You notice the eyes first. Hard as marbles, dark as death, they can send a chill through the cheapest of 1950s B-movies. Beneath those eyes is a prow of a nose, then a mouth that can broaden in fraudulent welcome or, more likely, twist into a sneer. It’s a metaphysical sneer. It knows things about the world most of us are frightened to admit.

On the face of it, Robert Ryan had a pretty good run in Hollywood—credited in 70 films and several television movies and series—but why wasn’t he an even bigger star? As one of the most striking new talents to arrive on the post-WW II Hollywood scene, Ryan made an indelible mark in crime films, westerns, war movies, melodramas and more. When he was billed second or third, he almost always stole the show. When he was top-billed, you knew the film was going to have more going on—more dark energy, more repressed emotional violence—than the standard studio confection.

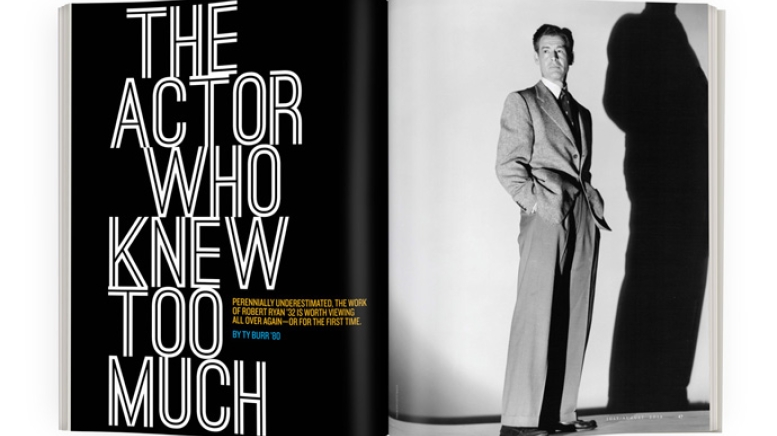

Ryan had the looks of a screen idol. A lean, dynamic 6-foot-4, he radiated Black Irish glamour, and women tended to act goofy when he was in the room. He had stage training and could act. He was thoughtful and articulate with directors and crewmembers alike. He was a good guy, stayed married to the same woman for 40 years and—rare in Hollywood—preferred to act on his politics rather than talk about them.

All the pieces are there for an iconic career, yet while peers Kirk Douglas, Burt Lancaster and Robert Mitchum achieved lasting pop-culture fame, Ryan is barely remembered to audiences who weren’t around during his prime. No boxed sets of DVDs are devoted to his oeuvre. There’s only one Ryan biography—the dutiful and scholarly 199o work by Frank Jarlett titled Robert Ryan: A Biography and Critical Filmography.

This is a mystery, and one for which there may be more than a single solution: For one thing, the movies in which Ryan got top billing aren’t held up as classics even when they should be. The Ryan movies that are remembered—1947’s Crossfire, 1955’s Bad Day at Black Rock, 1969’s The Wild Bunch—cast him as villains or in secondary roles.

Yet those villains were amazing. Many actors can convey malice, but when Ryan was cooking he was able to project a concentrated sense of evil that takes your breath away. The Racket is a fairly uninspired crime thriller from 1951, but Ryan’s old-school gangster, Nick Scanlon, has a thuggish urgency that’s genuinely unpredictable, and his devotion to his college-kid little brother is both touching and more than a little creepy.

Then, too, there’s the sense that Ryan resisted top-tier fame and that the doubt that animates his best performances—at times his characters’ self-loathing seems existential—extended off the screen. Ryan was a reluctant movie star, happy to take on challenging roles but forever leery of the Tinseltown charade. “He was ambitious as an actor,” said one of his closest friends, playwright Millard Lampell, “but as far as the kind of hustling that goes on in Hollywood is concerned, it was against his character.”

In that tension between physical power and spiritual unease, Ryan was a key post-war star, reflecting the ambivalence of an era that craved a return to innocence but had seen too much of the world to believe in it. There’s a reason he starred in so many film noirs, the shadowy genre that hashed out the dissonances of late-1940s/early-1950s American life. To see Ryan as a vicious anti-Semite in Crossfire, the thriller that brought him recognition as a star (and a best-supporting actor nomination from the Motion Picture Academy), is to see the raging, racist id that the culture was trying to stuff back in its box in the wake of WW II.

Even more startling is Act of Violence, a noir that came out just after Crossfire but flew in under the cultural radar. Made by an up-and-coming director named Fred Zinnemann, the film stars Van Heflin as a heroic WW II veteran, a pillar of his small-town community and loving husband to a very young Janet Leigh. It should be all sweetness and light, but Zinnemann shoots it as a black-and-white nightmare in which Ryan plays the hero’s platoon-mate, back from the dead with knowledge of his commanding officer’s wartime cowardice.

Ryan is terrifying in the movie. His face a numb mask, a bum leg scraping on the pavement, he’s an implacable figure of revenge—and he turns out to be the film’s damaged conscience. The hero is a villain, the villain a hero, and that’s what film noir understood about post-war America, and what Ryan seemed to understand, too. So when it came time to play the hero himself in the heartbreakingly fine 1949 boxing drama The Set-Up, Ryan could find all the ruined nobility in the washed-up fighter Stoker Thompson while staying true to the film’s vision of a fallen world.

Where does such knowledge come from? Did Ryan pick it up in the ivied halls of Hanover? Probably not, even though the Great Depression was deepening its hold during the years the actor attended Dartmouth. Ryan was the wealthy son of a workingman who had made good—his father ran a construction company with major city contracts in Chicago—and the boy’s youth was a charmed one. That may be a source of his later reticence. “Dad didn’t have the kind of drive that somebody like Kirk Douglas had,” said Ryan’s son Tim. “Money was something he was kind of used to.”

Ryan arrived at Dartmouth in the late 1920s with a broadminded Jesuit education from Loyola Academy in Chicago, and he proved to be as fast with his fists as with his wits. Ryan was the College’s boxing heavyweight champion four years running, lettered in football and track, wrote for The D and, according to his biographer, “was involved in anti-Prohibition activities”—which could mean anything from downing a few beers to running Scotch over the Canadian border. Professors Benfield Pressey of the drama department and Brooks Henderson of the English department stimulated an early interest in Shakespeare, and the searching turn of Ryan’s mind can be gauged by the one-act play he wrote his junior year. It was an earnest death-takes-a-holiday drama called The Visitor. It won him a $100 prize.

None of which prepared the future actor for the world. After a failed attempt to become a journalist in New York City, the young Ryan grabbed a ship bound for Africa and worked as an engine room janitor for two long years. He dug subway tunnels in Chicago, mined for gold and punched cattle in Montana and, back in Chicago, sold cemetery plots and steel products. The low point came with a stint as a bill collector for a loan company, shaking poor people down for money they didn’t have.

Out of desperation Ryan took a job directing a play at a private school and later said he “was bitten by the acting bug watching those kids.” By 1939 he was in Los Angeles studying drama with the legendary Max Reinhardt. By 1940 he had a contract with Paramount and a debut movie under his belt. It was called Golden Gloves, and although Ryan was originally supposed to play the lead, the studio decided he wasn’t ready and relegated him to a bit part. Years later director Eddie Dmytryk admitted, “Perhaps we weren’t ready for him.”

By WW II Ryan had jumped to RKO, and in 1944 he joined the Marine Corps, becoming a drill instructor at Camp Pendleton in San Diego. The experience of sending young men off to war and seeing many of them return physically and psychologically maimed seems to have darkened his soul considerably and led to a lifelong devotion to pacifism. (In the late 1950s Ryan became actively involved with the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy. When his family received right-wing death threats in 1962, Ryan’s friend and co-star John Wayne stood guard outside the actor’s house with a rifle.)

Whatever happened to Ryan during the war, his breakthrough performance as a Jew-hating Army veteran in Crossfire seems to intuitively understand the sickness that can live in men’s hearts. In no way is it a sympathetic performance, but it is absurdly charismatic: Ryan’s Montgomery is a villain you love to hate.

The career was launched, but even during the peak of Ryan’s early productivity he was rarely cast as a straight-up hero or even a flawed-but-noble tough guy of the sort Mitchum and Douglas cornered the market on. Ryan simply seemed to know too much. In 1952’s On Dangerous Ground the actor plays Jim Wilson, a big-city police detective barely keeping his sadistic tendencies in check. The film sends the character out to the snowy countryside to solve a case and fall in love with a blind woman (Ida Lupino), but none of that can erase the early scene of Wilson laying into an “interrogation” victim with the joyous, helpless cry, “Why do you punks make me do it? Why?”

As a contract player with a hard-to-define image, Ryan was stuck in too many forgettable films in the 1950s. Clash By Night (1952) looks great on paper: Storied director Fritz Lang filming a Clifford Odets play with Barbara Stanwyck and a very young Marilyn Monroe in the cast. It’s a stagey snooze except when Ryan is onscreen as Earl, an insecure bad boy who steals Stanwyck away from her fisherman husband. The actor was tall, handsome. He looked godlike in a tight Hawaiian shirt. Yet he conveyed a loser’s self-disgust with frightening clarity.

When Ryan played parts that didn’t call for doubt, he was simply frightening. Caught is a 1949 MGM melodrama from director Max Ophuls that didn’t get much attention at the time but that now looks like a classic fusion of film noir and women’s weepie. Barbara Bel Geddes (later Miss Ellie of Dallas) plays a young naïf who marries a rich control-freak named Smith Ohlrig. In the latter role, Ryan creates an ego-monster who bears an uncanny resemblance to billionaire Howard Hughes—who happened to own RKO and was, in effect, the actor’s boss.

Despite these performances, Ryan’s career stalled in the mid-1950s. How do you pigeonhole a guy who looks like a hero but refuses to act like one? He turned increasingly to westerns, some excellent (he almost swipes 1953’s The Naked Spur from Jimmy Stewart), others routine. As a small-town bully in Bad Day at Black Rock, Ryan gets off a monologue that reveals the lonely soul behind a racist’s jingoism. He did TV and Shakespeare on stage, the latter hinting at the challenging roles he always yearned for and rarely got.

By the 1960s he was a survivor, with an aura of doomed regret clinging to his final performances. Ryan was shocked when the producers of the 1961 Jesus biopic King of Kings called to cast him as John the Baptist. He was certain they wanted him to play Judas. His Claggart in 1962’s Billy Budd was his last masterpiece of unremitting evil—the smile on his face as Billy strikes the killing blow is worthy of Melville’s original conception—and he seemed to summon up all the autumnal contradictions of the dying frontier as the bounty hunter of The Wild Bunch.

At the very end, he got the role he wanted and deserved. Ryan had always felt an affinity for the plays of Eugene O’Neill—both men came from wealth and larger-than-life fathers. Both were lapsed Irish Catholics who knew the soothing dangers of drink. A film version of The Iceman Cometh cast Ryan as Larry Slade, the play’s ex-anarchist and tormented barroom conscience, and he leapt at the opportunity.

It’s a magnificent performance, the best Ryan ever gave. Of all the rummies in Harry Hope’s saloon, Larry is the one who takes the long view. He sees both the futility of dreaming and the need for it. Ryan grew his hair out into a lank, leonine mane, and the neurosis of his early roles seems burned away. All that’s left is honesty.

By the time filming started Ryan had temporarily beaten back cancer only to lose his wife, Jessica, to the disease. He would be dead himself before The Iceman Cometh hit theaters in 1973. When Larry says, “What’s before me is the fact that death is a fine, long sleep, and I’m damn tired,” every word rings clear and true.

Larry also says, “I was born condemned to see both sides of the question.” That could serve as Robert Ryan’s epitaph—the lament of a Hollywood hero who knew too much to trust Hollywood heroism.

Ryan’s Top 10

Ty Burr recommends the following as Ryan’s best work. (Click on title to view a scene from the movie.)

1. Crossfire (1947) Ryan arrives on the scene, playing a vicious anti-Semite who realizes too late the post-WW II world has no room for his kind.

2. Act of Violence (1948) Film noir in suburbia, with the star unsettling and unstoppable as hero Van Heflin’s wartime guilty conscience.

3. Caught (1949) Ryan daringly plays his control-freak oil tycoon as a series of riffs on millionaire Howard Hughes.

4. The Set-Up (1949) One of the great boxing movies—and an acknowledged influence on Raging Bull—with Ryan electrifying as a washed-up pug.

5. On Dangerous Ground (1952) “When you talk to me, there’s no pity in your voice,” says blind Ida Lupino to damaged cop Ryan. And he’s the good guy.

6. Clash By Night (1952) A flawed film, but the star offers a study in self-loathing as a handsome but insecure philanderer.

7. The Naked Spur (1953) Ryan made many westerns, but this may be the best, with the star a likeably hateful villain opposite Jimmy Stewart.

8. Bad Day at Black Rock (1955) Another finely etched portrait of all-American evil—a small-town big shot complicit in a racist murder.

9. Billy Budd (1962) Claggart, Melville’s Mephistophelian master-at-arms, is one of Ryan’s most nuanced and complex—and oddly sympathetic—villains.

10. The Iceman Cometh (1973) A hard-to-find DVD—check your local library—but it’s Ryan’s finest four hours as barroom philosopher Larry Slade.

Ty Burr, the longtime film critic for The Boston Globe, lives in Newton, Massachusetts. His latest book, Gods Like Us: On Movie Stardom and Modern Fame, will be published in September.