River of Fury

In the summer of 1933, Leich made the first voyage from the Colorado River’s headwaters at Grand Lake, Colorado, to its junction with the Green River in Utah as part of a planned journey to the Pacific, a saga documented in his book Alone on the Colorado.

In the summer of 1933, Leich made the first voyage from the Colorado River’s headwaters at Grand Lake, Colorado, to its junction with the Green River in Utah as part of a planned journey to the Pacific, a saga documented in his book Alone on the Colorado.

“I fully recognized the risks that a single-handed voyage entailed, with no safety margin,” he wrote. “I was drugged—bewitched—by a roaring golden river two thousand miles away that I had never seen.”

Growing up in Indiana’s cornfields, Leich fell in love with the outdoors, a romance that grew when he arrived in Hanover in 1925. He spent nearly every weekend at Dartmouth hiking, skiing, or snowshoeing.

His voyage ended in Utah’s Cataract Canyon. Angry rapids wrecked his boat, and he had to hike out of a forbidding wasteland. Hallucinating, he stumbled on a ranch where he sank to sleep in “thankful exhaustion.”

Leich spent his career with the Civil Service Commission in Washington, D.C., and remained an active outdoorsman. He passed away in 1981 at age 72.

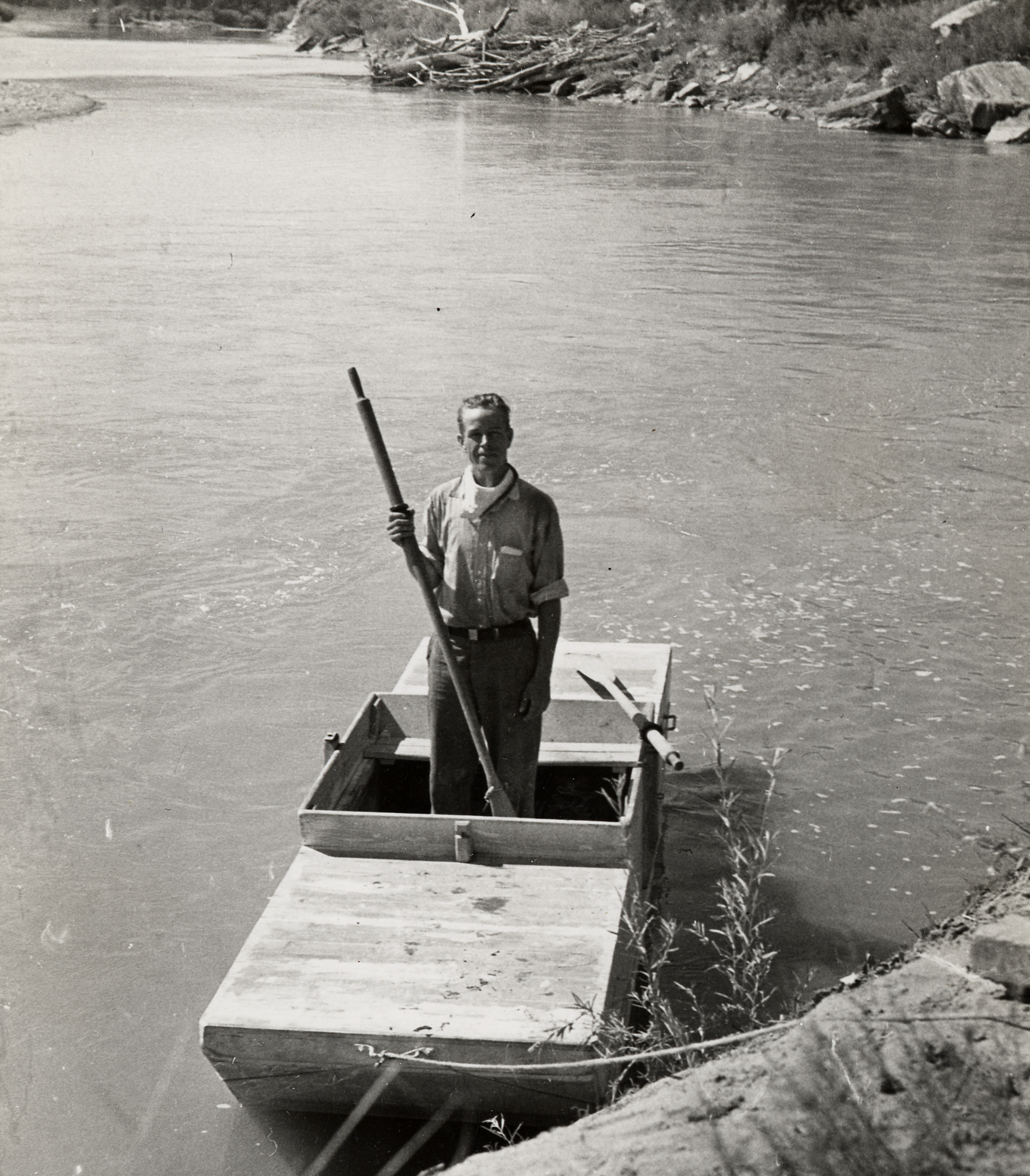

This excerpt captures him and his boat, the Dirty Devil, with the “fury of the river” ahead.

When I had finished bailing out the boat after breakfast, I left the bucket half-awash on shore and packed up my camping outfit. In loading the boat later, I found that the bucket had disappeared and spent fifteen useless minutes diving for it along the sandy bottom, since it might be crucial in a future swamping. Luckily, I found it drifting in an eddy two miles below when I resumed the voyage.

The river coursed for miles through low sandstone canyons, but farther back from shore higher cliffs and mesas hemmed in the valley. I enjoyed the changing panorama as I swam in the sunlit current alongside the bobbing punt. Around noon I was sunning myself on the aft deck, letting her drift broadside with the oars dangling overboard, when the river gave an unexpected demonstration of its power. The downstream oar caught on the shallow bottom and the heavy iron rowlock snapped off clean. I had some extras along, but this was another lesson in how a minor lapse might endanger the success of a single-handed endeavor.

In the heat of midday the vest-pocket thermometer from my refrigeration days showed a temperature of 110 degrees in the shade. I found that I did not mind this too much. I was wearing a khaki shirt of woolen flannel and this served as insulation against the sun and the hot, dry air. Back east it would have been intolerable at 80 degrees in the usual energy-sapping humidity.

Throughout the afternoon the Dirty Devil swept around one curve after another beneath vertical walls of stratified rock. On the inner shore of the bend there was usually a small “bottom,” or overgrown sandbar, and on the outer curve the river cut directly into the sheer red walls. Peterson told me how two prospectors had lost their boat in the ice a short distance above the Green River. Unfamiliar with the trails up on the plateau, they tried to make their way upstream by swimming across from one bottom to another. Luckily a hunting party from Moab showed them a trail across the upland.

Threatening clouds gathered over the still canyon late in the after-noon, accentuating the gloom of the rocky depths. The dark river seemed to brood on its self-inflicted captivity. Three white herons or egrets rose from the shore without a sound and flew slowly down the canyon, their pallid bodies contrasting with the somber walls. It was easy to understand why their wraith-like presence was often considered an evil omen.

A magnificent spectacle unfolded when I made my camp after rowing twenty-three miles for the day. A great square butte rose above a confusion of rock several miles north of the river. As I landed the sun broke out beneath a storm cloud. The flaming rays colored the belly of the nimbus mass and tinted the crest of the butte. Thomas Moran, painter of western canyons in the 1870s, would have delighted in the majesty of the view.

Darkness swiftly followed this vivid sunset and narrowed my vision to the circle of sandy beach in the firelight. Lightning flashes showed the Dirty Devil tugging at her moorings in the rising wind. I walked down to the water’s edge to check the ropes while claps of thunder echoed up and down the gorge. When I returned to camp to spread my blanket under the tarpaulin I glanced at the dying fire and gasped in astonishment. The glowing coals formed in a perfect image the face of a hideous grinning devil. “Good thing I’m not superstitious,” I thought, unable to turn my face from the spectacle. Shaken more than I cared to admit, I kicked sand over the embers to destroy the apparition. The storm broke loose shortly after I crawled in for the night.

Saturday was gloomy and stormy. During the morning I rowed a serpentine course down a sullen river, passing out of the broken valley into a steeper, more precipitous canyon that extended all the way to the Green River. For the first hour the great, isolated butte tapered to the sky in majestic inaccessibility. Scenes of the wildest beauty followed one another around every bend of the canyon. Incredible rock remnants soared into the clouds and sheer cliffs displayed the record of millenniums of ocean deposition. If I had wanted to get away from my fellow men I was surely succeeding.

Scenes of the wildest beauty followed one another around every bend of the canyon.

At noon I reached the beginning of the Loop, a bowknot bend where the Colorado made a nearly perfect figure-eight design, entrenched more than a thousand feet below the rim. The river flowed eight miles to cover an airline distance of two and a half. At one spot the distance between the two meanders was only six hundred feet across an isthmus, where the vertical walls were breached until just a low heap of rubble separated the two channels. Here again was a vivid lesson in geomorphology—a prize example of Powell’s theory of antecedent streams. Evidently the ancient Colorado had meandered in oxbow bends across a level plain like the lower Mississippi, and when the whole region began to rise the river continued in its channel, cutting down as the land rose. Now it was trapped in its ancient meanders far below the original land surface.

As I entered the Loop, several violent whirlwinds—forerunners of a thundersquall—swept up the canyon like miniature tornadoes, carrying tumbleweeds three hundred feet into the air. The main storm, roaring out of the hot, rocky wilderness to the southwest (a desert breeding ground of thunderstorms), caught the Dirty Devil in midstream on the first loop. The wind and the waves were so furious that the boat was actually borne back upstream, pitching and tossing despite my best efforts at the oars. Then a respite allowed me to round the bend while the wind, lost in the labyrinth, went moaning around the corners of broken walls in capricious gusts. On the other side of the first loop, the full force of the storm gathered astern and the pitching boat spooked beneath high, undercut cliffs. The continuous reversal of direction had me dizzy by the time the boat escaped from the maze, in midafternoon.

Now the river took a more direct course to the southwest and the canyon walls became ever higher and more spectacular. On the right bank I passed the Slide, a huge rockslide where the whole side of the canyon had come down in a heap of fragments the size of small houses, obstructing the river halfway across its bed. There was scarcely a ripple in the constricted channel, but in high water the current must flow like a millrace.

Another thunderstorm scoured the canyon as the boat wound around some bends below the Slide. In the early evening I was surprised to reach the mouth of the Green River, flowing in from the north out of the deep gorge of Stillwater Canyon. One moment I looked ahead and saw nothing but a blank rock wall; the next I saw I was rounding a formidable headland at the lonely confluence. Where the waters mingled the two rivers seemed to be of equal size. Whether the Green or the old Grand was the true source, I was now sailing indisputably on the main Colorado River, having completed the first voyage from the headwaters to the junction.

Shortly before my trip, a Colorado River navigator wrote that fewer than one hundred men had seen this spectacle at the junction of the Green and the Colorado. True enough, no tourists yodeled beneath the pinnacles of the Land of Standing Rocks when I arrived, but it is certain that many trappers, hunters, explorers, prospectors, geologists, engineers, archeologists, and ranchers had preceded me on their varied missions. An open skiff at Moab and ten days’ provisions, with enough muscular reserve for the upstream pull on the way back, are the only requisites for the journey. Actually, ancient trails and stone dwellings indicate that human beings inhabited this region long before the first Caucasian ventured to the site. No doubt the rainfall was greater in the days when the cliff dwellers lived here.

Without exception the major Colorado River expeditions had come down the Green River rather than the Upper Colorado. This practice, beginning with Major Powell, came about because of better railroad facilities on the Green River. Powell started from the Union Pacific crossing that had just been completed in Wyoming. Many later parties started from the Denver and Rio Grande crossing at Green River, Utah, 117 miles upstream from the confluence.

The still waters of the Green and the Colorado between Moab and the town of Green River aroused great hopes at one time for navigation of the canyons. Several attempts were made to establish steamboat service between the two places, but the hazards of sandbars and riffles were too great. A fifty-five-foot sternwheeler, the Undine, plied the canyons for a few trips but was lost in a riffle. The Major Powell made a couple of trips but was found to have too deep a draft. One vessel, optimistically called City of Moab, was dismantled after an unsuccessful trial and shipped away piecemeal to the Great Salt Lake.

Some years ago, the citizens of Moab persuaded the U.S. Army engineers to survey the canyons in order to remove navigational hazards. The survey showed that twelve riffles of the Green River would have to be dredged and the Slide cleared to make a channel for moderately large vessels. The latter job alone was priced at $100,000 at the low costs of 1909, and nothing came of the proposals. But today these once-still canyons resound to the reverberations of outboard motors; in 1959 more than four hundred boats took part in an annual two-hundred-mile cruise from Green River to Moab.

It is easy to see why the Ute Indians called this region the Land of Standing Rocks. The canyon walls tower on each side to a height of 1,500 feet, rising through layers of stratified rock to the series of pinnacles and minarets that give the region its name. The country is typical of the high plateau that extends through southern Utah and northern Arizona. The arid upland, dissected by countless intermittent streams and dry washes, has been eroded into buttes, mesas, and solitary monoliths. The main rivers run in trenches far below the surface of the land and their tributaries, even those that flow only after thundershowers, have carved deep channels into the solid rock as they seek the level of the rivers.

At the mouth of the Green River I followed again in Powell’s track—in his wake this time instead of in his footsteps. He had floated down to the confluence twice, in 1869 and 1871, exploring, geologizing, and surveying. The precision of his work under difficult conditions can be gauged by the river elevation that he calculated at the junction in 1871: 3,860 feet above sea level. Later surveys with more accurate instruments placed the elevation only sixteen feet higher.

Powell’s fanciful description of the prospect near the confluence hints at the overpowering impression the canyon walls make upon a voyager:

Away to the west are lines of cliff and ledges of rock—not such ledges as you may have seen where the quarryman splits his blocks, but ledges from which the gods might quarry mountains, that, rolled out on the plain below, would stand a lofty range; and not such cliffs as you may have seen where the swallow builds its nest, but cliffs where the soaring eagle is lost to view ere he reaches the summit.

Strange stuff to find under the prosaic imprint of the Government Printing Office!

I continued downstream at sunset and approached the very line of cliffs that Powell had eulogized, although my 20/20 vision spotted no soaring eagles either at the base or near the summit. This rampart seemed to block the river’s course to the west, but when the current swept against the wall it made a sharp curve to the south and soon plunged into the first rapid of Cataract Canyon. A large whirlpool swirled in the outer corner of the bend, where tightly packed debris ranged along the bank. A crude plank bridge, washed down many miles from the region of civilization, balanced intact on the top of a large boulder.

Half a mile below the bend, opposite a wall capped by pinnacles, I camped on the left shore just above the first rapid. Its muttering was a welcome relief from the silence of the upper canyons. I could find no mooring for the boat, so I tied the line to a corner of the ground cloth under my blanket. I hoped this arrangement would wake me up in case the boat broke away during the night, for I had no desire to start walking or swimming the 70 miles back to Moab or the 130 to Green River.

As the firelight flickered into embers, I realized that my dreams of many months were coming true. The preliminaries were over and I was on the big river at last. Tomorrow the main event started. This was all right with me; like Tennyson’s Ulysses, I told myself my purpose holds to sail beyond the sunset, and the baths of all the western stars, until I die.

Reprinted with permission from the University of Utah Press.