Fighters to the End

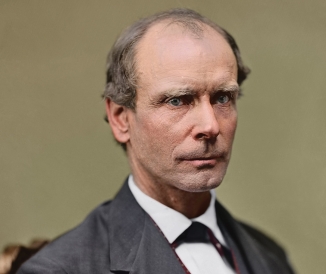

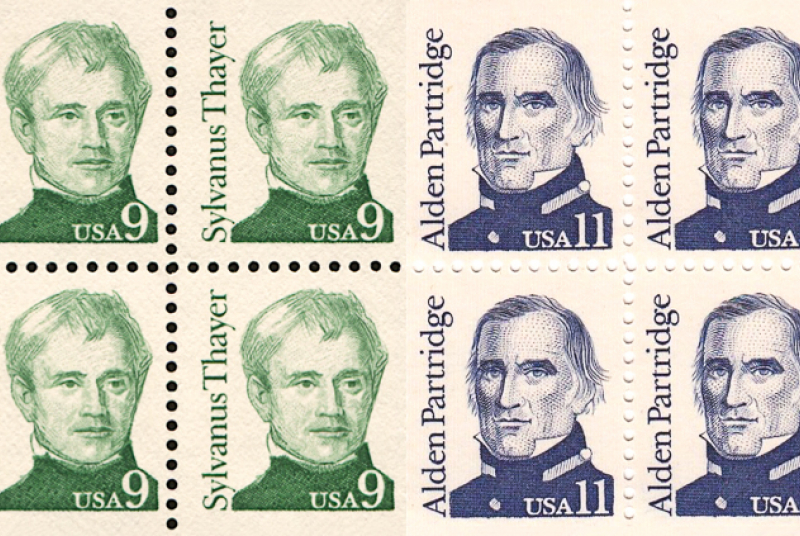

Long before Dartmouth had any formal affiliation with the armed services, the College admitted two men who went on to become highly influential educators in American military history. Sylvanus Thayer, creator of the professional and meritocratic American military tradition, is not only the namesake of Dartmouth’s school of engineering (now celebrating its 150th anniversary), but he is also a legend on the West Point campus, where his statue presides over the main parade ground. Alden Partridge, an advocate of a reserve force of well-trained citizen soldiers, is equally revered at Norwich University in Northfield, Vermont.

They held mutual interests in mathematics, engineering and physical discipline and established programs that continue to turn out a large number of the country’s U.S. Army officers. But when President James Monroe ordered Thayer to replace Partridge at the helm of West Point, he set off a bitter rivalry that lasted through their dying days.

Partridge, who grew up on his parents’ farm in Norwich, Vermont, came from a family with a distinguished history of military service in the American Revolution. After three years at Dartmouth he was appointed by President Thomas Jefferson to join the corps of cadets at West Point, which had been founded in 1801. From 1805 until 1817 he served as a student, professor and superintendent. He was a vigorous and active administrator during a period when the academy received scant government support. Some faculty members, however, accused Partridge of being disorganized and lenient.

President James Madison, sensing a need to improve the educational training of the American military, in 1815 dispatched Major Thayer to tour Europe for two years. His mission was to observe military training and fortifications, especially in France at the elite Ecole Polytechnique, and gather books for a West Point library.

Thayer, who was born in Braintree, Massachusetts, spent his formative childhood years at his uncle’s farm in Washington, New Hampshire. At Dartmouth he graduated as class valedictorian. He went on to West Point and entered the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers after a year. Serving in the War of 1812, he observed what he felt was mediocrity among the officer corps. This deeply affected Thayer and led him to become a proponent of a professional and elite officer corps that would be trained and held to the highest standards.

Thayer returned to the United States in 1817, as West Point roiled with rancor over its leader. The new president decided to replace Partridge. Thayer got the job.

The appointment fostered a searing resentment in Capt. Partridge. He resisted his dismissal and “forcibly assumed command,” according to Thayer. After Partridge was threatened with a court martial, he resigned his post and his commission and swore revenge upon Thayer. “Should I live to be seventy this subject shall never within that time be abandoned unless justice be done,” wrote Partridge.

As superintendent Thayer made his views clear. “Gentlemen must learn…it is only their province to listen and obey,” he told cadets. He issued 200 new regulations that dictated every aspect of a cadet’s daily life. He instituted a strict merit ranking system (that continues today) and overhauled the quality and rigor of the curriculum. “Favoritism is now banished and the road opened for the advancement of merit, whether it be found in the son of a beggar or a king,” wrote one professor. West Point became an elite school and national institution where performance, discipline and excellence were paramount.

Partridge, while West Point superintendent, had proposed a plan of expanding the military academy and creating at least two additional locations. He foresaw the need to create a reserve of well-trained militia officers who would be available in an emergency for “officering any additional force that might be necessary,” although he resisted the concept of a wholly professional elite officer corps. Stymied in his efforts at West Point, in 1819 Partridge returned to Norwich to establish the “American Literary, Scientific, and Military Academy.” (It moved to Northfield in the 1860s). In time, using Norwich as a model and inspiration, Partridge helped establish 18 private military academies in New Hampshire, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware. His influence extended to schools throughout the country in the West and South. His support and guidance were vital in helping to support the creation of the Virginia Military Institute in 1839 and the Citadel in 1842. Partridge’s ideas influenced Vermont Sen. Justin Morrill and ultimately led to the creation of ROTC.

Partridge expounded a curriculum he labeled the “American System” in which military education was an “appendage” to civil education. He wanted to inculcate the ideal of the citizen soldier in the model of George Washington and Andrew Jackson. His curriculum was designed to produce a “well organized and well-disciplined militia, which the Founding Fathers…declared necessary for a free state,” he wrote. He wanted to “render a mercenary army unnecessary.”

Physical fitness and outdoor training were an integral aspect of Partridge’s educational philosophy. He was an avid outdoorsman, leading strenuous hikes in the Green and White mountains. Dartmouth students joined cadets from Norwich on epic expeditions to climb Mount Washington, including the first ascent of the newly cut Crawford Path trail in 1821. These arduous exertions were some of the first organized by an American to incorporate outdoor education into a legitimate curriculum. Partridge anticipated Outward Bound by more than a century.

At West Point Thayer earned accolades as he implemented his vision of an elite professional officer corps. “The Academy has been placed in a state of the most perfect organization & efficiency under his administration,” wrote one of his supervisors in 1823. A board of visitors was established, composed of dignitaries including famous politicians Sam Houston and DeWitt Clinton, esteemed educators such as Dartmouth classmate George Ticknor, class of 1807, and Horace Mann, who marveled that “the length of course and the severity of studies pursued…have rarely, if ever, seen anything that equaled either the excellence of the teaching or the proficiency of the taught.”

However, the tone of the nation in the late 1820s was becoming more populist, and Thayer’s strict rule had created some resentment—cadets, some of whom staged a rebellion in 1818, called him “His Sylvanic Majesty.” President Andrew Jackson, who had declared in 1825 that West Point was “the best school in the world,” began to criticize Thayer’s strict administration and overturn his rulings, thundering, “Sylvanus Thayer is a tyrant! The autocrat of all Russia couldn’t exercise more power.” Jackson’s view was colored by many, including his nephew Andrew Donelson, a former disgruntled cadet and later his private secretary, but a critical influence was Thayer’s nemesis Alden Partridge.

In 1830 Partridge published an anonymous pamphlet, “The Military Academy at West Point Unmasked, or Corruption and Military Despotism Exposed.” He vilified Thayer’s leadership and accused him of creating a monarchical establishment that aimed to “build up a privileged order of the very worst classes, a military aristocracy.” The pamphlet reinforced Jackson’s concerns, and the relationship between Thayer and Jackson soured. Unlike Partridge, who had violently resisted his own ouster, Thayer elected to discreetly move on. He quietly resigned his post in 1833 and joined the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, never to return to West Point.

As Thayer entered his final years, he turned to philanthropy. He had earned substantial commissions for his work overseeing construction projects and had accumulated a large fortune. In 1867 he wrote to Dartmouth President Asa Dodge Smith, class of 1830, and offered “to place in the hands of trustees the sum of thirty thousand dollars, the income derived therefrom to be applied to the establishment and maintenance of a department or school of architecture and civil engineering connected with Dartmouth College, the institution on which I was educated and in the prosperity of which as my alma mater I feel the deepest interest.” After extensive deliberations with Smith and faculty, Thayer increased his gift to $60,000 and the Thayer School of Civil Engineering opened in 1871.

Thayer died in 1872 and in his will, which included an additional gift of $12,000 for Dartmouth, he forth the blueprint for his vision of an academy in Braintree. His total gift for the creation of Thayer Academy exceeded $300,000, which was an enormous sum that endowed his school more generously than most other private academies and even colleges in New England. The Thayer Public Library, endowed with a gift of more than $20,000 in 1870, and Thayer Academy still honor his memory in Braintree.

Partridge died in 1854 but his influence, too, lives on. Norwich University in 1915 was the site of a speech by Major Gen. Leonard Wood, Army chief of staff, that outlined what would become a system of reserve officer enlistment and training. Legislation establishing ROTC, based on the ideas and experience of Partridge and Norwich, was passed in 1916.

Although the successful ROTC program overseen by instructors from Norwich University at Dartmouth continues to exemplify a blend of professionalism and democratic service that both Thayer and Partridge could endorse, the two men never made peace with each other.

William Clark is a senior managing director of leadership giving at Dartmouth. Hank Erbe ’84 and professors Gary Lord of Norwich University and Samuel Watson of West Point assisted with research for this story