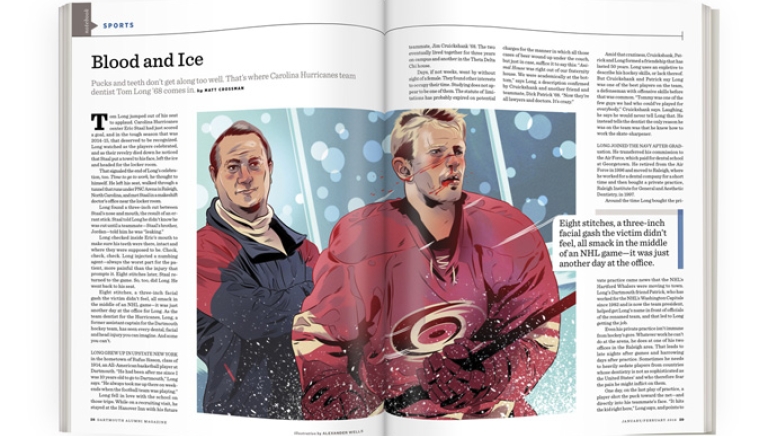

Tom Long jumped out of his seat to applaud. Carolina Hurricanes center Eric Staal had just scored a goal, and in the tough season that was 2014-15, that deserved to be recognized. Long watched as the players celebrated, and as their revelry died down he noticed that Staal put a towel to his face, left the ice and headed for the locker room.

That signaled the end of Long’s celebration, too. Time to go to work, he thought to himself. He left his seat, walked through a tunnel that runs under PNC Arena in Raleigh, North Carolina, and met Staal in a makeshift doctor’s office near the locker room.

Long found a three-inch cut between Staal’s nose and mouth, the result of an errant stick. Staal told Long he didn’t know he was cut until a teammate—Staal’s brother, Jordan—told him he was “leaking.”

Long checked inside Eric’s mouth to make sure his teeth were there, intact and where they were supposed to be. Check, check, check. Long injected a numbing agent—always the worst part for the patient, more painful than the injury that prompts it. Eight stitches later, Staal returned to the game. So, too, did Long. He went back to his seat.

Eight stitches, a three-inch facial gash the victim didn’t feel, all smack in the middle of an NHL game—it was just another day at the office for Long. As the team dentist for the Hurricanes, Long, a former assistant captain for the Dartmouth hockey team, has seen every dental, facial and head injury you can imagine. And some you can’t.

Long grew up in upstate New York in the hometown of Rufus Sisson, class of 1914, an All-American basketball player at Dartmouth. “He had been after me since I was 10 years old to go to Dartmouth,” Long says. “He always took me up there on weekends when the football team was playing.”

Long fell in love with the school on those trips. While on a recruiting visit, he stayed at the Hanover Inn with his future teammate, Jim Cruickshank ’68. The two eventually lived together for three years on campus and another in the Theta Delta Chi house.

Days, if not weeks, went by without sight of a female. They found other interests to occupy their time. Studying does not appear to be one of them. The statute of limitations has probably expired on potential charges for the manner in which all those cases of beer wound up under the couch, but just in case, suffice it to say this: “Animal House was right out of our fraternity house. We were academically at the bottom,” says Long, a description confirmed by Cruickshank and another friend and teammate, Dick Patrick ’68. “Now they’re all lawyers and doctors. It’s crazy.”

Amid that craziness, Cruickshank, Patrick and Long formed a friendship that has lasted 50 years. Long uses an expletive to describe his hockey skills, or lack thereof. But Cruickshank and Patrick say Long was one of the best players on the team, a defenseman with offensive skills before that was common. “Tommy was one of the few guys we had who could’ve played for everybody,” Cruickshank says. Laughing, he says he would never tell Long that. He instead tells the dentist the only reason he was on the team was that he knew how to work the skate-sharpener.

Long joined the Navy after graduation. He transferred his commission to the Air Force, which paid for dental school at Georgetown. He retired from the Air Force in 1996 and moved to Raleigh, where he worked for a dental company for a short time and then bought a private practice, Raleigh Institute for General and Aesthetic Dentistry, in 1997.

Around the time Long bought the private practice came news that the NHL’s Hartford Whalers were moving to town. Long’s Dartmouth friend Patrick, who has worked for the NHL’s Washington Capitals since 1982 and is now the team president, helped get Long’s name in front of officials of the renamed team, and that led to Long getting the job.

Even his private practice isn’t immune from hockey’s gore. Whatever work he can’t do at the arena, he does at one of his two offices in the Raleigh area. That leads to late nights after games and harrowing days after practice. Sometimes he needs to heavily sedate players from countries whose dentistry is not as sophisticated as the United States’ and who therefore fear the pain he might inflict on them.

One day, on the last play of practice, a player shot the puck toward the net—and directly into his teammate’s face. “It hits the kid right here,” Long says, and points to his own perfectly straight front teeth. “He broke six, eight teeth. We were there for a couple hours putting him back together.”

Sitting in his seat during a game last year, Long chats easily with other fans sitting in the area. They’ve sat near each other for years and they all call him Doc. He estimates he has missed 10 games in 17 seasons, a sparkling attendance rate considering Long’s season tickets constitute his salary for being the team dentist. After he said that, he thought for a second. He looks a row back, where his wife, Shawn, is sitting.

“Does that sound right?” he asks.

She smiles. Broadly. Then she suggests the number is probably about five. She played college hockey and attends most of those games with him. His children— Shane (who played to the juniors level), Whitney, Brendan and Morgan—attend a lot of games, too.

Long always sits in the same spot: Seat 1, Row P, Section 108, on the third of the ice where the visiting team shoots twice. He likes to sit there because he can see the whole ice, and also because it allows quick access to the tunnel. That’s important for his midgame routine: During each intermission he walks from his seat to the locker room to see if anybody needs him. He and a partner alternate taking care of both teams playing. (NHL home teams provide medical care for away teams.)

Years ago he hustled over to the tunnel behind the team bench as blood dripped from a player’s face. Several of the player’s teeth were scattered on the ice behind him. Another player, Rod Brind’Amour, skated over to them and scooped them up with his stick. Brind’Amour glided toward Long and held up his stick, the teeth sitting on it like macabre hors d’oeuvres. “Do you need these, Doc?” Brind’Amour asked.

“No,” said Long. “I’m good.”

For most of his time with the team, Long encountered something brutal like that nearly every night. With rules changes and better equipment in the last few years, though, the need for his services has diminished. Now he sees something outrageous or grotesque “only” every third game or so.

For all the damaged teeth Long has seen, his own made it through decades of playing the game undamaged, which is not the same as untouched. “I got hit in the mouth a lot, but I never lost my teeth,” he says. He’s got a great smile, and he flashes it a lot. It’s too perfect to be true. “I got my teeth redone later on, after I got out of the military. I never liked my smile, all my life.”

Before he took the job with the Hurricanes, Long had seen more trauma than most dentists. In the Air Force he was stationed in Germany during the Cold War. “We didn’t know what the Russians were going to do. If they ever came across the Fulda Gap and decided they were going to attack, we’d never have enough doctors to take care of all the casualties,” he says. To prepare for that, non-surgeons such as Long sat in on surgeries and stitched patients up at the end.

So he was ready, at least a little, for lips that look like hamburger, broken jaws and snaggle-toothed smiles. Morning skates, afternoon practices, night games—all are likely to result in visits to Long, with injuries often gruesome, even life-threatening on rare occasions.

Mark Recchi, then with the Philadelphia Flyers, skated to the bench in Raleigh one night to find his teammates staring at him. They were appalled. He wondered what the big deal was. They told him blood was pouring out of his neck and chin.

When Recchi arrived in the locker room, Long put his hand over Recchi’s neck and chin to try to stop the bleeding. When it wouldn’t stop, Long pulled back his hand to take a closer look. Recchi’s neck was filleted open, and Long could see his carotid artery pulsing. Long instinctively looked for a hemostat to clamp the artery, just in case, while trying to look like nothing was wrong. “We didn’t really say, ‘Oh s---, you’re about to die.’ But we were thinking, ‘I hope to hell that thing’s okay,’ ” Long says.

Recchi, now a coach in Pittsburgh, credits Long with keeping his cool. “He said, ‘Oh, this is really close, a millimeter away from your artery,’ or whatever. I was just like, ‘Oh, s---,’ ” Recchi says. “He started talking, and relaxed me and started working on it.”

Recchi and Long talked for 90 minutes while the team doctor stitched Recchi back together. Later, Recchi was traded to Carolina. When Recchi arrived to meet his new team, he shook hands with the coach before walking by the players to shake hands with Long and the other doctor and thank them for the work they did the night he almost bled to death. “He was awesome,” Recchi says. “The guys love him.”

Matt Crossman is a freelance writer who lives in Charlotte, North Carolina.