Her images portray an eerily static world. Only traces of human presence appear in her landscapes: tire tracks in the sand, a signpost on a beach, the lights of a faraway town on the distant shore of a moonlit bay. Virginia Beahan, who teaches photography at Dartmouth and whose images are in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, tries to capture something beyond the fleetingness of the moment. “I think in earth time,” she says. “I ultimately see us humans in the context of the orbit of the earth, the phases of the moon and the changing of the seasons.”

Recently there has been a lot of interest in Beahan’s work: After she published her second monograph, Cuba: Singing with Bright Tears (Pond Press, 2009), Beahan had a solo exhibition at Joseph Bellows Gallery in La Jolla, California, and participated in a group exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Her work is currently displayed at the Getty in a group exhibition, “A Revolutionary Project: Cuba from Walker Evans to Now,” which runs through October 2.

Beahan says she has been captivated by Cuba since her first visit in 2001, when she was struck by the way its history, politics and culture were “inscribed on the land.”

Although Beahan photographs many landscapes, Judy Keller, senior curator of photographs at the Getty, emphasizes that Beahan “is not simply interested in the scenery and how to make a beautiful composition out of that. She’s interested in what has taken place at a particular site and in the marks that people have made on the landscape.” Unlike digital photographers who take multiple shots in a short time, Beahan often spends days planning one photograph, for which she takes no more than one or two exposures. “This may almost seem like an archaic way of working,” says Keller, “but the process determines the product, and she’s getting exactly the result she’s after.”

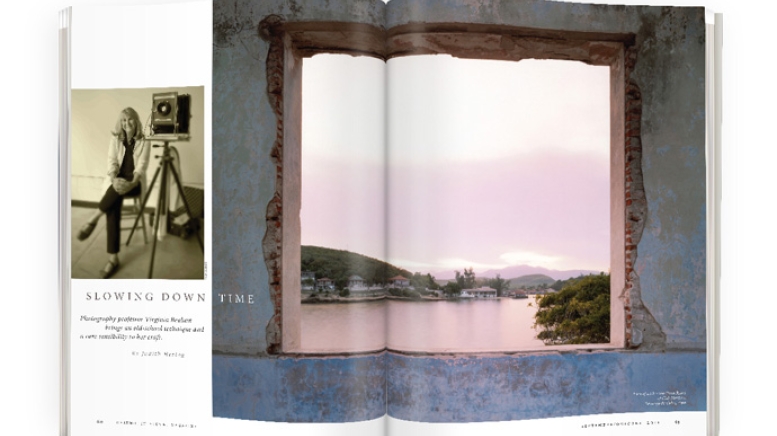

Beahan uses an old-school, large-format Deardorff camera that is the antithesis of snapshot photography. The large instrument, which folds down to the size of a briefcase, must be set up on a tripod, leveled, fitted with the appropriate lens and manually focused. A fresh 8-by-10 negative sheet needs to be inserted for every exposure. Because Beahan favors low-light conditions that require extremely long exposures—sometimes hours—the result is true slow-motion photography: moving elements, such as streaming water or swaying tree branches, are often blurred, and in some of the longer exposures, people who walk through the frame are not captured because their presence is too fleeting to leave a trace.

“This camera reaches back into time,” Beahan says about her Deardorff. “It’s similar to the very first cameras that were invented, and I like the relationship it gives me with the history of photography. If I have to, I can fit this whole camera into a backpack.” She sighs, however, at the memory of hiking up mountains in Iceland with about 50 pounds of equipment on her back. “This is a camera of substance,” she declares. “I love the wooden body, the large lens, the heavy glass.” Beahan also likes to point out that although digital images are ephemeral computer code that becomes inaccessible as technologies change, photo negatives are real, physical objects. She has little interest in digital image doctoring. “I’m sometimes asked if my pictures were manipulated,” she says, “which they are not, because the work I’ve been doing depends on the idea that this is the world and not some fantasy in my mind.”

Beahan’s blue eyes shine with a passion for the world that is expressed not only in her photographs, but also in the beauty surrounding her. She lives with her husband, Michael, in a 200-year-old restored farmhouse in Lyme, New Hampshire, amid a landscape of ancient stone walls, terraced gardens, meadows and forests.

“Photography has made me look more carefully at the world,” says Beahan. “Sometimes I feel I get a headache from looking so hard. But I can’t look at things without appreciating the colors, the way the light falls, or even other things I’m reminded of.”

As a teacher, she tries to instill this intensity of seeing in her students. “At the beginning of a term she’d have a group of students who took pictures of things they thought were interesting, and by the end she had a group of students making interesting photographs. I still don’t know how she did it,” says Jordan Benke ’02, a studio art major who worked for two terms as a teaching assistant in Beahan’s photography class and now works as an art production manager. The trick, says Beahan, is simply to look. “Photography really trains the eye and the mind,” she says. “It leads to a more palpable appreciation for the visual world, and the visual world is gorgeous, isn’t it?”

Beahan received her first camera, a Kodak Brownie, at 7, and although many of her family members were amateur photographers, Beahan was no photography prodigy. As an undergraduate majoring in English literature at Penn State she took a few classes in the medium, but it wasn’t until her mid-30s that she realized her passion. She had already worked for several years as a high school English teacher by then. After the birth of her daughter in 1977, Beahan started auditing classes at Princeton with photographer Emmet Gowin, who hired her as a teaching assistant the following year and encouraged her interest. Gowin, who since has morphed from teacher into friend and colleague, recalls a telling interaction with Beahan when she was his teaching assistant. He showed her some prints of his first experiments with landscape photography to which she responded that although such landscapes had always seemed impersonal to her, these images carried a lot of emotion. “She may not even remember that conversation,” says Gowin, “but in retrospect it strikes me that she was in fact commenting on her own future work.”

In 1984 Beahan completed the M.F.A. program in photography at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University, where she was the oldest student. After graduation Beahan taught photography at Columbia, Bard College, Wellesley, Massachusetts College of Art and Design and, since 2001, Dartmouth. She has received Mellon Foundation and Guggenheim grants to pursue photo projects all over the world.

Beahan also chronicled the last years of her mother’s life, as she was succumbing to dementia—a series that appeared earlier this year at the Smithsonian’s “Close to Home” exhibit. “She couldn’t remember the past or think about the future,” Beahan says about her mother, “but she could be very much in the moment. That’s what these pictures were about: capturing these passing moments of intense beauty, a beauty we’re usually not paying attention to because we’re too busy.”

Beahan’s next project reaches back to her interest in literature. She plans to return to Cuba, which she has visited regularly between teaching terms, to photograph places that played a role in the life of Ernest Hemingway. “I’m interested in a revisualization of his Cuba, using my artistic imagination to revisit the place that Hemingway fell in love with,” says Beahan. “I envision it as a coming together of past and present through his artwork and my artwork.”

In the meantime, Beahan is rereading Hemingway, whose books and biographies are piled up in her living room. But she won’t be staying indoors for long. “My happiest moments are when I’m outside somewhere in the middle of nowhere, waiting for the light to change to take a picture,” Beahan says.

Judith Hertog is a regular contributor to DAM. She lives in Norwich, Vermont.