The flood of real-time big data, including information from smartphone GPS and high-resolution remote-sensing imagery, will greatly affect our maps, according to Chipman, an expert on applied spatial analysis and mapmaking. “It’s challenging to make sense of the volume of raw data generated by 21st-century society,” he says, “and geography is one of the tools people are most comfortable using to organize all that information.” Chipman, who leads the applied spatial analysis lab and teaches courses on topics such as geovisualization and remote sensing, says these factors will shape the evolving world of data mapping.

Spatial Data

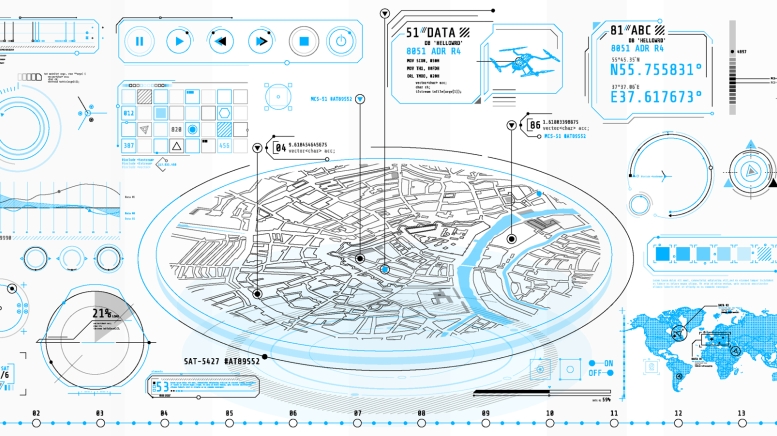

In the next decade data science will be spatial science. Beyond the use of imagery for mapping purposes, the torrent of geotagged data from mobile phones, cameras, vehicles, and other devices will facilitate the growth of spatially aware artificial intelligence. These systems will draw inferences about people, places, and phenomena by analyzing their spatial interactions. Privacy concerns have been somewhat discussed in the media—probably far less than they deserve—but there are also remarkable opportunities to improve our understanding of the world and answer questions such as “Where do people go who are displaced by a wildfire or a flood?” or “How do people’s social interactions change at the onset or the end of a pandemic?”

Drones

Drones, or uninhabited aerial systems (UASs), provide a revolutionary platform for advanced mapping technologies. They can rapidly collect vast amounts of imagery and 3-D topographic data at spatial resolutions much sharper than any other tool can provide. Now a researcher can go through a fairly straightforward flight certification process, take a lightweight UAS out into the field, and rapidly map any study region at centimeter resolution.

Satellites

Drones get all the attention, but the growing constellation of earth observation satellites provides systematic imagery worldwide at a range of resolutions down to the decimeter, across a wider spectrum of wavelengths of light than most UAS cameras, and with an accessible historical archive that includes the Landsat global archive of approximately 9 million images and more than 6 million gigabytes. In recent years this information has become much easier to access and use for long-term studies of social and environmental systems. It’s now free, available in real time, and easier to analyze.

Obstacle Recognition

UAS-based mapping projects face three hurdles. One is the sheer volume of information produced and a desperate need for better algorithms for the fully automated extraction of information from raw aerial imagery. That’s an area where there will be huge progress in the next decade. The second hurdle is that most UAS mapping projects are targeted at a particular area for a particular purpose, with no mechanism for sharing or archiving data and no attempt to provide systematic coverage over larger areas. The third hurdle is that the historical record is very short—we can keep revisiting and re-imaging places with drones to look for changes in the future, but we can’t go back to see what’s changed in the past, because low-cost commercial-grade drones available for scientific mapping use began to proliferate only in the past decade.