Hall ’92 dislocated two ribs rowing in Seattle, where he is a senior director at Microsoft. Hall won the Head of the Charles in a club single in 1993, his first year sculling. But his infrequent e-mails raised questions about his commitment. Malloy, who rowed with Northeastern and posted faster erg scores than in college, later apologized for threatening to cut him.

During the training quest Hirschey saved 1,400 e-mails from his former teammates, including one Howick sent from Zambia, where he was rowing for Oxford at a regatta on the Zambezi. He glossed over racing Cambridge on hippo- and croc-infested waters to obsess about rigging the boat in Hanover one month hence. “Someone needs to go over the boat with a fine-toothed comb before we get into it,” he wrote, adding specifics about oar height, span and pitch.

Before the triumph of 1992, Dartmouth crews had often lost to schools with shorter winters and better recruits. In 2,000-meter spring races, where losing teams surrender jerseys to the victors, the heavyweights were known as an easy shirt. At Eastern Sprints and the Intercollegiate Rowing Association championships (IRAs), two of the oldest and most prestigious collegiate regattas, they rarely made it out of the truck finals—so-called because you may as well put the boat back on the truck.

Coach Armstrong became the varsity heavyweight coach in the fall of 1991.That year he fielded a coxed four that included Hall, Murphy and Howick at the Head of the Charles. They were fast but crashed into the Eliot Bridge, breaking the boat—and Murphy’s rib. In the collegiate eight event the Dartmouth heavies posted a slower time than many Division III schools.

Winter wasn’t much better, with Murphy nursing an injury and Paine training on his own. But everything changed once Armstrong set the varsity lineup at camp in Tennessee.

Before the first spring race Howick had his eight crewmates write letters about why they knew they would win. After beating Yale and Cornell by a boat length, Howick slapped his oar on the water and proclaimed, “We’re winning a f***ing gold medal at Eastern Sprints!”

They went undefeated for the season and made the sprints grand final to face crews they had not previously raced. “Harvard was like the Soviets,” Lowell says, referencing the “Miracle on Ice” hockey game at the 1980 Olympics. Dartmouth won by open water. Harvard took second. At IRAs the Big Green became the first varsity eight to win gold in 95 years of trying. But a week later, at Nationals in Cincinnati, Ohio, they lost to the Crimson by 3 inches. “There’s still some bitterness,” Hirschey says.

Not having rowed together since the Henley Royal Regatta in July 1992, the former teammates wondered if their independent training would translate into a cohesive eight for the reunion run. The men met in Hanover on October 21, 2010, to find out.

From the first stroke the 60-foot shell was perfectly balanced. Hirschey ran his crew through a series of drills. The boat set remained unchanged. “It was on rails,” Paine says. “Even national teams can’t do that,” Murphy adds. Everyone kept quiet until it became evident this was no fluke. Then Hall laughed. Murphy hit his hands against the gunnels with delight. “It was as though not a day had passed,” Armstrong says.

After dinner they held a boat meeting, as they had before each race in college. Everyone talked about what he had been through and the road ahead.

The next morning the crew did pieces against the current Dartmouth varsity heavyweights before driving to Boston for the regatta. “Their pictures and the shell they raced in are still in the boathouse,” says captain Alex Pujol ’11. “It was inspiring to train with them. They gave us a run for our money.”

On October 23, 2010, the 1992 Dartmouth crew lined up for the interval start behind Northeastern and Cambridge. The second Dartmouth boat, the all-star hodgepodge of elite heavyweights from different eras, started 36 boats back, a significant disadvantage.

Once the race was under way Hirschey was relieved his boat felt as good as it had in Hanover despite choppy conditions on the Charles. At the 1-mile mark he told his crew: “Believe it or not, we’re moving on Cambridge.”

He steered through the tricky Weeks Footbridge turn near the Harvard campus. The riverbanks were lined with cheering fans from prep schools and universities of every stripe and color. In front of the Newell Boathouse, Hirschey told his oarsmen to use any lingering resentment they had toward Harvard to help propel the boat past the 2-mile mark. On the final turn he called for 20 all-out strokes and, 500 meters from the finish, yelled, “Empty your tanks! No regrets!”

The 1992 varsity heavyweights crossed the line in 15:46, earning an age-adjusted time of 15:35—good enough for second place behind repeat winner Northeastern, a crew that trains together regularly on the Charles.

The Dartmouth all-stars overtook eight crews and posted a time of 15:47. They took third place with their age-adjusted time of 15:43.

That night the two crews met up at John Harvard’s bar in Cambridge to celebrate their double-podium finish. Talk turned to the October 2011 race. “The wives said not for 10 years” Hirschey interjects.

“We leave next year’s race up to the professionals,” says Malloy, referencing the all-star boat organized by Dan Perkins ’97. A four-time U.S. national team oarsman and winner of the prestigious Boat Race for Oxford, Perkins has survived two brain surgeries as well as testicular cancer and lymphoma. “We may make one or two personnel changes to gain speed and an age handicap. Northeastern should be on notice,” he says.

Meanwhile, the 1992 heavyweights haven’t exactly kicked back. Hirschey still gets up at 5:30 a.m. Howick and Hall both row three times a week. Kerr says the experience made him a better husband and father. Dragseth recently did a 50-kilometer cross-country ski race. And Paine just rowed across the Atlantic in 42 days, 17 hours and 52 minutes—and has his sights set on the London 2012 Olympics.

Berit Campion is a freelance writer who lives in Salt Lake City, Utah. At Dartmouth she rowed before joining the cross-country ski team.