“Don’t Join the Book Burners”

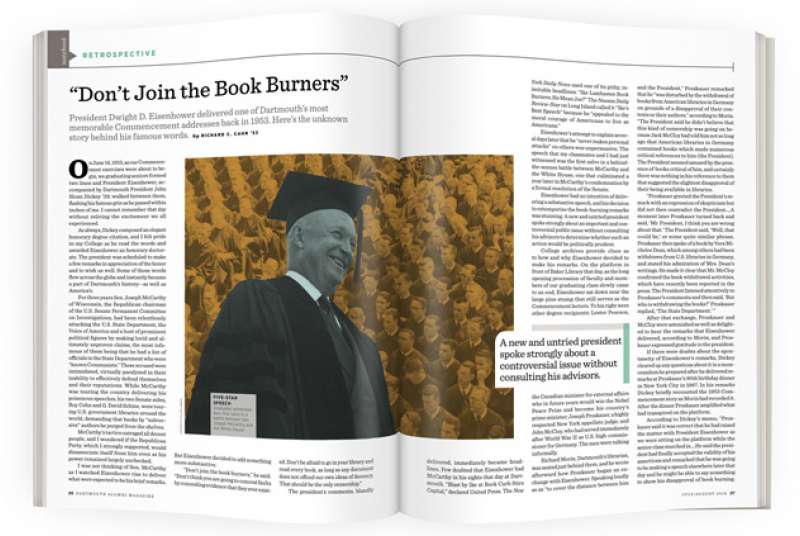

On June 14, 1953, as our Commencement exercises were about to begin, we graduating seniors formed two lines and President Eisenhower, accompanied by Dartmouth President John Sloan Dickey ’29, walked between them, flashing his famous grin as he passed within inches of me. I cannot remember that day without reliving the excitement we all experienced.

As always, Dickey composed an elegant honorary degree citation, and I felt pride in my College as he read the words and awarded Eisenhower an honorary doctorate. The president was scheduled to make a few remarks in appreciation of the honor and to wish us well. Some of those words flew across the globe and instantly became a part of Dartmouth’s history—as well as America’s.

For three years Sen. Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, the Republican chairman of the U.S. Senate Permanent Committee on Investigations, had been relentlessly attacking the U.S. State Department, the Voice of America and a host of prominent political figures by making lurid and ultimately unproven claims, the most infamous of them being that he had a list of officials in the State Department who were “known Communists.” Those accused were intimidated, virtually paralyzed in their inability to effectively defend themselves and their reputations. While McCarthy was touring the country delivering his poisonous speeches, his two Senate aides, Roy Cohn and G. David Schine, were touring U.S. government libraries around the world, demanding that books by “subversive” authors be purged from the shelves.

McCarthy’s tactics outraged all decent people, and I wondered if the Republican Party, which I strongly supported, would disassociate itself from him even as his power remained largely unchecked.

I was not thinking of Sen. McCarthy as I watched Eisenhower rise to deliver what were expected to be his brief remarks. But Eisenhower decided to add something more substantive.

“Don’t join the book burners,” he said. “Don’t think you are going to conceal faults by concealing evidence that they ever existed. Don’t be afraid to go in your library and read every book, as long as any document does not offend our own ideas of decency. That should be the only censorship.”

The president’s comments, blandly delivered, immediately became headlines. Few doubted that Eisenhower had McCarthy in his sights that day at Dartmouth. “Blast by Ike at Book Curb Stirs Capital,” declared United Press. The New York Daily News used one of its pithy, inimitable headlines: “Ike Lambastes Book Burners; He Mean Joe?” The Nassau Daily Review-Star on Long Island called it “Ike’s Best Speech” because he “appealed to the moral courage of Americans to live as Americans.”

Eisenhower’s attempt to explain several days later that he “never makes personal attacks” on others was unpersuasive. The speech that my classmates and I had just witnessed was the first salvo in a behind-the-scenes battle between McCarthy and the White House, one that culminated a year later in McCarthy’s condemnation by a formal resolution of the Senate.

Eisenhower had no intention of delivering a substantive speech, and his decision to extemporize the book-burning remarks was stunning. A new and untried president spoke strongly about an important and controversial public issue without consulting his advisors to determine whether such an action would be politically prudent.

College archives provide clues as to how and why Eisenhower decided to make his remarks. On the platform in front of Baker Library that day, as the long opening procession of faculty and members of our graduating class slowly came to an end, Eisenhower sat down near the large pine stump that still serves as the Commencement lectern. To his right were other degree recipients: Lester Pearson, the Canadian minister for external affairs who in future years would win the Nobel Peace Prize and become his country’s prime minister; Joseph Proskauer, a highly respected New York appellate judge; and John McCloy, who had served immediately after World War II as U.S. high commissioner for Germany. The men were talking informally.

Richard Morin, Dartmouth’s librarian, was seated just behind them, and he wrote afterward how Proskauer began an exchange with Eisenhower. Speaking loudly so as “to cover the distance between him and the President,” Proskauer remarked that he “was disturbed by the withdrawal of books from American libraries in Germany on grounds of a disapproval of their contents or their authors,” according to Morin. “The President said he didn’t believe that this kind of censorship was going on because Jack McCloy had told him not so long ago that American libraries in Germany contained books which made numerous critical references to him (the President). The President seemed amused by the presence of books critical of him, and certainly there was nothing in his reference to them that suggested the slightest disapproval of their being available in libraries.

“Proskauer greeted the President’s remark with an expression of skepticism but did not then contradict the President.…A moment later Proskauer turned back and said, ‘Mr. President, I think you are wrong about that.’ The President said, ‘Well, that could be,’ or some quite similar phrase. Proskauer then spoke of a book by Vera Micheles Dean, which among others had been withdrawn from U.S. libraries in Germany, and stated his admiration of Mrs. Dean’s writings. He made it clear that Mr. McCloy confirmed the book withdrawal activities, which have recently been reported in the press. The President listened attentively to Proskauer’s comments and then said, ‘But who is withdrawing the books?’ Proskauer replied, ‘The State Department.’ ”

After that exchange, Proskauer and McCloy were astonished as well as delighted to hear the remarks that Eisenhower delivered, according to Morin, and Proskauer expressed gratitude to the president.

If there were doubts about the spontaneity of Eisenhower’s remarks, Dickey cleared up any questions about it in a memorandum he prepared after he delivered remarks at Proskauer’s 90th birthday dinner in New York City in 1967. In his remarks Dickey briefly recounted the 1953 Commencement story as Morin had recorded it. After the dinner Proskauer amplified what had transpired on the platform.

According to Dickey’s memo, “Proskauer said it was correct that he had raised the matter with President Eisenhower as we were sitting on the platform while the senior class marched in.…He said the president had finally accepted the validity of his assertions and remarked that he was going to be making a speech elsewhere later that day and he might be able to say something to show his disapproval of book burning. Proskauer told me that he immediately said, ‘Mr. President, if you are going to speak out against book burning, the time to do it is now here at Dartmouth in front of this library.’ ”

A few minutes after the discussion on the platform, the president rose to speak. Weighing on his mind, most likely, was a letter he had received a few days earlier from Philip Reed, chairman of General Electric, who had written to his longtime friend about effects of McCarthyism that Reed had observed during a recent trip to Europe, and a New York Times column by James Reston decrying book banning in U.S. libraries abroad.

The book-burning remarks changed policy. On June 15, U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles publicly stated that only 11 books had been burned out of the

2 million books in 285 U.S. overseas libraries. On June 22, however, The New York Times, having surveyed libraries in 20 capitals, reported that, although they had not actually been burned, hundreds of books by at least 40 authors had been removed from U.S. overseas libraries. Two weeks later Anthony Leviero of the Times reported that “10 different directives had been issued in the effort to clarify the book issue,” and that the State Department’s “indecisive” policy was “strongly disappointing at the White House.” The president publicly commented that he would not have discarded Dashiell Hammett’s mystery stories.

On July 8, at Eisenhower’s direction, a new State Department order was issued, “basing the acceptability of a book more on its contents than on its author’s political affiliations or reticence about them.” It was hoped the program would now serve its original purpose to educate other people about America—including its flaws.

By August Congress established the U.S. Information Agency as an office independent of the State Department reporting directly to the White House. Within a year Sen. Ralph Flanders (R-Vt.) introduced a resolution censuring McCarthy that the Senate adopted before the end of 1954. McCarthy, now shunned by his colleagues, had lost his political power. Within three years he was dead.

Richard C. Cahn was undergraduate editor of DAM in 1952-53, graduated from Yale Law School in 1956 and served as a trial attorney in the Eisenhower Justice Department. He lives with his wife, Vivian, in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, where they raised their four children.