While two Olympic medals are the most tangible manifestation of my successful hockey career, my time “in the crease” provided much more than medals to my team, our fans and, in retrospect, to me.

After our team’s success in both the 1998 and 2002 Winter Olympics I had many requests for speaking engagements with various groups—schoolchildren, businesses and charities. Usually the request was for a “motivational” speech. While all true champions combine focus with a strong desire to succeed, the underlying theme of my talks was the need to believe in one’s own potential as fundamental in any endeavor—from physical activities to business challenges to personal relationships.

“How did you get there?” I was often asked. My Grandma T. was a big influence in my life when I was growing up. Gram was stern and old school, and I learned never to say, or even to think, “I can’t.” She repeated and reiterated so often and in so many different ways the idea of believing in yourself that it became an inherent part of my thought process. Success also required hard work. For each sports season, each new round of music lessons and orchestra tryouts, the choice of participation was mine. Once I had decided, my parents’ only condition was that I do it right. I would prepare for each lesson. I would work hard at every practice: soccer, hockey or tennis. I would not miss a workout. I would be one of two players at a practice on Halloween (and unlike the other player, who hated candy, I was a chocoholic!). I would miss my high school prom for a hockey game (though perhaps it could be said I had 19 escorts since I was the only girl on my school’s team).

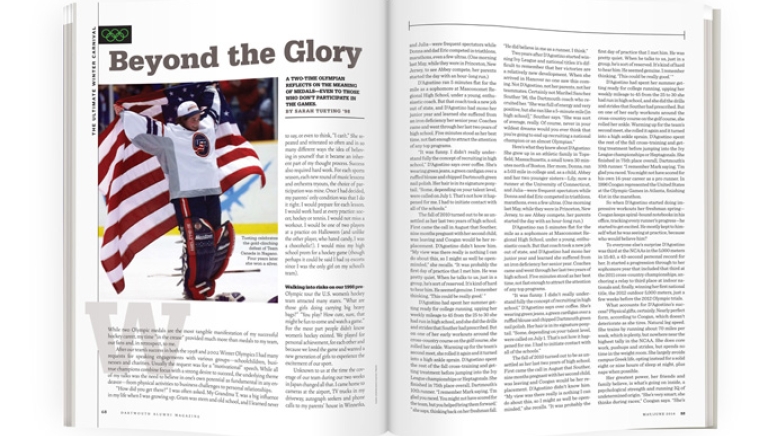

Walking into rinks on our 1998 pre-Olympic tour the U.S. women’s hockey team attracted many stares. “What are those girls doing carrying big heavy bags?” “You play? How cute, sure, that might be fun to come and watch a game.” For the most part people didn’t know women’s hockey existed. We played for personal achievement, for each other and because we loved the game and wanted a new generation of girls to experience the excitement of our sport.

Unknown to us at the time the coverage of our team during our two weeks in Japan changed all that. I came home to cameras at the airport, TV trucks in my driveway, autograph seekers and phone calls to my parents’ house in Winnetka, Illinois. We stopped looking over our shoulders to see whose autographs people wanted. We started embracing our responsibility as role models and, for some, heroes. I began to realize the gold medal wasn’t just about me and my personal goals, it also represented universal themes that connected me to more people than I could have imagined.

After winning gold in 1998 I retired from hockey and returned to Dartmouth. But my love of the sport and the peace I felt when I was performing at my absolute best drew me back to the ice. I missed the quiet mind, the meditation of being in the zone and the simplicity of all my focus and energy being directed at definable perfection. So I came out of retirement, well before Brett Favre made this fashionable. As an Olympian I felt blessed. As an American I simply could not pass up the opportunity to play in my own country. Once again I had a definable goal. However, just as I had changed in those four years, so too had the sport—and my perspective.

Where Nagano was a magical mystery tour of wide-eyed firsts, the campaign heading into Salt Lake City in 2002 was much different, as internal and external forces redefined our team chemistry. There were agents, sponsors and media, as well as veteran players, new players and an unpredictable coach. And we were now public figures. People knew who we were when we walked into a rink. They would be waiting for us, asking for autographs or just offering a nod of encouragement against our rivals. We gave clinics in most cities and we had young fans anxiously waiting for us in hotel lobbies. I tried to take it all in.

As an athlete it is so easy and necessary to remain highly focused on the practice or the game ahead, especially in the sterile environment created for athletes to avoid distractions. Four years after my first Olympic Games, however, I did not want to put the whole experience in a tiny box labeled “mine.” I wanted to see it from the eyes of a little girl who was meeting her hero instead of functioning as an athlete just wanting to make it to the bus and back to the hotel to meet a sponsor and grab some grub. I wanted to remain humble, approachable and compassionate, while unrelentingly focused on the task at hand. I learned to constantly adjust the balance of a myopic internal focus and a broader perspective as leader and role model to the public.

I’ve heard it said that athletes are an inherently selfish breed. It does take an immense amount of time, disciplined effort and sacrifice to train, which can leave a person tired and cranky, all of which require understanding and support from family and friends. There is pressure all the time—to make the team, to stay on the team, to win a starting position, to keep a starting position. These are personal triumphs, or so I believed.

Until we won.

I came to realize that winning Olympic medals was much bigger than the achievements of the 20 individuals to whom they were awarded. From the morning after our gold-medal victory in Nagano I started receiving and responding to e-mails. On that first morning, I read an e-mail from a 6-year-old girl who wrote to congratulate me and the team. She added that her mom had let her go to school late so she could see the end of our game, and she seemed somewhat astounded by this fact. I e-mailed her, thanking her and adding a few personal notes about the Olympics. She wrote that her mom had just agreed to exchange her unused figure skates for hockey skates.

The next e-mail was from her mother, telling me how we had made the country proud and how she had cried when we won. Then she thanked me for writing her daughter, for being approachable and personable and for the influence I had on both of their lives. It was my first dose of impact. I was surprised and humbled.

My favorite memory of the Olympics is of another letter I received, this one from a friend of my grandma. She wrote to me about losing her son to cancer more than 50 years ago. He was my age at the time, 21, and an athlete. The pain of the loss had kept her from reading about, watching or enjoying sports for almost half a century. However, as a friend of the proud Grandma T., she followed every minute of our team. She wrote personally about how she, too, had cried—for us, for our team, for herself and for her son. Watching the Olympics had given a piece of him back to her and now, long after the Olympics had ended, she continued to turn to the sports section first. She actually thanked me for giving that piece of him back to her. I wasn’t sure I deserved that thanks. I thought people were crying for us and for our team. It took longer than it should have to realize that we won a medal for them, too.

Sarah Tueting is a life/executive coach and lives in Park City, Utah, with her husband, Dan Lemaitre.