Reconstruction Radical

In the turbulent years of Reconstruction, lawlessness and violence ran rampant in the South. The conflict pitted Republicans—especially the Radical Republican wing that sought to protect the rights of 4 million newly freed Black men and women—against Democrats, whose political strength was rooted in a doctrine of white supremacy.

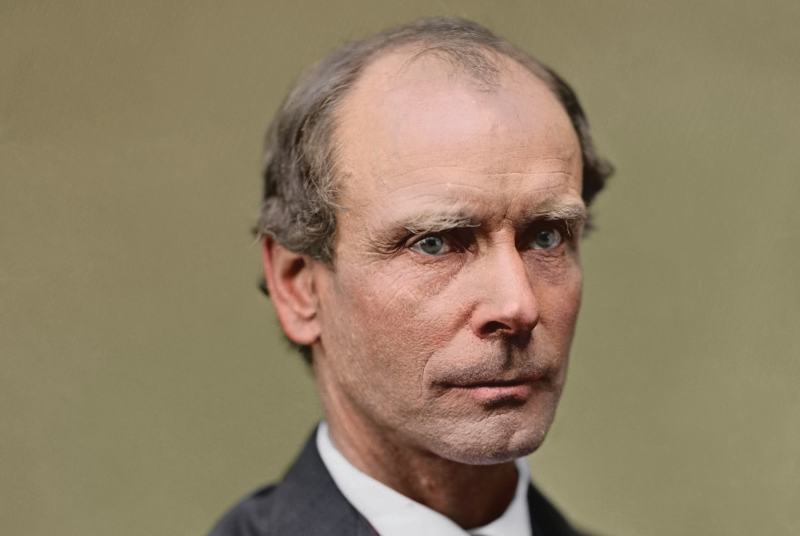

Amid this backdrop, a little-remembered Georgia lawyer and former slaveholder originally from New Hampshire rose to become the country’s top law enforcer under President Ulysses S. Grant. Although Amos Tappan Akerman served for only 18 months, he was “honest and incorruptible…one of the outstanding attorneys general in American history,” according to Ron Chernow’s authoritative 2017 biography, Grant.

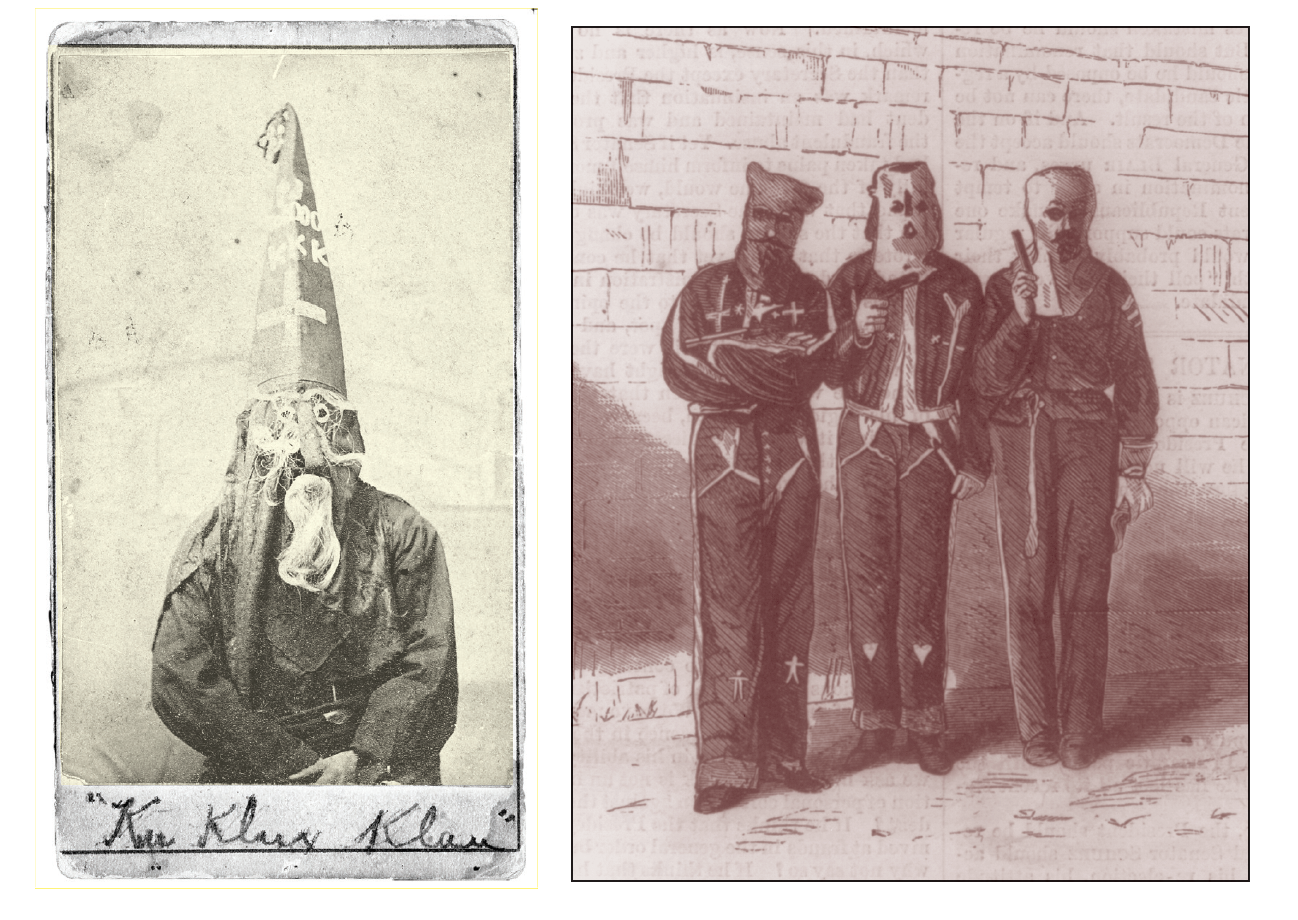

Akerman took on the menacing challenge of stopping the major perpetrators of Reconstruction terrorism, the Ku Klux Klan. The Ku Klux, as it was often called then, grew out of a relatively inoffensive social club formed in 1865 by a group of young professional men in Pulaski, Tennessee. In three years it rapidly metastasized throughout much of the South into a band of night-riding white supremacists who attacked Black families and a good many white Republicans as it sought to cripple the party and its supporters.

The Klan’s aims were “to destroy the Republican Party’s infrastructure, undermine the Reconstruction state, reestablish control of the Black labor force, and restore racial subordination in every aspect of Southern life,” writes Eric Foner, the preeminent historian of Reconstruction. He characterizes the Klan as “a military force serving the interests of the Democratic Party, the planter class, and all those who desired the restoration of white supremacy.”

Gangs of Klansmen wearing robes and masks rode in darkness to attack their victims, whipping, burning, raping, and killing, often leaving them hanging from trees. They did not spare women and children. Many of the Ku Kluxers were Confederate veterans prominent in their communities: merchants, lawyers, businessmen, even clergy. Sheriffs and local officials often donned masks and joined them. They made few arrests. Victims who sought the intervention of the law found themselves targeted for retribution, sometimes fatally.

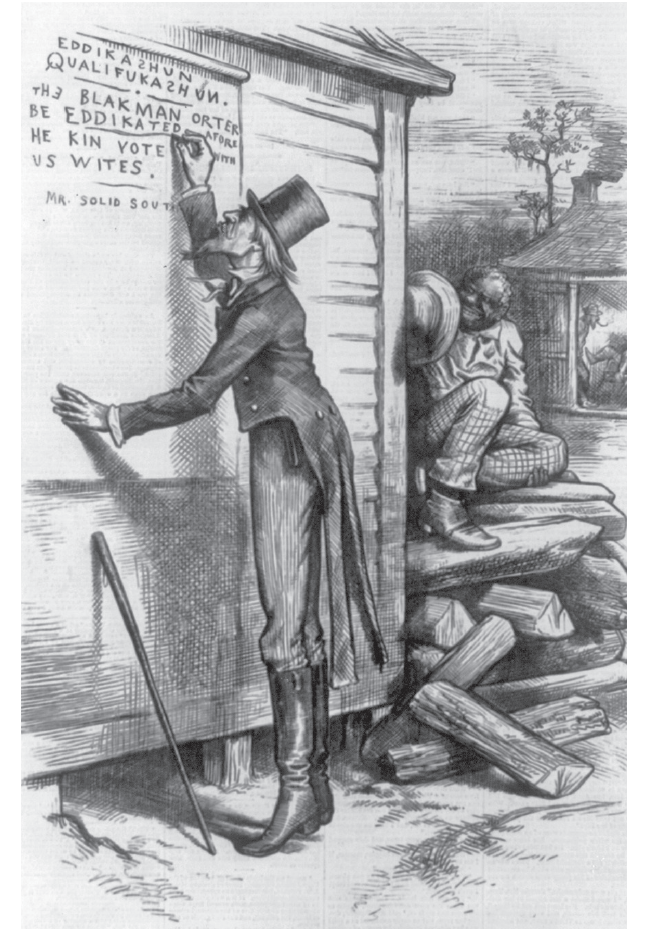

As a countermeasure, the solidly Republican U.S. Congress invoked the 1868 Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibited states from denying any person the equal protection of the laws, and the Fifteenth (1870), which prohibited states from denying any citizen the right to vote because of race. To implement these amendments, Congress in 1870 and 1871 passed the Enforcement Acts, a series of laws that made it a federal crime to “go in disguise upon the public highway or upon the premises of another” to deprive any person of equal protection or to conspire to use force or intimidation to obstruct any person from voting. As Congress intended, Akerman seized upon this significant expansion of federal authority.

The new attorney general’s abhorrence of the Klan’s actions was visceral. “That any large portion of our people,” he wrote in his diary, “should be so ensavaged as to perpetuate or excuse such actions is the darkest blot on Southern character in this age.”

Akerman decided to focus his efforts on the upland corner of York County, South Carolina, where the KKK was pervasive. The Enforcement Acts authorized President Grant to suspend habeas corpus, thereby permitting the arrest and jailing of suspects with no recourse to a court. Akerman prevailed upon Grant to suspend habeas in York and then sent federal marshals—the new law enforcement arm of the U.S. Justice Department—to arrest Klan kingpins. Some leaders fled into neighboring North Carolina, others as far as Canada. Many Klan foot soldiers turned themselves in and, hoping for leniency, provided information on their officers. Some Klan cells surrendered en masse, leaving the marshals with more lawbreakers than they could possibly try.

Akerman wanted to do more than convict motley, low-level hoodlums—he wanted Klan leaders. With the U.S. district attorney for South Carolina—fellow Dartmouth graduate David Corbin, class of 1857—he devised a litigation strategy. They decided to use the trials of the York County Klansmen to secure rulings from the federal court in South Carolina that confirmed the constitutionality of the Enforcement Acts, which they could then use to convict Klansmen of the atrocities local authorities ignored. The federal government had never before attempted to prosecute those crimes, but Akerman and Corbin felt the newly enacted laws could provide the sweeping expansion of national authority they had in mind.

If Akerman and Corbin succeeded, they would establish that the violent denial of civil rights was not only a new crime but a new kind of crime—a federal offense, to be prosecuted by federal prosecutors in federal courts that bypassed local judges disinclined to crack down on their Klan neighbors.

Akerman had spent 25 years after graduation often aimless and morose—until a tentative step into politics led him in just three years to the highest legal office in the country, an office whose authority he energized and, in many ways, defined.

He was born in 1821 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the ninth of 12 children raised to work hard on the family farm. In his diary he said he also managed to be a “tolerably good scholar.” At 15 he enrolled at nearby Phillips Exeter Academy. In 1839 his grandmother and an Exeter classmate loaned him $325 to attend college. Akerman traveled to Hanover and was promptly admitted as a sophomore. He became president of the debating society and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. In his senior year he was an editor of The Dartmouth, then a startup literary magazine. At his Commencement he gave an address on “The English Poets as Advocates of Liberty.”

By 1846 Akerman made his way to Savannah, Georgia, to work as a tutor to the children of John Macpherson Berrien, a U.S. senator who had been attorney general under President Andrew Jackson. Though unsure whether he wanted to pursue a legal career, Akerman spent his afternoons and Saturdays reading law books in the local courthouse. With little more preparation than that and a few months of apprenticeship in a law office, he applied for admission to the Georgia bar. He opened a law practice the following year in rural Elberton and began farming on the side.

At 34 he was bereft of any romantic relationships. “My life is lonely,” he lamented in 1855. “Would circumstances permit it to be more social, I should be gratified. I am daily sensible of the evils of solitude.”

In 1863 Akerman joined the local unit of the Georgia militia. He also met Martha Galloway, a local schoolteacher 20 years his junior. In May 1864, when he received notice that his unit was being activated, they quickly married. The next day he departed for Atlanta.

Although he had been a Unionist with little sympathy for secession, he seemed to regard slave ownership matter-of-factly. Akerman wrote to his wife a month after their marriage, as she prepared to move to Elberton, providing her with the names and ages of the 11 “negroes” she would find there, only one of whom was “hired.” Akerman also wrote of his hope that when the war was over “we can subside into plain husband and wife, and if Heaven will let us, lead quiet and peaceable lives.” After a few months without seeing action, his unit disbanded, and Akerman returned home.

In 1867 Akerman was elected his county’s delegate to the Georgia convention to draft a new constitution, as required by Congress for readmission to the Union. He emerged as a prominent speaker and caught the eye of newly elected Grant, who named him the U.S. district attorney—what is now called U.S. attorney—for Georgia. The following year Grant appointed him U.S. attorney general, the first to preside over the newly created U.S. Department of Justice. Only five years after his service with the Confederate Army and less than three years after his first public role at his state’s convention, Akerman had risen with exceptional speed to become the nation’s chief federal law enforcement officer, as well as the first Southerner in a postwar presidential cabinet. Grant’s nomination of Akerman on June 16, 1870, stunned most of the nation. “Universal Surprise at the Choice,” headlined The New York Times.

He was a man of some paradox: a New Hampshire native turned Georgian, a Unionist who became a colonel in the Confederate Army, a former slaveowner who at the state convention advocated “equal and political rights for all men,” a man whose opponents found him “cold-blooded, calculating, persistent, energetic, and tireless” and who yet was described by a reporter as a man of “affable manner, with a quiet self-possession, which make him at the same time easy of approach and dignified of demeanor.”

In taking on the KKK, Akerman and Corbin faced formidable headwinds. Southern Democrats raised enough money to retain Reverdy Johnson of Maryland and Henry Stanbery of Ohio, each a former U.S. attorney general, as heavyweight defense counsel for the accused Klan members.

The issue before the court was clear: Could Congress authorize the Justice Department to prosecute and punish men who threatened, abused, and killed Black citizens to prevent them from exercising their constitutional rights? If the U.S. government were denied this authority, the real issue was whether Black citizens would have any constitutional rights at all.

The defense sought to persuade the court to dismiss the defendants’ cases, contending that the Enforcement Acts in no way authorized Congress to create new federal crimes, much less crimes based on threats, assaults, and murders. Such prosecutions were the traditional responsibility of the states, the defense argued, and the national government’s assertion of authority was an unconstitutional overreach.

After seven days of arguments, the court ruled mostly in favor of the defense. But it upheld the validity of indictments against conspiracies that impeded the rights of Black voters. Although the court had rejected their novel constitutional arguments for a muscular reading of the law, Akerman and Corbin pressed forward with prosecutions based on conspiracy, and in the following weeks Corbin won convictions of Klansmen in four cases. The legal duo had successfully developed a strategy that could be used in later trials. As the Department of Justice proceeded to arrest Klansmen when it could and won convictions and prison sentences, Klan members grew unnerved and the group fragmented and collapsed. “By 1872, the federal government’s evident willingness to bring its legal and coercive authority to bear had broken the Klan’s back,” writes Foner, “and produced a dramatic decline in violence throughout the South.”

Still, endemic racism persisted. White supremacists regrouped into small offshoots and Jim Crow laws ensured that former slaves and their descendants would remain subjugated well into the future. Congress repealed the Enforcement Acts in 1876 and the government abandoned Reconstruction. Southern states circumvented the Fifteenth Amendment with literacy tests, poll taxes, and property requirements to deny Black citizens the ability to register and vote. Atrocities continued.

A new generation revived the Klan in the years after World War I. The Supreme Court upheld segregation in schools and public

accommodations for 70 years. But the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s mitigated these practices—largely based on the arguments that Akerman and Corbin had raised.

In 1872 Grant asked Akerman to step down—“much too soon,” according to Chernow—probably because Akerman riled railroad moguls seeking government largesse to expand. If Akerman was frustrated that he had been denied necessary resources to continue Klan prosecutions, he said nothing publicly about it. He declined Grant’s offer of a federal judgeship and returned to his law practice, cornfields, and family.

Prosecutions continued, but they decreased, as both resources and public support deteriorated. The outrages of the KKK recurred only sporadically and in isolated locations. It was under Akerman’s “inspired leadership,” Chernow concluded, that the “Klan had been smashed in the South.”

When Akerman left Georgia for Washington, D.C., in 1870, he and his wife had three sons under the age of 5. After his return, she gave birth to four more sons. The youngest was only 18 months old when Akerman died of inflammatory rheumatism a few days before Christmas in 1880. He was 59.

“Akerman left an enduring legacy of courageous leadership during challenging times,” a U.S. attorney wrote last January in a Justice Department journal. “The window of opportunity for dynamic and effective Klan prosecutions was a narrow one, and Akerman made the most of it.”

Allan A. Ryan teaches constitutional history at Harvard University’s division of continuing education. He previously served as an attorney with the U.S. Department of Justice.